Kroger is Complex

DISRUPTION emerges from particulars of time and space. The character of disruption reflects innate complexity and unpredictable convergence of multiple variables.

Wealth attracts. Wants and needs pull. As populations increase, so do varied preferences. Individuality spawns diversity. Proliferating demand stimulates diversification of supply.

Just-in-Time typically involves a deliberate fracturing of space in order to better measure and manage duration. Organizations that are most effective at reducing the time-line tend to focus on discreet aspects of space and/or time, developing unique abilities to bend space-time to their specific intention.

In the last thirty years – especially in the last fifteen years – this has often resulted in the disaggregation of functional capabilities. Conglomerates have spun apart. Vertical integration has been constrained or abandoned. Specialization is rewarded. The linear is becoming networked.

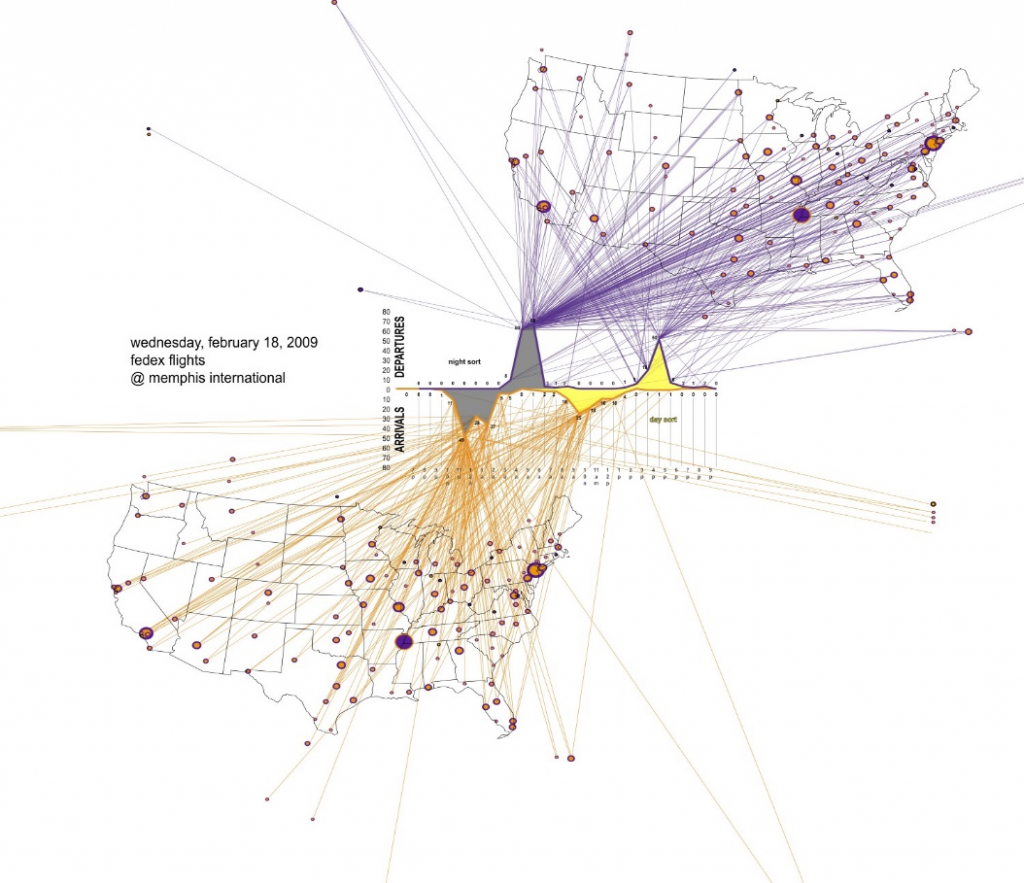

In the late 1970s and 1980s FedEx transformed the cargo industry by specializing on end-to-end transport of high-value, small component packages. Since then FedEx has thrived by deploying its signal-rich, air-oriented hub-and-spoke model to a whole range of products and markets. Along the way the company has evolved from a tightly-focused niche player to a wide-ranging integrated category leader. But it continues to organize around different niches, often applying self-managing business units to different niche needs. FedEx has tried to maintain a decentralized culture even as it deploys shared systems and processes.

In 1993 Peter Drucker, a leading scholar of business management, wrote, innovation “requires systematic effort, and a high degree of organization. But it also requires both decentralization and diversity, that is, the opposite of central planning and organization.” Structural integration can accommodate decentralization and diversity, but – over time – there is a growing temptation to second-guess and overturn local decisions to impose greater consistency and supposed efficiency.

Foolish consistency inappropriate to conditions and purposes begs for innovation.

To escape the hobgoblins of foolish consistency, innovation must be constant and extend from the micro to the macro. In their book, If We Can Put a Man on the Moon, William Eggers and John O’Leary write:

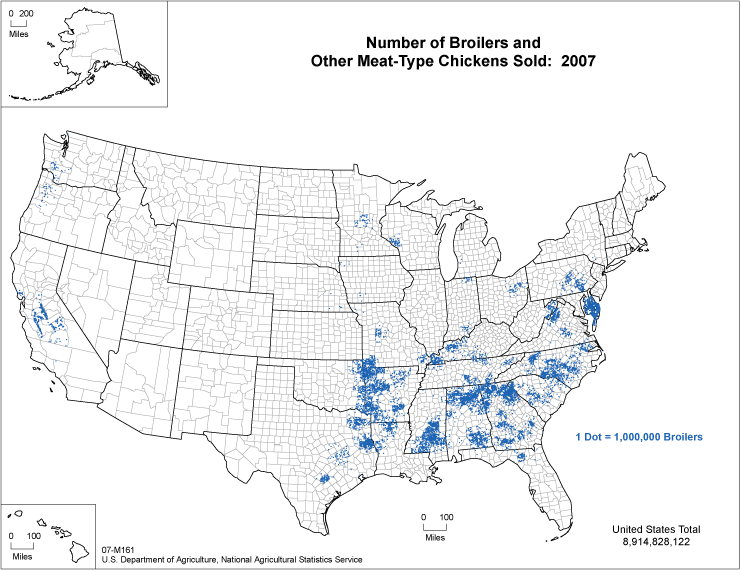

Consider: Who is in charge of getting the right number of chickens to Manhattan every day? After all, few chickens live there, but a lot of chickens get eaten there. The typical Manhattanite downs about sixty pounds of chicken a year, in every imaginable form, from chicken chow mein to chicken nuggets, from organic chicken to those little cubes that float in your can of chicken soup. Untold thousands of people participate in providing for Manhattan’s ever-changing chicken needs, from truck drivers to restaurant owners, from grocery store managers to Arkansas chicken farmers. Who is in charge? Who makes sure that New York City winds up with the right amount of the right kind of chicken?

The answer is: No one. The chaos of the uncontrolled buying and selling of the market produces an orderly pattern of exchanges that coordinates the activities of independent yet interdependent participants. The result, without any central planning, is an adaptable and ever-changing arrangement that generally meets the needs of Manhattan’s chicken eating public. The government provides certain oversight and context for the market. The U.S. Department of Agriculture watches over chicken farms and the city’s Board of Health licenses and inspects restaurants. Chickens are hauled over public roads and contract disputes between chicken farmers and truckers are resolved in public courts. But when it comes to the essence of the chicken delivery system—how much chicken, of what kind, at what price—it is the invisible workings of supply and demand that align the productive activities of a loose network of thousands of people (and companies) in making sure New Yorkers get their chicken potpie, chicken vindaloo, and extra-spicy buffalo chicken wings.

Map above based on US Department of Agriculture data

Order emerges from chaos. From millions of individual pull signals heard or half-heard, eggs are brooded, chicks are fed, broilers are processed, refrigerated trailers are chilled, trucks are fueled, drivers are employed and chickens — kosher, whole and cut, halal, live or packaged, skinned and not, frozen, and more – are delivered to diverse populations across a continent.

Many high-demand supply chains increasingly behave as complex adaptive systems. More people with greater buying power generate increasing demand diversity. More frequent and varied “pulls” require greater frequency and agility of supply. With enough signal clarity the system self-organizes around a set of persistent values that determine outcomes but resist full prediction.

Supply Chains and other networks are complex adaptive systems when they demonstrate the following characteristics:

- Large Number of Elements: The number of elements and interactions among elements is sufficiently large that conventional descriptions are not only impractical, but cease to assist in understanding the system. The Kroger supply chain involves more than 13,000 SKUs sourced globally. The firm attempts to track up to 150 attributes for each product. It delivers to over 2600 stores in 34 states and the District of Columbia. The grocery supply chain includes a multiple of elements beyond the Kroger supply chain. The food supply chain is a multiple of the grocery supply chain.

- Beginnings matter: Each complex adaptive system has a history. Each system evolves and past experience influences present behavior. Kroger has a national footprint and is a market-leader in cities from Los Angeles to Atlanta to Houston to Seattle. The firm was founded, and is headquartered, in Cincinnati, Ohio. It continues to be concentrated in the Midwest and Middle South. Kroger allows its Los Angeles operations – branded as Ralphs and Food4Less – significant independence, reflecting the different history of this local sub-system.

- Mostly proximate interactions: Interactions are primarily but not exclusively with a comparatively few direct connections and the nature of the influence is modulated. Kroger private label products–including bakery, dairy, and meat–constitute about 25 percent of sales or nearly $20 billion per year. The company self-manufactures roughly 40 percent of its private label products, procuring raw materials directly from hundreds of vendors. But for nearly 90 percent of its sales Kroger has no interaction with the tier of suppliers behind the finished product. Most supply chain operators have no visibility into their second tier of suppliers, making decisions on the basis of the limited information available to them.

- Rich Interactivity: Any element or sub-system is affected by and affects several other elements or sub-systems. Some of Kroger’s toughest competitors – e.g. Walmart and Costco – are willing to lose money on food in order to drive traffic and purchases for higher-margin products. Kroger has been able to remain price competitive by developing its robust private-label, by aggressively negotiating volume discounts from suppliers, and by using fuel discounts to drive traffic, among other strategies.

- Non-linear interactivity: Small changes in inputs, physical interactions or other relationships can prompt significant changes in output. Over the last two years Kroger has cut prices on selected products. For example, in April 2015 price reductions in Northern Ohio included: organic broccoli at $1.79 a pound falling from a $2.69 per pound, mini-carrots at 99 cents from $1.49, pork ribs at $2.99 a pound from $4.99, and Heritage Farm chicken breast at $1.99 a pound from $2.99. Salmon was cut one dollar to $6.99 a pound, mangoes were cut to 99 cents each from three-for-$5, and cucumbers dropped a dime to 49 cents. With these and other price-reductions, the company chose to narrow its gross profit margin– 26 percent in 2003 to just over 20 percent more recently – in order to drive a doubling of sales volume over the last decade.

- Recurrent Feedback: Any interaction can feedback onto itself directly or after intervening stages. In supply chains different perceptions of feedback at different tiers of the supply chain can produce what is called a “bull whip effect”. Between 2009 and mid-2014 dairy farmers in Northern New York and New England struggled to expand production to supply the exploding Greek Yogurt market. But by the close of 2014 milk prices in the region had fallen by nearly half as supply shot-past demand.

- Indefinite Boundaries: Systems are open, constantly fluctuating, and it can be difficult or impossible to define system boundaries. Lara Sowinksi writes in Food Logistics, “the food chain is becoming progressively more globalized for most countries around the world. This globalization has created a range of opportunities and risks… A far reaching and more complex supply chain is prone to risks brought about by regulatory and non-tariff barriers, disruptions due to natural disaster, political upheaval and economic instability, rising oil prices and its effect on food production and transportation, and the dynamic and unrelenting variations in consumer demands and desires.”

- Constant Disequilibrium: Complex systems do not achieve equilibrium conditions. There is a constant flow of energy that maintains the system’s organization. Here’s how Kroger describes its environment: The operating environment for the food retailing industry continues to be characterized by intense price competition, aggressive expansion, increasing fragmentation of retail and online formats, entry of non-traditional competitors and market consolidation… We could also encounter unforeseen transaction and integration-related costs or other circumstances such as unforeseen liabilities or other issues. Many of these potential circumstances are outside of our control and any of them could result in increased costs, decreased revenue, decreased synergies and the diversion of management time and attention. If we are unable to achieve our objectives within the anticipated time frame, or at all, the expected benefits may not be realized fully or at all, or may take longer to realize than expected, which could have an adverse effect on our business, financial condition and results of operations, or cash flows. (SEC, Kroger Form 10K, March 2015)

Delivering the right number of chickens to New York at the right time is a daunting challenge. Delivering chicken and breakfast cereal and flavored beverages and yogurt and 13,000 other products to thousands of neighborhoods in competition with others trying to do something very similar for many of the same customers, with minimal waste, and maximum revenue: That is complex.

Post-Capitalist Society by Peter Drucker, 1993

Complexity and Postmodernism by Paul Cilliers, 1998

The Kroger Factbook, 2014

In Southern California Kroger operates under the Ralphs banner (among others). Below is a photorealist painting by Robert Cottingham currently in the collection of the Milwaukee Art Museum

Complex systems can feature characteristics that do not change if scales of length, energy, or other variables, are multiplied by a common factor. This aspect of dynamics and dilation is simulated by R.M. Dimeo:

The time is come, the day draweth near: let not the buyer rejoice, nor the seller mourn: for wrath is upon all the multitude thereof. For the seller shall not return to that which is sold, although they were yet alive: for the vision is touching the whole multitude thereof, which shall not return…

Prophecy of Ezekiel, Chapter 7, Verses 12-14

Kroger is Complex was written by Philip J. Palin, September 2015