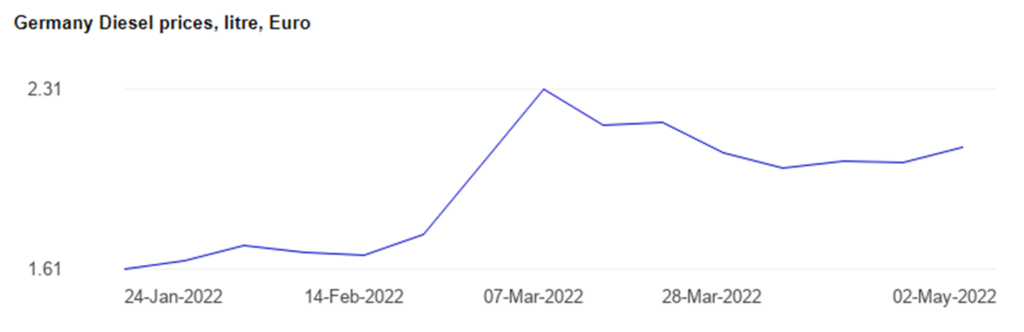

[ May 13 update below.] Russian refineries typically sell a significant portion of their diesel fuel to European customers (more). Early-stage European sanctions related to the Russian invasion of Ukraine complicated, but did not stop this flow (also see second chart below). The complications and partial constraints did, however, increase prices. For example, the chart immediately below shows the average Euro price of a liter of diesel sold in Germany since the end of January. In the last few days the price has increased again as an oil-specific set of EU sanctions may be implmented (more and more).

Facing current complications and future uncertainty, diesel buyers in Europe turned to North American, Middle East, and Asian refineries for increased diesel flows (see chart below). Especially since global prices escalated, refiners have been motivated to sell. In the case of US Gulf Coast refineries the atypical European demand coincided with increased diesel demand from established Latin American markets (more and more). In late April, according to Bloomberg, “Waterborne diesel exports out of the U.S. Gulf Coast have climbed to 1.04 million barrels per day so far this month, on track to hit the highest level since August 2019, according to estimates from oil-analytics firm Vortexa. Volumes to Europe have seen the biggest jump in the period to 84,700 barrels per day, on course for an eight-month high.”

Given solid international diesel demand and higher prices, over the last several weeks many US refiners have sold inventories and increased diesel production (constrained by fixed capacity, probably the most important link in this post). According to the US Energy Information Agency, as of the end of April US diesel inventories were less than half 2021 same-time levels in New England and the Mid-Atlantic and about one-fifth lower along the Gulf Coast and the lower Atlantic. Since the invasion of Ukraine, diesel imports (typically an important part of the mix in New England and the Mid-Atlantic) have fallen from over 400,000 to barely 100,000 barrels-per-day. Meanwhile US diesel exports have increased almost 50 percent since early March.

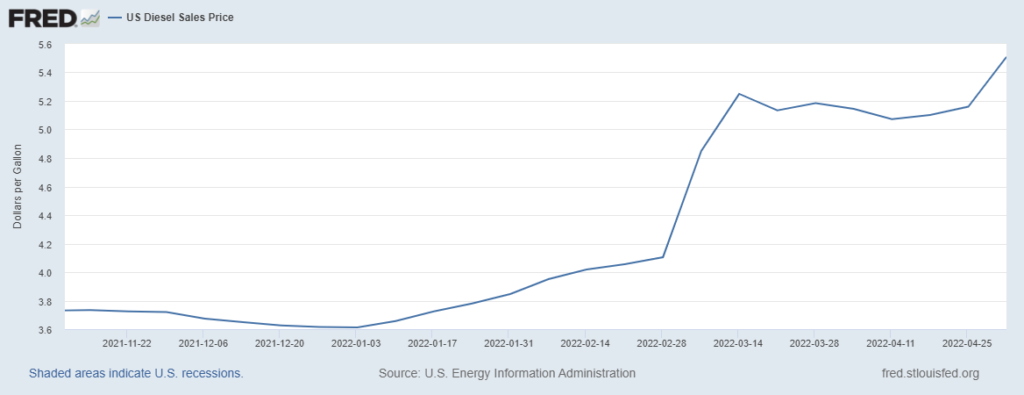

US domestic diesel demand has been mostly within recent seasonal averages and slightly lower than last year. As a result, even though the US average retail price for diesel has also spiked (see chart below), there has been an incentive to serve displaced demand in Western Europe and nervous demand in Brazil. Part of the risk calculus — and related urgency — has included the possibility of an early end to the invasion of Ukraine restoring full-speed Russian diesel flows and lowering prices. [Late on this Victory Day, the “risk” of an early end seems considerably reduced.]

The reduction in diesel inventories has been especially pronounced in US east coast markets served by the Colonial Pipeline. Colonial’s Line 2 moves diesel from Gulf Coast refiners to Greensboro, North Carolina. Line 4 delivers diesel from Greensboro to Linden, New Jersey. It typically takes at least two weeks and up to twenty-four days for refined product to move end to end. In the current market environment, this means diesel in the pipe is more or less creeping inventory. According to several market sources (more and more), since early March Colonial has loaded much less diesel than usual. S&P interviewed an official with the largest US refiner:

Brian Partee, Marathon’s head of clean products, said that increased distillate exports have tightened the US Atlantic Coast market, which is seeing lower European imports as well as lower flows up the Colonial Pipeline, the main conduit of refined products from the USGC refiners to New York Harbor. But this is a function of timing, and the “run-up in the prompt front end of the cycle,” he said, allowing Marathon to capture current high diesel prices immediately through export rather than waiting for the time it takes diesel to move up the Colonial Pipeline.

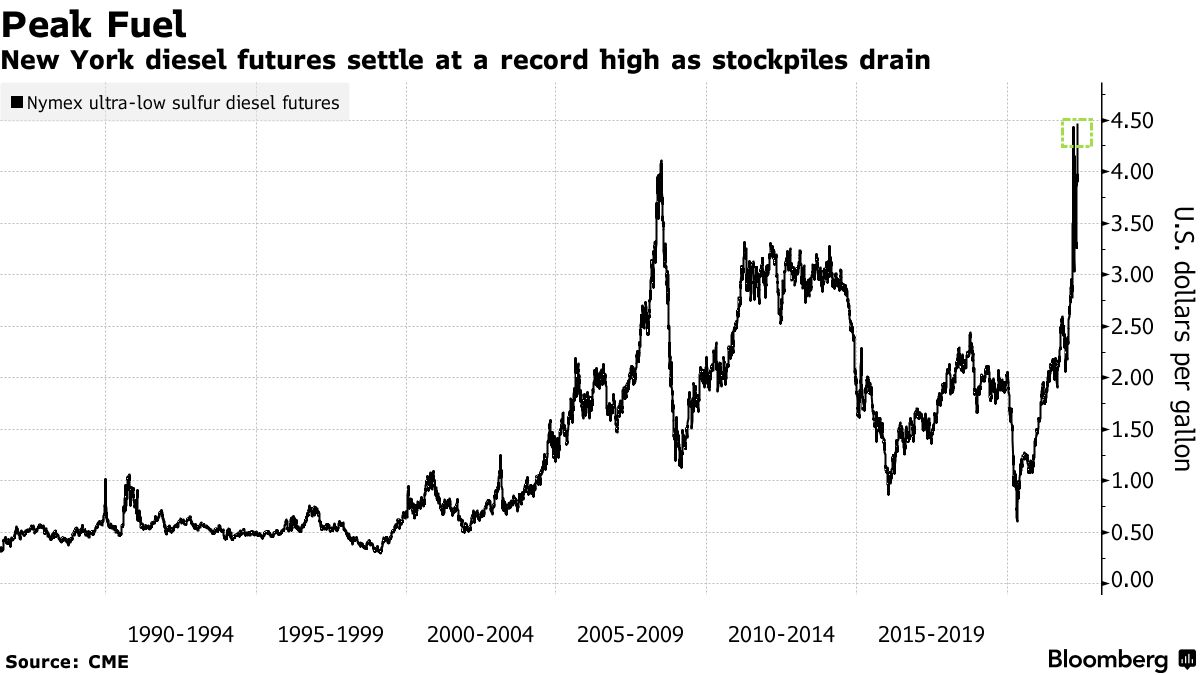

At the end of April there was a significant price surge for diesel contracts in the New York Harbor market (see chart below). According to Bloomberg on April 26:

Diesel futures trading in New York surged to the highest level in records going back to 1986 as global demand for the fuel remains robust in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Nymex ultra-low sulfur diesel futures settled at $4.4679 a gallon on Tuesday, exceeding the prior record on March 8, when the U.S. formally sanctioned Russian oil. Since then, diesel has become the world’s most in-demand fuel as buyers in Latin America, Europe and within the U.S. compete for supplies as fast as refiners on the U.S. Gulf Coast can make them.

This additional pull should attract additional push up the Colonial Pipeline. You can follow the price and futures action here.

May 10 Update: According to the Financial Times and others, European Union and G7 efforts to develop oil-specific sanctions on Russia are faltering. “Brussels has shelved its plans to ban the EU shipping industry from carrying Russian crude as it struggles to push through its latest sanctions package because of anxiety among some member states about the economic impact of the measures.” Other potential oil-specific sanctions — while still being negotiated — have also encountered resistence from EU member states. S&P reports, “Crude oil futures were sharply lower in mid-morning Asian trade May 10, extending steep overnight declines, as recession fears, hurdles to an European Union-ban on Russian oil and the ongoing spread of COVID-19 in China saw sell-offs across the financial markets.”

+++

May 13 Update: The Wall Street Journal reports, “… the price for the diesel fuel that is crucial to industrial business has continued going up. That has added to rising costs in supply chains and to inflation pressure on things from housing construction to deliveries of consumer goods. The costs are hitting smaller trucking fleets that make up the bulk of the highly fragmented U.S. trucking market particularly hard, worsening cash flows for businesses that tend to be lightly capitalized with little cushion to absorb sharp changes in costs.”