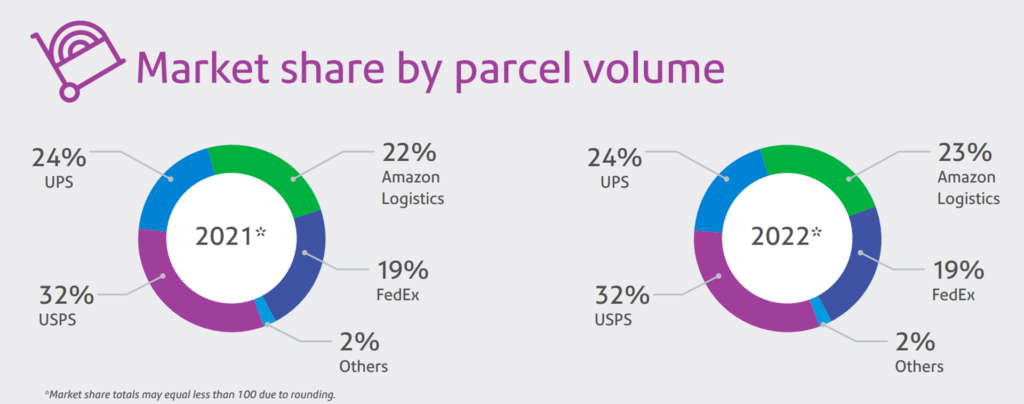

In 2022 UPS averaged more than 20 million deliveries per day (source). This reflects roughly a quarter of national parcel delivery flows (see chart below). Over 80 percent of UPS volume is NOT next day or expedited. Last year Business-to-Consumer (B2C) shipments represented roughly 60 percent of average daily volume (B2B is most of the remainder).

UPS is especially focused on maintaining and growing volumes/profits associated with serving Small and Medium-sized Businesses (SMBs, accounting for about 30 percent of total UPS volume, more). Only three-hundred eighty UPS customers are the source of about one third of total volumes. These bigger volume shippers are in an especially uncomfortable place in case of a strike. They have also been the most proactive in arranging alternatives. But Monday one long-time shipping friend confessed, “I’ve been working contingencies since early June but can’t find any real alternatives. Many B2C will not be shipped and many that are shipped will probably go missing until long after any strike is over.”

Amazon is a big UPS customer, accounting for 11.3 percent of 2022 UPS revenue (it was even higher in the past). In recent years this key relationship has become more competitive, as each party became increasingly concerned by their dependence on the other. Amazon now has substantial self-shipping capacity (see chart below). Mutual “de-risking” is underway and more is planned. Combine this dynamic with huge shifts and swings in parcel delivery prompted by the pandemic and even more caution than usual is needed when trying to use past-history to predict future outcomes. The 1997 UPS strike might as well have happened on another planet in terms of potential economic consequences (more and more).

The healthcare category is another UPS strategic priority. According to the CEO, “Our goal is to become the number one complex healthcare logistics provider in the world.” According to the CFO, during the first quarter of 2023, “Logistics delivered revenue growth driven by gains in our healthcare logistics and clinical trials business and increased operating profit.” UPS began focusing on medical and life science logistics prior to the pandemic. The UPS contribution to rolling out cold-chain solutions for covid vaccines accelerated the scale and calendar for this strategy. The 2022 UPS purchase of Bomi, an Italian healthcare logistics firm (here and here), reflects the significant priority UPS gives this higher margin product category. The UPS Healthcare unit earned about $9 billion last year and has been expected to earn $10 billion plus this year (sans a Teamsters strike).

In the event there is a Teamsters strike against UPS, parcel deliveries will be disrupted and delayed (more). The other big players in parcel delivery, including Fedex and USPS, do not have current capacity to absorb total UPS flows. Credible, data-informed analysis suggests less than one-third of UPS flows could be effectively carried into other preexisting parcel delivery flows. Moreover, if these others are undisciplined in trying to fill the gap, their effort to serve real needs (and claim market-share) will create knotty congestion in their own networks. While the strike continues, everyday in August will be Christmas in terms of volume potential for other players.

There is existing excess capacity in the Less-Than-Truckload (LTL) service sector. LTL can help fill the gap in local, regional, and long-distance logistics, but NOT for last-mile direct-to-consumers. There are other parcel carriers and courier-type service providers (e.g. Uber, DHL, more) who will offer services to fill the last-mile gap. Prices will be higher and delivery times will lengthen, especially in more rural and other less intensely served geographic areas. Last mile will remain a challenge despite creative adaptations (though less challenging than would have been the case pre-pandemic, now that there are many more direct-to-consumer options).

Specific to medical and other life science products, there is existing excess capacity in the refrigerated transportation service sector (reefers). This sector will — already is — stepping up to provide UPS customers (and their customers’ customers) with options. But given constrained capacity, allocation decisions are likely… and allocations almost always generate collateral damage to overall network velocity and therefore volumes.

Any loss of preexisting flow this significant is a bit like going to war: suddenly a battalion of previously unrecognized interdependencies can — almost certainly will — come over the hill screaming and shooting.

But given what is set out above, I am most concerned about potential slow-downs and last-mile impediments related to medical goods, pharmaceuticals, and related life science product categories. This would be the first strike for the relatively new UPS Healthcare unit (and very new unit leader). These are especially time-and-quality sensitive products. Alternate sources of delivery are not abundant, especially in terms of last mile capabilities.

Home delivery (AKA “prescription delivery”) of chronic care medications is increasingly common. USPS and UPS are the most common delivery options for this product category. UPS can handle some controlled-substances that USPS will not handle (example). A loved one receives her blood pressure medications every 90 days (more or less). She currently has in-home stock sufficient through mid-September. The longer a labor action lasts, the more likely lack of timely and confident delivery options will create nervous buying — and diminished at-home inventory — that will prompt both urgently true and misleadingly false demand signals… hoarding… and other congestion-causing behavior in healthcare networks.

The anticipated labor action is unlikely to have a significant impact on upstream production. Core downstream demand for parcel delivery and other UPS services is unlikely to significantly shift in the near-term (and has recently been softening). But given the high proportion of midstream flows that depend on UPS capacity — and the potential slowing or stopping of these flows — demand signaling is likely to escalate and capacity will not exist to effectively fulfill demand.

Last Saturday when I asked my loved-one about her blood pressure medications, she had not given any recent thought to her prescription delivery schedule or current supply on-hand. Given her current inventory, the possible strike should not impact her. But for those whose prescriptions will run-out in the next three to six weeks, re-filling now could avoid serious problems in the near-to-mid term… and reduce stress on networks that will be plenty stressed if the strike happens.

I have asked — but have not received answers — on the following questions:

1. Can HHS or FDA or others identify which high-volume chronic care medications are NOT handled by US Postal Service? I bet these medications are sourced from a sparse handful of places/players. Does HHS etc. know who and where? In extremis could USPS handle these products? In any case, which high volume chronic care products will be most constrained by a strike? Are there other essential medical goods, pharmaceuticals, or life sciences products for which UPS is an especially high-proportion carrier?

2. Does HHS or ASPR or others know — or can they find out — if all UPS Healthcare flows also depend on Big UPS nodes, links, and labor… or are there some legacy (or otherwise) non-union carve-outs? Does UPS Healthcare have capabilities to procure third-party logistics support during a strike? Does it plan to do so? Is the plan actionable? Will the Teamsters actively resist or focus elsewhere?

There are obviously plenty of other questions… and potential problems… and possible mitigation measures. We now have just over two weeks to do our best to be ready, while the Teamsters and UPS consider their options. Just In Case, while still hoping for Just In Time.