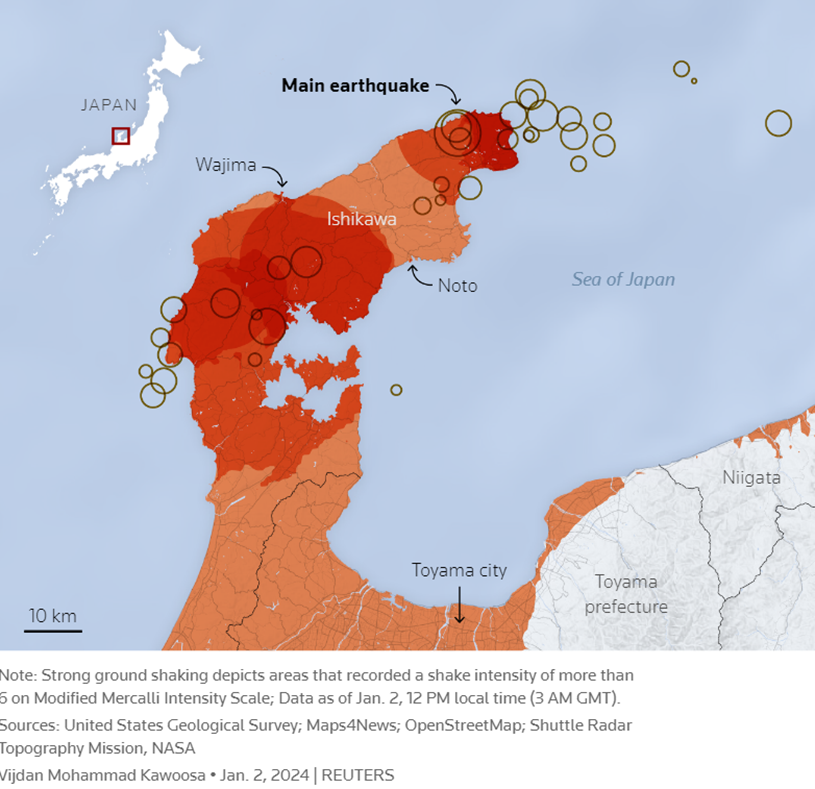

On New Year’s Day the Noto Peninsula on the west coast of Japan experienced a significant earthquake. The US Geological Survey reported a Magnitude 7.5 quake. The main quake has been followed by more than 1500 aftershocks including one M6.4 and more than a dozen between M5 and M6. Today, February 6, for the first time since, all schools in the quake zone have resumed operation.

According to Ishikawa Prefecture, the quake resulted in 240 deaths, more than 1200 injuries, and at least 28,756 residential structures are now uninhabitable. One month after the earthquake more than 14,000 persons remain in 551 evacuation centers. Before the earthquake the population of the Noto Peninsula was estimated at roughly 350,000. (More and more.)

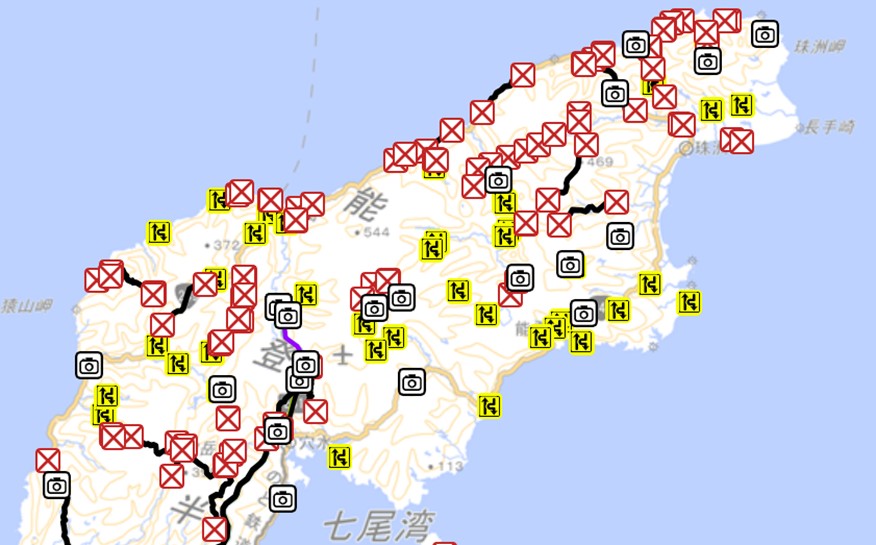

As the current map below indicates, the transportation network — especially on the north end of the peninsula nearest the epicenter — was (and continues to be) seriously disrupted in many places (here and here). Upstream supply chain capacity was not seriously impacted in nearby urban Kanazawa (465,000 persons) or Toyama (418,000 persons). Only about 150 miles away, seismic activity had no impact on the capacity organized around 2.3 million in metro Nagoya. Preexisting south-north flows using the Tōkai-Hokuriku Expressway were increased.

But this robust upstream capacity was detached from downstream demand by midstream transportation constraints. On January 5, I responded to some diagnostic questions with the following:

There are nodes of urgent need and nodes of available supply with very disrupted, diminished links in-between. The situation is mostly explained by damage/destruction of the road network in closest proximity to seismic epicenter(s). Given the innate limitations of the Noto peninsula and its landslide propensity, multiple chokepoints will not be quickly reopened, despite Japan’s well-practiced expertise in post-seismic road repair (here and here). The Asahi Shimbun reports (my rough translation): “Since large trucks cannot enter the Oku-Noto area due to damaged roads, light trucks are using a relay system to transport relief supplies such as water and food. With roads cut off by landslides , marine transportation has begun, but in the case of Suzu, the weather is bad and the water along the coast is shallow, making it difficult for Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force ships to dock.” Yesterday the military used amphibious landing craft to deploy heavy equipment and some shelf-stable meals into hard-hit Wajima City. But neither volumes nor velocity are sufficient to fulfill increasingly urgent human needs. It is very tough to reestablish sufficient flows without the recovery of preexisting flow capacity — which in this case consists of a channel involving surface roads, trucks, and truckers.

While this may sound/seem obvious, there is a persistent tendency to discount how much an effective emergency response depends on commercial flows (almost always involving many trucks) — especially with a six figure population of survivors and even more when dealing with potentially catastrophic impacts. Japan has more experience with this reality than most and there is still a stubborn focus on volume and velocity of relief supplies in place of commercial flows. It is not a competition. Both will always be needed.

Response to the Noto Peninsula earthquake did demonstrate lessons-learned from the 2011 Triple Disaster. Then commercial flows were actively suppressed for at least ten days. Last month commercial trucks — and even mobile retail services — were deployed quickly. Within 72 hours most convenience stores were open and supplies were being surged into the impact area. This included some so-called “Push Mode Support” procured by the national government being delivered by major manufacturers, distributors, and retailers using their own transportation assets (here and here).

Several hot washes on Noto have already been undertaken (here and here). Serious after-actions will eventually be done. One of the most important strategic issues is to consider what our experience in this less populated, rather peripheral place tells us about what will be necessary when a similar force envelops ten-times the population and the high capacity supply chains embedded in and near the very hard-hit place? I expect that what we will see is profound and urgent downstream demand, deeply diminished midstream flow capacity, and upstream push capacity flat on its back — unless we take appropriate action today, tomorrow, and everyday between now and then.