Workforce constraints caused by omicron may be peaking. There is certainly plenty of evidence for ongoing friction, but also a few signs of constraints beginning to loosen.

New covid cases continue to clock-in at a very high rate (see first chart below). The United States hopes it is following the UK’s demand curve, not Denmark’s nor Israel’s (more and more).

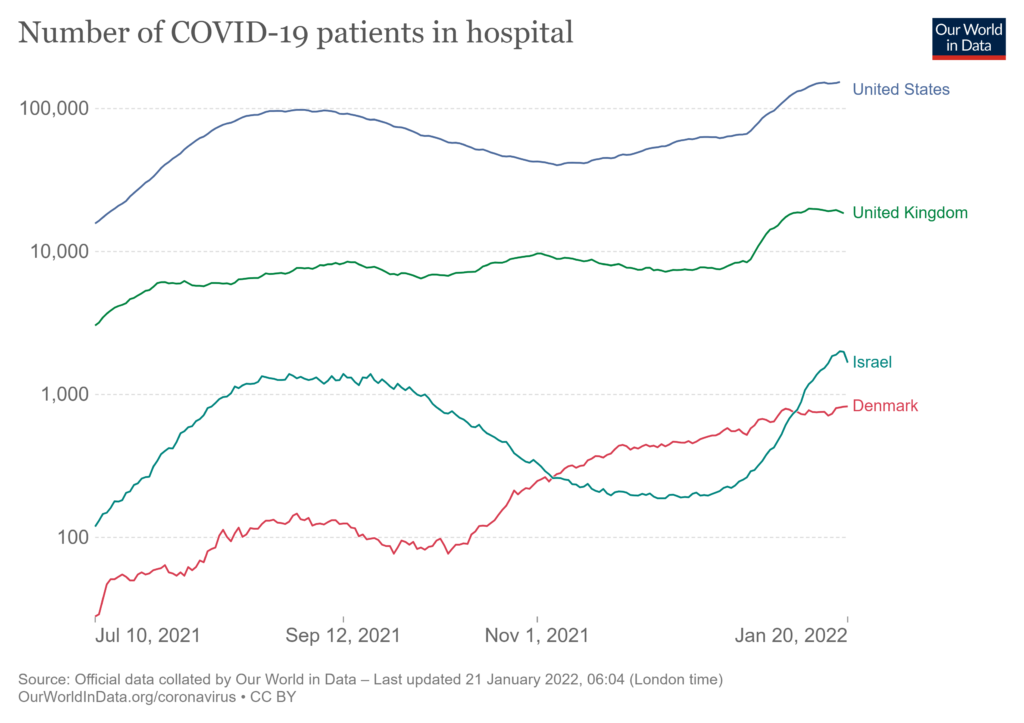

Proportionally, the omicron variant continues to cause fewer hospitalizations than some prior strains (see second chart below). But the number of US residents in hospital with covid has never been higher. Given several benchmarks, higher US covid hospitalizations are likely still ahead. Hospitalizations are a reasonable indicator for disease penetration of supply chains.

According to an experimental U.S. Census Bureau survey (data tables) at some point between December 29 to January 10 more than 14 million employed Americans were not working because they were infected with covid or caring for someone infected or caring for a child whose daycare or school had closed (more and more). If accurate, this is serious friction. (See another Census survey of small business for interesting angles on sectoral and geographic differentiation.)

Since omicron began its surge, more US workers have also been laid-off and applied for unemployment insurance as demand fell for several retail service categories. Last week new and continuing jobless claims saw significant increases, apparently surprising many… despite dramatically increasing case counts and reduced retail activity since Thanksgiving (more).

I have asked colleagues around the country about outcomes of omicron related workforce absenteeism. In the last couple of days three front-line folks told me:

“We are seeing flash-droughts of specific upstream SKUs. If downstream customers notice reduced flows of a category leader, the whole category will be wiped out between deliveries. Midstream can’t overcome that kind of push-pull.”

“Denver is crazy because of the Kroger strike. The Mid-Atlantic and Upper Midwest are crazy because of winter weather. California is crazy because it’s California. Volumes are high almost everywhere. Reefer madness everywhere. There’s no fat anywhere in the system. Add absenteeism and crazy can quickly crash.”

“The big picture is ambiguous because local conditions are highly variable. AND that local variability (call it “diversity”) is what ‘s really keeping the whole system going.”

Given omicron’s swift success at workforce subtraction, preexisting and persisting shortfalls in the number of new truckers working, and unprecedented levels of demand (our inventory of woes could continue), the resilience of US flows can inspire awe (at least from me).

Grocery is a fast-adapting example. Stresses across the sector are real: upstream, midstream, and downstream (more and more). Individual stores and neighborhoods and therefore households are experiencing disrupted flows and increased prices. But according to credible estimates, system-wide flows are mostly fulfilling stubbornly strong demand. According to the IRI CPG Supply Index at the end of last week (January 16), overall retail grocery shelves were 89 percent fully stocked (compared to pre-pandemic benchmarks). The biggest shortfalls were in the tobacco and alcoholic beverage categories (80 and 84 percent respectively). Given this week’s turmoil, I would not be surprised if stock-outs increase by another one or even two percentage points. But there is plenty of flow to feed us, even to supply our next stiff drink.

Recent grocery flows in Australia, Canada, and China demonstrate that equally sophisticated supply chains have not been equally resilient (more).

It is waaay too soon for a conclusive assessment, much less a victory lap. But here’s my working hypothesis: scale matters, diversity matters, and adaptability — especially self-organization — matters. Where and when there is more of each variable — scale, diversity, and adaptability — there will be more resilience.

It is also essential to acknowledge that the covid crisis is disrupting our networks rather than destroying our networks. We need to be mindful transferring what covid is teaching us to the destructive context of major earthquakes, climate change, high-category hurricanes, and other network-shredding forces.