Residents of the United States are the most high volume, high velocity consumers in the world. China’s factories are the most high volume, high velocity suppliers in the world. Demand and supply are engaged in an increasingly serious spat with already volatile outcomes.

The Financial Times reports, “US Treasury secretary Scott Bessent has accused China of trying to hurt the world’s economy after Beijing imposed sweeping export controls on rare earths and critical minerals, hitting global supply chains… Maybe there is some Leninist business model where hurting your customers is a good idea, but they are the largest supplier to the world,” he added. “If they want to slow down the global economy, they will be hurt the most.”

President Trump wants the United States to make more stuff again. He wants to recover US manufacturing capacity and jobs — especially related to producing goods perceived as fundamental to national security.

Trump administration policy and practice can be framed by three goals:

Discourage imports. Tariffs complicate and constrain supply by increasing both direct and indirect costs — eventually prompting increased prices, reduced import sales, and more opportunity for domestic producers. For example, last week a major European maker of farm equipment “has been forced to pause exports of large equipment to the US because of “alarming” and little-known new tariffs that are hitting hundreds of products” (here).

Encourage domestic manufacturing. Tax incentives, tariff waivers, and direct government investment are being deployed to support old and new industrial sectors perceived as fundamental to US economic and military essentials. Examples are here and here and here and here.

Generate federal government revenues: Tariffs are currently conceived as a sort of slotting fee that non-US suppliers pay for the privilege of accessing the US consumer. Tariffs support the two prior goals and generate much needed revenue for a high-deficit federal budget. Through the end of September more than $200 billion in tariff revenues were received (here and here).

China’s global exports grew over eight percent in September, while its flows to the United States declined by more than a quarter (here and here).

Euronews reports, “German exports to the United States have fallen for the fifth consecutive month, reaching their lowest level in nearly four years, as the impact of tariffs imposed by US President Donald Trump continues to reverberate across transatlantic trade” (more and more).

For the last five months postal parcel traffic to the United States has fallen by 70 percent (here and here).

There is demonstrable progress in discouraging imports. For all of 2025 US tariff revenues could easily triple 2024 totals (or more).

But increasing import costs and reducing import volumes are easier — and especially quicker — than rebuilding domestic manufacturing capacity (here) or opening more rare earth mines (here) or supporting industrial innovation (here and here and here). There is a real risk of reduced product availability and higher prices for a range of goods, prompting negative economic outcomes and related political feedback in the United States. There are also risks of trade retaliation impacting US exporters (here and here).

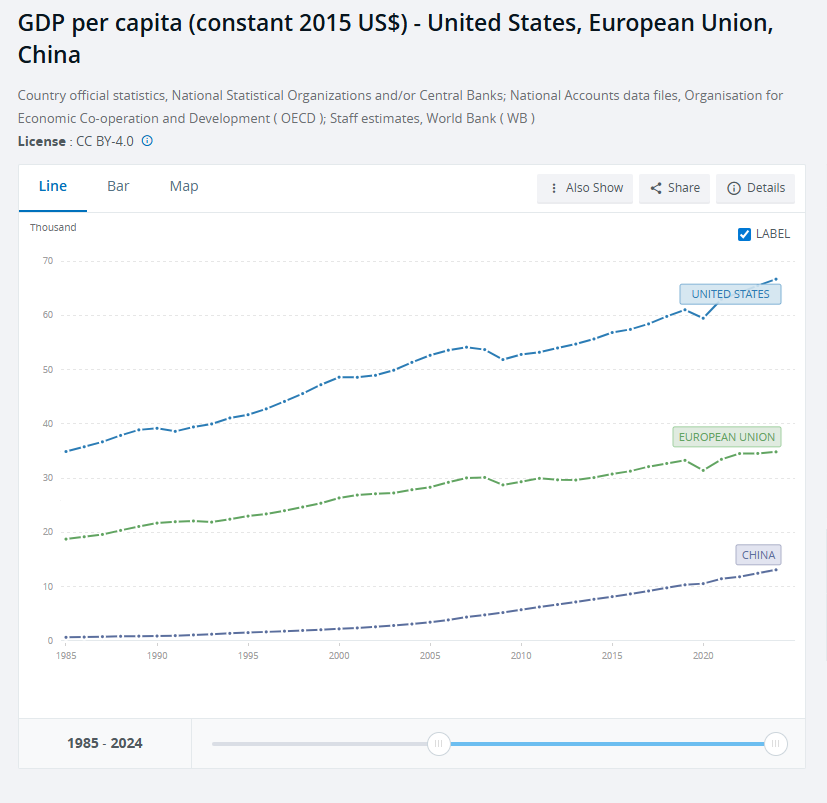

Meanwhile in China, economic growth has been sluggish — at least compared with the quarter-century before 2008 (here and chart below). An extended property crisis, deepening deflationary pressures, and reluctant consumer demand are mutually reinforcing and tough to undo. China’s manufacturing oversupply is a domestic as well as an international challenge (more).

The US is an extremely consumption-oriented economy. China is an extremely production-oriented economy. This could be — even has been — complementary. But the US and others increasingly perceive China to be economically predatory — and such predation could extend beyond economic competition. China perceives that the United States is being arbitrary and aggressive in restraining China’s competitive prowess and national achievements.

Starting in late September a month-long US-China detente deteriorated (here and here and here). Now China is threatening to cut-off global purchases of rare earths (more), while the US is threatening to cut-off China’s ability to sell much of anything in the United States (more). If either threat is consummated, the consequences will be tough to unwind. Several supply chains are being whip-sawed by these tensions, measures, counter-measures, and uncertainty. Trade flows have already been seriously disrupted. Friction is building.

The strategic value of anticipatory Supply Chain Resilience is certainly being demonstrated. But many of the best strategies will be existentially challenged if this tit-for-tat unfolds into mutually assured destruction of demand and supply networks shared over the last four decades.