My supply chain — or better: demand and supply network — angle on the pandemic emphasizes the need to effectively manage demand for hospitalization. From a network perspective, supply of hospital care is the bottleneck that most often requires mindful exploiting (ala Goldratt). When hospitals are overwhelmed the network experiences more disease and death. When demand for hospital care remains within supply capacity, disease and death can be systematically mitigated across populations.

Hospital congestion is bad. Hospital flow is good. Local to regional demand is the flow factor most readily influenced. As is often the case, supply capacity is finite. Available medical staff is often the acute rate-limiting factor for hospital care.

Most people infected with covid-19 have not needed hospitalization or even much medical care. But a significant fraction of those infected have experienced severe illness (here and here and please see this caveat). The elderly, those with preexisting respiratory conditions, and the immuno-compromised are especially likely to require hospitalization. There have also been mysteriously deadly cases involving the young and seemingly healthy.

Vaccination, avoiding crowded interior spaces, social distancing, reduced circulation, and facial coverings are demand management techniques for slowing and containing transmission vectors across populations. The “consumer” often perceives these as self-protecting behaviors. But from a flow perspective, these are other-protecting measures, even network-protecting measures. Being vaccinated makes it much less likely that a person will transmit the virus to others. Encounters between vaccinated persons are much less likely to give the virus a mutation opportunity. Less transmission and less mutation equals less demand for hospitalization.

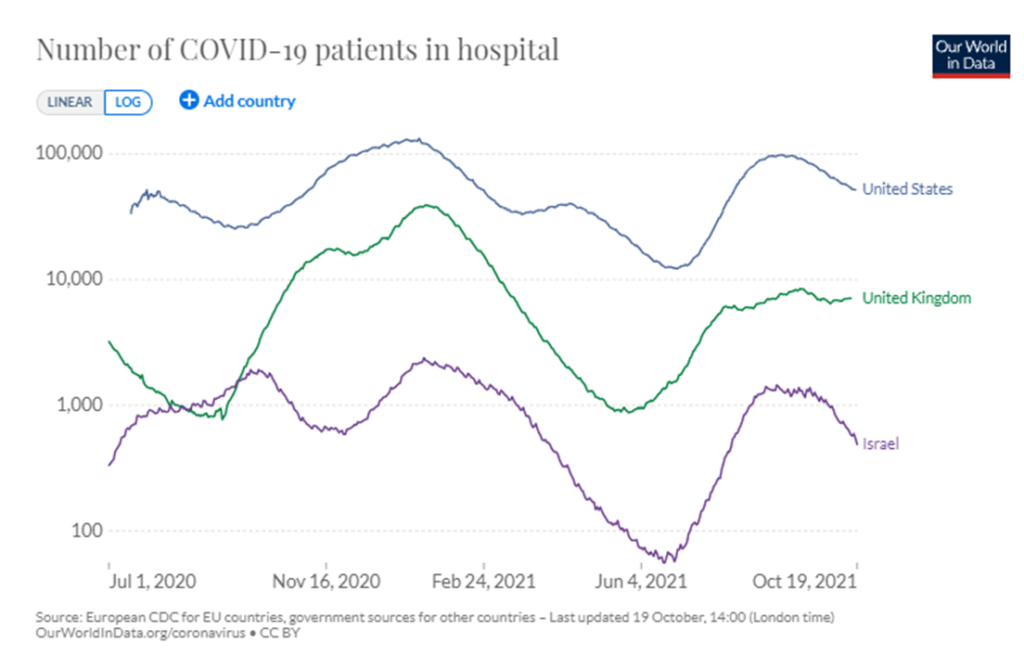

I have been tracking hospitalization rates in Israel, United Kingdom, and the United States. Obviously, these are three very different contexts. But each nation was early to make vaccines available and vaccination was well-along before or early-in the spread of the Delta Variant. Data quality on hospitalization can be a problem, but Israel’s small and sophisticated healthcare network may have the best data-integrity in the world. The British National Health Service is also data-savvy. The fractured US healthcare system creates plenty of data challenges, but overtime more accurate, real-time outcomes are being reported.

On October 19 Israel had at least 540 people hospitalized with covid, the UK (mostly England) had about 7000, and the United States had almost 52,000 people hospitalized with confirmed cases of covid. While the raw numbers are hard to compare, I find the logarithmic display (as below) — showing the rate of change — to offer something close to comparable demand curves for hospitalization. All three are doing better than late July or early August. But the numbers remain much higher than had been hoped when vaccination campaigns began. The UK’s persisting plateau is of particular concern.

According to The Financial Times (October 15):

The UK’s weekly death rate stands at 12 per million, three times the level of other major European nations, while hospitalisations have risen to eight Covid-related admissions a week per 100,000 people, six times the rate on the continent. The decision to end compulsory mask-wearing and to pause plans for vaccine passports in England has made the British government an outlier for its management of the pandemic and could account for the worsening trends, according to scientific experts. (More)

According to Reuters, “Four months into one of its worst COVID-19 outbreaks, Israel is seeing a sharp drop in new infections and severe illness, aided by its use of vaccine boosters, vaccine passports and mask mandates, scientists and health officials said.

On October 18 the FT also reported:

Scientists are anxiously tracking a descendant of the Delta coronavirus, which is responsible for a growing proportion of Covid-19 cases in the UK, and could be more infectious than the original Delta variant, they say. This AY.4.2 subvariant has only recently been recognised by virologists who follow the genetic evolution of Delta but it already accounts for almost 10 per cent of UK cases. Its prevalence is increasing rapidly, though not as fast as the original Delta variant when it reached Britain from India early this year. (More and more and more.)

Israel has just confirmed its first case of AY.4.2. So far six have been confirmed in the United States. Waaay too soon to raise any alarms.

Quite the contrary, I will confess that my attitude toward covid has shifted in the last two or three weeks. I want to acknowledge that a combination of vaccination and natural immunity — assisted by modest behavioral adjustments — could reduce US viral risks to something akin to automobile injury and death (even less for vaccinated persons). Covid and car wrecks could even compete over bad luck and bad behavior as co-conspirators. (More)

But while my attitude is shifting, my considered judgment is not yet persuaded. It is waaay too soon to decide the next mutation (or two) will not be worse than Delta. As the contrasting accounts of Israel and the UK suggest, it is also waaay too soon to put aside behavioral cautions. Credible data does not (yet) signal anything more than continued uncertainty. So… if you can, get vaccinated if you are not; if you have been vaccinated, prepare to get your booster; avoid interior crowds; give other folks plenty of space; minimize travel; and cover your nose and mouth when you cannot avoid sharing interior spaces. When for practical or social reasons you cannot take all of these network-protecting, other-protecting steps, please do what you can whenever you can.