As China imposes it’s largest lock-down since the early days in Wuhan, the United Kingdom is shedding the last of its pandemic restrictions. Numbers alone do not explain the distinction. [Updated through April 4, see below.]

According to the South China Morning Post, “Shanghai reported 3,500 new locally transmitted cases on Monday, most of them with mild or no symptoms. More than 10,000 infections have been found through mass testing in the past week – over 9,900 of them asymptomatic.” (More)

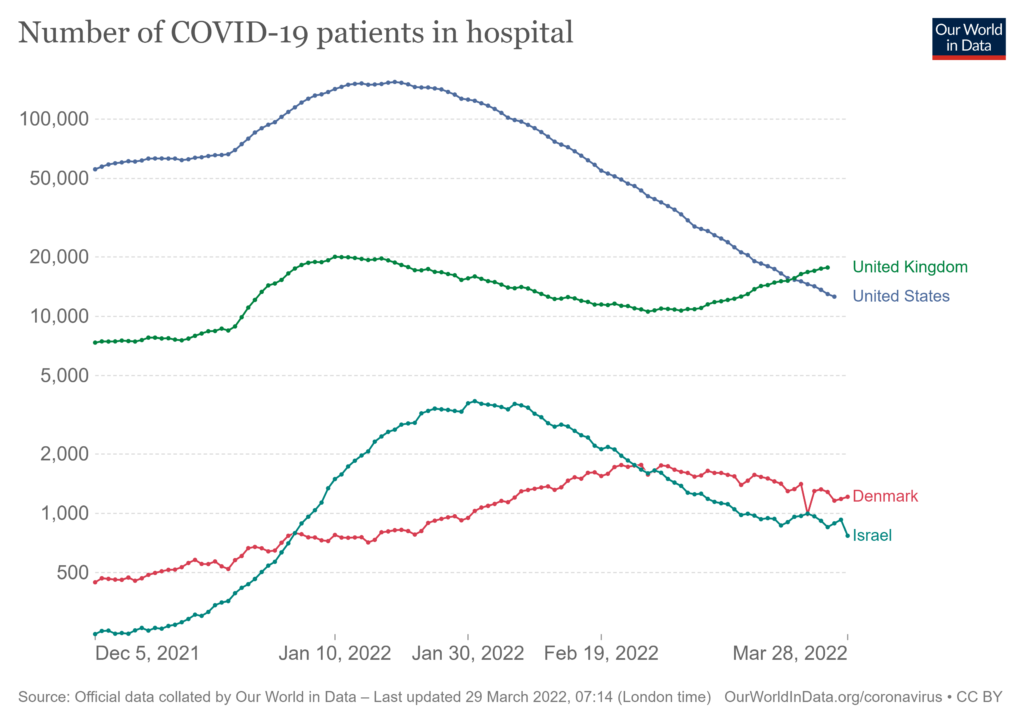

Over the weekend the United Kingdom confirmed more than 215,000 new infections. The recent surge in the BA.2 variant has hit Scotland especially hard. But Scotland’s legal restrictions related to covid were still discontinued on March 21. Wales has since taken similar steps. England began unwinding last month, even as hospital beds were filled about as much as during the omicron surge (see chart below)

China’s legal, political, and cultural context facilitates more rigorous restrictions than the UK. China’s public health demographics arguably justifies more containment. Vaccination rates in Shanghai are close to 80 percent, but Sinovac (CoronaVac) has demonstrated less efficacy against omicron and BA.2 (more). More than 130 million Chinese over age 60 have not been vaccinated. British vaccination rates (with a so-far more efficacious mix of vaccines) have approached 90 percent of the over-sixty population. The United Kingdom has hospital intensive care capacity about one-third larger than China. Different risks motivate different responses.

It is also worth acknowledging that the risk of more virulent mutations persists in China, UK, and wherever transmission invites adaptation.

The Wall Street Journal observes, “A lockdown in Shanghai marks another potential setback for China’s export machine, reigniting concerns over the risk of renewed disruption to global supply chains pummeled by the pandemic and war in Ukraine.” This is possible. There is also evidence that disruptions can be mitigated.

Supply chains prefer — work hard to create — continuous, predictable flows. What we are seeing in China — the world’s largest exporter — is analogous to a three-year-old fascinated with toilet flushing downstairs while upstairs a teenager is in the shower. Big sister may still get clean enough, but she will not be happy. Mix in disrupted financial and commodity flows (especially for petrochemical and agricultural volumes) related to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, some indiscriminate cyber destruction, and a host of other risks and the whole family feels very much on-edge.

March 31 Update: According to the Financial Times: “China’s manufacturing and services activity contracted in March for the first time in almost two years, highlighting the economic strains of the government’s strict coronavirus measures. The official manufacturing PMI, a gauge of factory activity in which a reading of 50 separates monthly expansion from contraction, fell to a five-month low of 49.5. The non-manufacturing PMI dropped to 48.4, its lowest level since August.”

According to Loadstar: “The Shanghai lockdown is playing havoc with Chinese supply chains, driving up inland logistics costs and disrupting shipping schedules…”

April 1 Update: Bloomberg has a long-form assessment of China’s options — and potential implications for the rest of us.

April 3 Update: All of Shanghai is now locked down. According to the Financial Times: “Shortages of food and medicine have left residents in China’s biggest city desperate and frustrated as authorities struggle to gain control of a Covid-19 outbreak.” According to an April 2 report in the Global Times (Chinese language, official Communist Party publication), a new variant of coronavirus is now confirmed as being transmitted in Suzhou, near Shanghai, “The infection was sequenced and compared to the BA.1.1 evolutionary branch of the VOC/Omicron variant strain. No highly homologous sequences of the novel coronavirus genome were found in the database.” (Google translation). Meanwhile in the United Kingdom, last week the coronavirus infection rate reached an all time high (more), without prompting new public health measures. The currently surging BA.2 version of the virus is highly contagious but typically features mild morbidity. Does the high transmission rate increase mutation probabilities? Yes. Britain is betting its “carry on” approach to living with covid is worth the mutation risk (more and more). China has, so far, decided the risks remain too high. But containment costs have also accumulated and are increasing. By Easter BA.2 will almost certainly be surging in many parts of the the United States.

April 4 Update: The Financial Times has a long-form assessment of China’s counter-pandemic policy and practice: “the measures introduced in Shanghai on March 28 highlighted the government’s commitment to a now-globally unique strategy — fine-tuned across outbreaks from Xi’an to Shenzhen — of attempting to completely eliminate local cases no matter the economic and social costs.” Bloomberg is reporting on new mutations (more). This report’s tone and details are cautiously optimistic, emphasizing cautions. Loadstar reports, “Covid lockdowns in China, war in Ukraine and the threat of hyper-inflation are a toxic mix of unpredictability for liner trades, but they have so far not had an impact on container freight rates. Indeed, container spot rates, although trending down, are broadly in line with normal seasonal falls and, moreover, ocean carriers are succeeding in driving-through significant contract rate increases.”