From time to time, most recently on May 2, this blog has given attention to Supply- and Demand-Driven Contributions to Annualized Monthly Headline PCE Inflation by staff with the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Yesterday an extended review and update was published by the FRBSF. Below are a few quotes to encourage you to read the full report here.

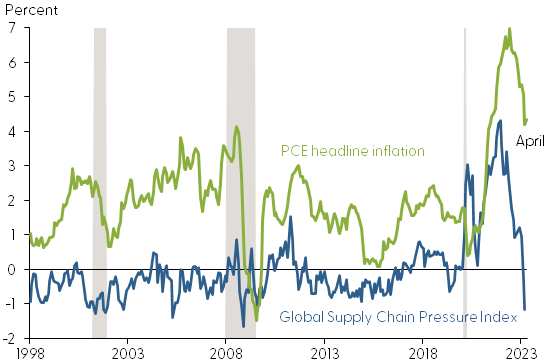

As suggested by the chart below, this analysis draws on two other Federal Reserve statistical products: Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) and the Global Supply Chain Pressure Index (GSCPI). Is there a statistically valid relationship and, if so, what does this relationship tell us?

Supply chain disruptions increase input costs and raise the public’s expectations for higher prices. We estimate that these effects contributed about 60% of the above-trend run-up of headline inflation in 2021 and 2022...

Since supply chain disruptions directly constrain supplies of traded goods, with only indirect effects on services, one would expect a GSCPI shock to boost goods price inflation more than overall inflation. This is the case in our model results. We find that a one standard deviation shock to the GSCPI raises PCE goods inflation by up to 1.5 percentage points relative to the pre-shock level, about three times the peak effect on overall inflation…

Disruptions to global supply chains are often associated with surges in commodity prices. Studies have shown that people’s inflation expectations—especially for short-term, one-year ahead inflation—are sensitive to commodity price fluctuations… A tightening of supply chain constraints can raise imported goods prices, which are then passed through to consumer prices… In response to supply chain disruptions, businesses would pass increases in intermediate input costs through to consumer prices...

… as costs move further along the production chain, from initial inputs to intermediate goods, PPI inflation becomes less sensitive to a GSCPI shock. The effects of the shock on final consumer goods inflation are even more muted…

The Federal Reserve is mostly interested in price stability and maximum sustainable employment. I am mostly interested in flows (and frictions) of demand and supply. What I indirectly perceive in the FRBSF analysis is how seriously disrupted demand — and suppliers’ (over?) response to such disruptions (e.g., 2020) — can spawn a stubborn feedback loop that amplifies and extends both demand and supply disruptions (e.g., 2021 and the first half of 2022). How many times do we have to play the Beer Game before we have a disciplined confidence in the parameters of demand vis-à-vis core production/ distribution capacity?