Since 2007 supply chains serving the 2.2 million-plus residents of the Gaza Strip have been constrained by complications imposed by neighboring states. Increasing poverty related to these complications has further suppressed demand and supply. Since early October military operations in Gaza have destroyed critical infrastructure including many supply chain nodes and links. Resupply has been shut down for extended periods (more and more). Evacuations have been tightly controlled (more and more).

Prior to the last eight weeks of destruction and constant disruption, Gaza demand and supply networks experienced much more friction than is found in the high volume, high velocity scale-free flows typically the focus of Supply Chain Resilience. Redundant clustering within Gaza’s hyper-local network featured much higher inventories-per-capita than is typical of US, EU, or supply chains in most advanced economies. These stocks are now mostly drained (after lasting longer than I expected).

According to a 2022 United Nations report, roughly 80 percent of Gaza residents depended on humanitarian food assistance before the recent hostilities. Despite extensive international relief operations, over sixty percent of Gaza residents were already food insecure before the blockade was further tightened and bombing began. Given these conditions, supply chains serving Gaza have long been much more push-oriented than pull-oriented. The World Food Program estimates that only about one-third of food sector capacity has been market-oriented. Potentially surviving market-oriented pull has recently been disrupted by a dwindling supply of currency. After eight weeks of hostilities, the expression of effectual demand is increasingly limited to crowds of hungry, frightened people assembling where they perceive food might be available (here and here and here).

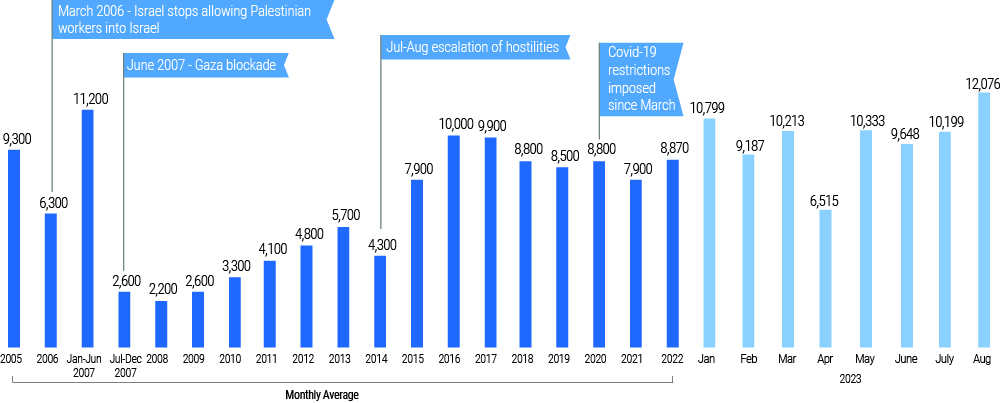

These places do not have enough food available to supply current demand. In recent years approximately 8000 to 10,000 trucks per month have supplied Gaza’s demand for a wide range of goods (see chart below). In October and November, according to the World Food Program, “3,099 trucks, of which 1,249 carrying food assistance have reached Gaza.” Extensive efforts are underway to ensure “continuous and sustained flow of humanitarian aid into Gaza” (here and here and here), but current food flows are barely half that minimally needed for a large population with fewer and fewer options (here and here and here).

Life-sustaining needs exceed current supply. Sufficient supplies are available, but the necessary push is constrained by purposeful policy, severe structural complications, and constant confusion caused by the toxic fog of war. With prior food stocks now mostly exhausted the current catastrophe is fast turning toward mass starvation.

December 10 Update: A reader asks, “Eight weeks in what has changed on the ground or in your mind to prompt “the current catastrophe is fast turning toward mass starvation”? My response: the inventory calculus has changed. Demand volume has remained roughly constant. Demand direction — pull — has shifted considerably because of population displacements. Velocity of supply has been reduced by at least three-quarters volume and direction/discharge has become even more detached from pull signals. This has resulted in a sustained drain of “buffer stocks” held by individuals and institutions. The second derivative — acceleration of resupply — is not (yet?) showing any sustained improvement. I am aware of several efforts to increase acceleration, but I am not yet seeing consistent throughputs. Especially given detached pull signals, supply velocity may actually be deaccelerating. The third derivative — rate of change in (de)acceleration — is outside the scope of evidence available to me. But given reports of intense military operations across the demand-supply matrix, I am pessimistic. Given this calculus, the arithmetic on my conceptual inventory spreadsheet is rapidly approaching zero or negative. I am confident zero is already the reality for many people inside Gaza. As food inventory numbers tack toward zero for more than 2.2 million people the approaching phase transition is unpredictable but predisposed to extremes. In similar cases, we usually see incremental movement of demand (hungry people) to mitigate mass starvation (and reduce demand velocity). Significant efforts (and ability) to restrict such movement increases the likelihood of mass starvation. This week? Next week? I don’t have sufficient evidence to support that sort of precision.

Additional December 10 Update: NBC News provides an overview of the current situation on the ground in Gaza (includes related video). It mostly reflects what was outlined here on December 9. There is also a link to a Friday statement by a WFP official who had just completed a site visit to Gaza. Here is an excerpt, “With law and order breaking down, any meaningful humanitarian operation is impossible. With just a fraction of the needed food supplies coming in, a fatal absence of fuel, interruptions to communications systems and no security for our staff or for the people we serve at food distributions, we cannot do our job… A WFP survey taken during the pause in hostilities, showed that Gazans are simply not eating. Nine out of ten families in some areas spent a full day and night without any food at all. When asked how often this happened, they told us that for up to 10 days in the past month, they had not eaten food.”

December 11 Update: At midnight on Monday morning (US Eastern Time), the Financial Times posted a new report headlined: ‘Catastrophic’ conditions in Rafah as Palestinians reach the end of the line. More evidence, a bit more detail, no new substantive angle, no promising developments… quite the opposite.

A reader notes that, as outlined in my original post’s links, the WFP LogCluster “is following the Red Cross lead.” The reader requested I make available the following links related to the Palestine Red Crescent Society.

PRCS Overview of its response from October 7 to December 4

The ReliefWeb “feed” for PRCS activity

Another reader who is directly involved in logistical support to humanitarian relief organizations in the region writes, “We’re assuming that there’s 0 functioning infrastructure available to frontline groups in Gaza. Anything that’s not already destroyed risks becoming a target, so we’re planning for field conditions. Advocacy to push for the evacuation of critically at-risk / injured people will be important, but if the war continues for much longer, “critically at-risk” will soon include the entire population of Gaza.”

Early December 12 Update: A second channel for security checks of relief supplies has been announced. Additional security check-points are scheduled to open today at the Kerem Shalom crossing and near-by Nitzana, increasing potential velocity and volumes. But, according to I24 news, any cargo approved at Nitzana or Kerem Shalom will then be routed through the same Rafah Crossing currently being used for discharge into Gaza (Kerem Shalom is less than two miles from the Rafah Crossing). To the extent delays for security checks at Rafah (and preexisting checks at Nitzana) have been a significant constraint on throughput, these additional security check-points could help. It is, however, my impression that goods movement beyond the Rafah Crossing has been the most serious constraint in recent weeks. Destruction of the Gaza transportation network, ongoing military operations, and lack of information/coordination are slowing or stopping trucks on the Gaza side of the Rafah Crossing and seriously complicating deliveries further into Gaza . Unless the discharge point allows for continued movement, more volume at a single threshold will increase congestion and exacerbate delays (more and more ). According to a Reuters December 12 report, “… limited aid distributions were taking place in the Rafah district, but “in the rest of the Gaza Strip, aid distribution has largely stopped over the past few days, due to the intensity of hostilities and restrictions of movement along the main roads”. Aid flows were also restricted by a shortage of trucks in Gaza, a continuing lack of fuel, communications blackouts, and growing numbers of staff unable to travel to the Rafah crossing with Egypt because of the intensity of hostilities…” (More)

Late December 12 Update: An official with the Palestine Red Crescent Society has told Reuters the new inspection process at Kerem Shalom did get underway today with 80 trucks from Egypt.

Early December 13 Update: The United States government has increased public pressure for the Kerem Shalom check-point to be reopened for truck movement directly into Gaza. Yesterday Jake Sullivan, the President’s National Security Advisor, said, “We need the capacity that Kerem Shalom provides — on an emergency basis — to get more food, water, medicine and essentials in to be distributed to Palestinian civilians, and we’re putting that quite urgently to the Israeli government to say we are asking you to do this ASAP because of the nature of the humanitarian situation on the ground.” This is a shift from two weeks ago. Sullivan and US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin will depart for face-to-face talks in Israel yet this week. (More and more and more) [CORRECTION: Austin did not accompany Sullivan. Austin will be in the region during the third week in December.]

December 15 Morning Update: According to I24 News, “Israel will now permit trucks to briefly unload goods at the Kerem Shalom crossing on the Gaza side.” This is the first written confirmation that I have seen. I am otherwise hearing that Kerem Shalom is understood by “all parties” as essential to reestablishing minimum-necessary “flows to support Gaza residents.” There is some (loose?) talk of drop-and-go staging inside the Gaza border proximate to the Kerem Shalom crossing. I am not hearing, much less seeing, credible explanations of how what is dropped can be effectively distributed across the demand matrix (see prior note on congestion and here). But getting more trucks — more inbound volume — inside is a necessary and helpful first step. [Reuters and others (here and here) are confirming.]

December 16 Update: The Times of Israel provides an update and review of the “reopening” of the Kerem Shalom crossing.

Before October 7 Kerem Shalom was designed and operated as the principal freight point of entry for Gaza. The site includes roads, security, parking, and staging infrastructure to facilitate well over 7000 trucks per month (mostly food and construction materials). The current reopening anticipates up to 6000 trucks per month being allowed. Restarting flow by unleashing this preexisting capacity is essential. These volumes are fundamental to preventing mass starvation in Gaza. But as every supply chain geek reading this realizes, increased volume requires calibrated velocity or flow will quickly slow and eventually stop as congestion builds. Increasing “outbound” speed and effectively aiming the direction of flow to those surviving in Gaza is now the priority. Kerem Shalom can be translated as “peaceful orchard” or “peaceful vineyard”. If Kerem Shalom is the root, we need its branches and vines to rapidly grow and spread.

December 17 Update: According to several media outlets (most quoting unnamed Egyptian Red Crescent officials) earlier today seventy-nine truckloads of emergency supplies crossed through the Kerem Shalom Crossing into Gaza. According to Reuters, “The aid may not quickly reach those in need. Colonel Elad Goren, head of the civil department at COGAT, told Reuters humanitarian agencies had not increased their capacity to distribute aid to meet the demand from the influx of Gazans who have fled to the south of the enclave on Israeli advice.” (More and more and more.)

December 21 Update: When direct flows from Kerem Shalom into Gaza proper were permitted again on December 16, the turmoil inside Gaza was amplified by a communications blackout (more). This further complicated movement and delivery of supplies within Gaza. As noted in the chart immediately below, the volume of supplies discharged seriously slowed. Many communications networks resumed operations on December 17-18 and volumes recovered — for the first time since October 7 supplemented by entries at Kerem Shalom. On December 18 sixty-four truckloads entered at Kerem Shalom, another sixty on December 19, and another seventy-five yesterday (including a 40 truck convoy from Jordan). I have not, however, been able to confirm if and how the supplies at Kerem Shalom are being further distributed. Recent reports from the Palestine Red Crescent Society have not updated truckload reports since December 16. There have been several media reports regarding disrupted distribution at the Rafah Crossing (here and here). I am receiving contradictory reports on the status of truckloads after entry at Kerem Shalom. As noted — foot-stomped — above, volume is just about useless without velocity meaningfully targeted toward demand. Reuters reports, “Hunger has become the most pressing of the myriad problems facing hundreds of thousands of displaced Gaza Palestinians, with aid trucks able to bring in only a small fraction of what is needed, and distribution uneven due to the chaos of war. Some trucks have been stopped and looted by people desperate for food, while swathes of the devastated territory are beyond their reach because access roads are active battlegrounds.”

December 22 Update: Only eighty-eight supply trucks entered Gaza on December 21. Yesterday a new analysis of food insecurity in Gaza reported, “Around 85% of the population (1.9M people) is displaced, with many people having relocated multiple times, and currently concentrated into an increasingly smaller geographic area. There is a risk of Famine and it is increasing each day that the current situation of intense hostilities and restricted humanitarian access persists or worsens.” (More and more and more and more.)]

December 24 Update: Only forty-nine supply trucks entered Gaza on Friday, December 22. According to COGAT, “In line with the agreement made with the UN, the Kerem Shalom and Nitzana crossings are closed on Saturdays. This measure is to facilitate the UN’s distribution of accumulated goods on the Gazan side of Kerem Shalom and the reception of goods on the Egyptian side of Rafah” On Sunday, December 24 COGAT reported, “113 trucks were inspected and transferred to the Gaza Strip via the Rafah crossing. In coordination with the UN, no trucks were inspected at the Kerem Shalom crossing, due to logistic constraints on the Gazan side of the crossing.” (More and more.)

December 26 Update: According to COGAT, yesterday, December 25, the number of truckloads discharged in to Gaza finally exceeded two-hundred. The 218 truckloads received on Christmas Day is the first time since December 17 this minimum-necessary benchmark has been achieved. But only 83 truckloads were discharged today. Regardless of volumes discharged into Gaza, I am receiving no evidence of improved distribution inside Gaza. Push is entirely insufficient. Push is also almost entirely detached from pull. The PRCS has resumed posting updates.

January 2 Update: I have a new post on the current situation at https://supplychainresilience.org/bad-start-for-new-year/

I will discontinue updates to this post. Future updates will be updated to this new post or future new posts.

+++

Supply Chain Resilience acknowledges that contemporary high volume, high velocity flows of essential human resources serving large populations cannot be replaced, even by the most robust and best-organized relief operations. The only effective and timely way to serve large numbers of survivors is rapid restoration and adaptation of preexisting flows. The current situation in Gaza may be the exception that proves the rule. For sixteen years a huge, dense population has depended on robust, well-organized “relief” operations. Sixteen years of relief operations should have signaled an unsustainable situation requiring fundamental reform. But in the very present crisis, this humanitarian supply chain is the only “preexisting capacity” that has the irreplaceable ability to serve survivors.