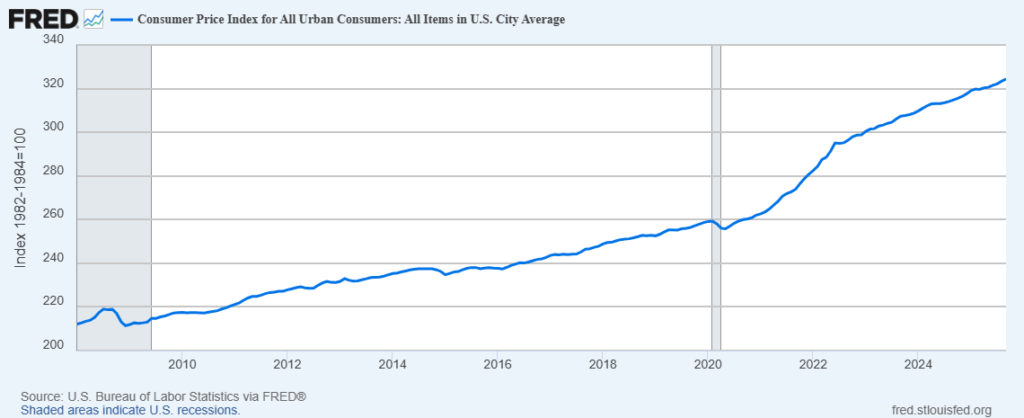

According to the Bureau for Labor Statistics, “The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) increased 0.3 percent on a seasonally adjusted basis in September, after rising 0.4 percent in August… Over the last 12 months, the all items index increased 3.0 percent before seasonal adjustment… The index for gasoline rose 4.1 percent in September and was the largest factor in the all items monthly increase, as the index for energy rose 1.5 percent over the month. The food index increased 0.2 percent over the month as the food at home index rose 0.3 percent and the food away from home index increased 0.1 percent.” See chart below.

As a general (if imprecise) rule, when and where supply is roughly the same, higher prices imply increasing demand (or at least persistent demand, despite price increases). During September US fuel and food supplies did not experience significant declines. Producers, distributors, and retailers have experienced increased costs (here and here and here) that are gradually being folded into higher retail prices. Bloomberg explained, “Goods prices, excluding food and energy commodities, rose at a slower pace in September, dragged down by cheaper prices for used cars. Categories that are more exposed to tariffs, including household furnishings and recreational goods, advanced. Apparel prices climbed at the fastest rate in a year.”

So far, many consumers have continued to consume. A recent analysis by the Bank of America Institute found, “Total credit and debit card spending per household increased 2.0% year-over-year (YoY) in September, compared to 1.7% YoY in August… Middle- and higher-income households have stronger wage growth but higher-income spending is likely also benefiting from wealth effects. The discretionary spending of the top 5% of households by income tends to widen compared to the middle-income cohort when the S&P 500 is rising.”

Persistent effectual demand motivates persistent effective supply.