[Updates Below] Flows of fossil fuels — especially diesel — are much more viscous than usual. Sources of many manufactured products in China have been cut-off or slowed. Disequilibrium has deepened (again) between demand and supply for semiconductors. Flows of easy credit are being purposefully curbed. The specialty formula debacle has unnerved many who are not involved in feeding infants. Food and related — such as wheat, fertilizer, sunflower and palm oil — are stuck behind enemy lines or maritime blockades or defensive walls of export controls.

In each of these cases the cause is not a loss of core capacity or even — yet — lack of abundant supply. Rather, government actions intended to mitigate plague, war, inflation, or hunger are complicating or curtailing flows from going where they would often otherwise go.

In most cases, the policy intentions are unimpeachable (Putin’s excepted). Execution is innately complicated and too often can be clumsy, contradictory, and even self-subverting (Putin’s Ukraine policy is a fair example). Recent outcomes are prompting concern or alarm or, in some places, panic. For many of these flows, current risks have been amplified by a long series of choices — both public and private — that have concentrated supply or demand or both, pooling risk in fewer places and players. The resulting structure tends to amplify both good and bad. Just now, bad seems ascendant.

Time, space, and cost constraints are fundamental in each of these flows. Some of these flows — ultimately, all of these flows — are interdependent. Taking on one problem can cause two more. As always, there is a risk of the urgent obscuring or fatally delaying opportunities to engage what is most important.

The time-dimension of growing food pushes me to give food flows strategic priority.

For the highest volume global food producers, agriculture is seasonal. Crops must be planted in different places encompassing enough space within a particular time-frame or yields will suffer. Sufficient water and fertilizer must be applied in a timely way or yields will suffer. Harvesting must be completed within narrow seasonal constraints or yields will suffer.

Once the harvest is gathered other time-and-space factors accumulate, but these tend to be much less austere than the planting-to-harvest temporal “bottleneck”. There is cause to perceive that China’s manufacturing capacity will be reengaged whenever policymakers decide to get out of the way. Carbon extraction and fossil fuel production are not seasonal. Meanwhile, wheat or corn or barley is produced this season — or not.

Too much food — especially too much wheat and sunflower oil — is currently trapped in Ukraine (more). There are roughly 22 million tons of last year’s harvest still in storage across Ukraine. With Odesa, Kherson, and other major Black Sea ports blocked, these stocks are seeking other routes. For example, the Romanian port of Constanta is less than 300 miles south of Odesa and familiar to Black Sea carriers (more). These innovative flows have near-term implications for feeding millions in the Middle East, Horn of Africa, and South Asia. As of mid-May Ukraine’s grain exports are only about one-third of last May’s volume.

Moving last-year’s harvest is also necessary to make room for this year’s harvest. In early May it was estimated that even in the midst of war Ukraine’s farmers may be able to plant about 11 1/2 million hectares — about one-fifth to one-quarter less than usual. In recent years Ukraine’s proportion of global grain exports has been a bit more than ten percent overall, but well over half for specific markets such as Egypt, Indonesia, and Pakistan (more). The United Nations World Food Program has also purchased significant amounts of Ukraine’s grain for emergency food assistance. Depending on yields and flows from other grain producers, losing two percent or marginally more of international grain exports ought not be catastrophic.

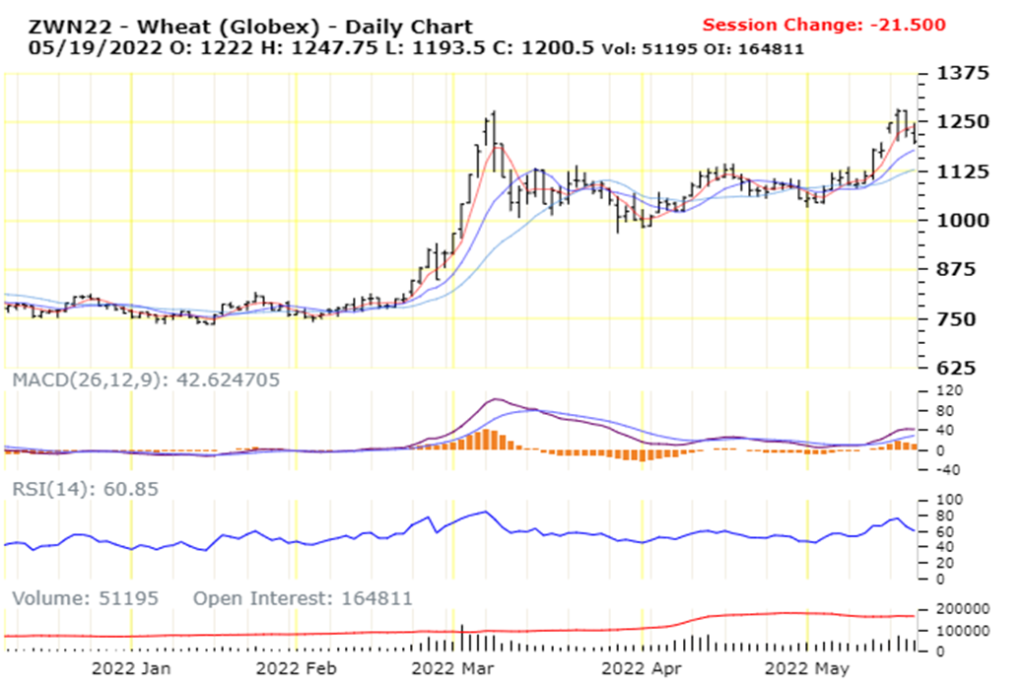

But as of mid-May only about one-third of Ukraine’s lower-than-usual number of hectares had actually been planted. Fuel and fertilizer shortages in Ukraine are complicating planting (more). It is reasonable to assign a risk premium for harvesting whatever is finally planted. As a result, Ukraine’s reduced food output is causing a price surge in several food commodities, especially wheat. There are other risks: Russia is usually a major grain exporter too, but its exports are complicated by sanctions. Due to drought, this year’s US winter wheat yields were well below normal. Heavy rains decimated China’s winter wheat harvest. Below is a chart that provides one angle on wheat futures contracts since the beginning of the year. (More.)

Even with price controls, in Egypt bread costs at least one-quarter more than one year ago. It is getting more difficult to find bread to buy in Lebanon. (More and more and more). Many countries do not have sufficient dollar reserves to buy enough higher priced grain to fulfill local demand.

Some key food supplies are tighter than typical just now. Given what is not happening now, supplies could be even tighter next Spring. In some places that typically depend on food flows from Ukraine and Russia, delays and uncertainty are prompting pull signals (price increases) to fill the gap between demand and supply with flows from other places. While this stronger pull is motivating the emergence of new push channels, some downstream prices now exceed the local ability to pay. Demand persists, but an increasing proportion of demand cannot be effectually expressed and is essentially being excluded from pull and push (see Yemen, Somalia, Sri Lanka, etc.).

As the links above and this week’s UN Security Council special meeting demonstrate, the problem with food flows is well-recognized. It is not, however, claiming the priority required to make practical progress. Disrupted Ukrainian food flow is a problem that will get worse without sustained, significant action starting now. Key steps should include:

- Maximize and optimize the Constanta Corridor for discharge of Ukraine’s food exports.

- Increase deliveries of fuel, fertilizer, and other key inputs to Ukraine’s farmers.

- Reinforce effectual food demand for people in places where pull signals have encountered the most interference due to currency gyrations and physical disruption of preexisting supplies.

Ukraine is an important preexisting node in global food flows. Reassuring markets that these flows are likely to persist will reduce price volatility for everyone. Focusing on preexisting network capacity and players is the most efficacious means for doing this. Providing effective mechanisms for expressing real demand will target flows and reduce misdirection caused by consumer hoarding or market manipulation or dependence on relief programs.

Global networks of demand and supply are morphing in response to Ukraine’s flows and future possibilities. To the extent upstream push can be more confidently anticipated and downstream pull can be better balanced, midstream rapids or portaging can be minimized. And… famine threatening hundreds-of-thousands can be avoided.

+++

May 24 Update: Bloomberg reports: “Russia has continued to ship its wheat at the now-higher price, finding willing buyers and raking in more revenues per ton. It is also expecting a bumper wheat crop in the next season, suggesting it will continue to profit from the situation. Global wheat prices have risen by more than 50% this year, and the Kremlin has collected $1.9 billion in revenues from wheat export taxes so far this season, according to estimates from agricultural consultant SovEcon.” While this is unwelcome in terms of sanctioning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it is good news for flows and fulfilling demand. Bad can sometimes unveil good. The reverse is also possible. The full Bloomberg report is helpful to read.

May 25 Update: Reuters reports: “Russia is ready to provide a humanitarian corridor for vessels carrying food to leave Ukraine, in return for the lifting of some sanctions, the Interfax news agency cited Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Andrei Rudenko as saying…” (more and more and more and more). LATE ON WEDNESDAY: Bloomberg reports: “Russia’s Defense Ministry said it’s opening two sea corridors for international shipping from seven Ukrainian ports, after growing international criticism of an unfolding global food crisis triggered by a Russian blockade.” (More)

May 26 Update: Bloomberg reports: “The Netherlands would consider joining an alliance to send warships to escort grain supplies stuck in Ukrainian ports but would need assurances from Russia and, ideally, involvement from Turkey, according to the Dutch defense minister. Estonia and Lithuania have been calling to establish a coalition of the willing to send naval escorts for grain freighters, as European officials decry Russia’s effective blockade of Ukrainian ports that’s left Kyiv struggling to get grain shipments out.” (More)

Above in my original post I focused on the Constanta Corridor — instead of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports — because I considered the prospect of Russia cooperating to be scant. The Constanta Corridor should still receive priority attention. But the last two days suggest a slightly improved possibility of restarting flows from preexisting nodes using preexisting channels… which would certainly be the most effective and expeditious means of reclaiming prior capacity. There is also an urgent need to address the second priority noted in the original post: supplying Ukrainian farmers who are currently planting the fall harvest. Their fuel supplies are very tight and tightening.

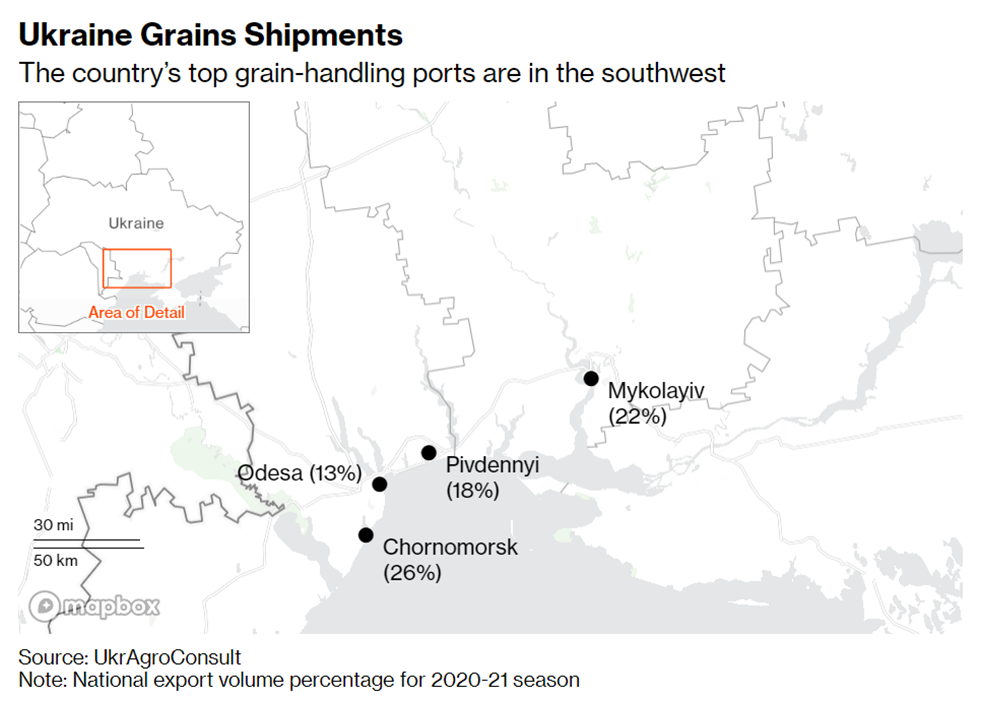

May 27 Update: Bloomberg offers a concise update on Black Sea flow options for grain, including the following map. Constanta Romania is about 260 miles by road or rail south of Chornomorsk (more and more). S&P Global also reports on potential social instability related to food price increases. (More channel options in this very helpful May 29 report by Bloomberg. The report includes, “For now, the most realistic solution remains Romania, Constanta and the Sulina Canal that links the Black Sea with the Danube.”) (Related S&P report on sunflower oil.)

May 29 Update: The Financial Times reports on a Saturday phone call: “Putin, Scholz and Macron discussed whether a negotiated solution could be found to open Odesa to allow grain exports to leave Ukraine, according to an Elysée briefing after the call. The French and German leaders “noted the Russian president’s promise to allow ships to access the port to export grain without it being used militarily by Russia — if the port was demined in advance”, according to the briefing. Berlin said the call lasted 80 minutes and was “devoted to Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine and efforts to end it”. These negotiations with Putin are not supported by all European leaders (more and more).