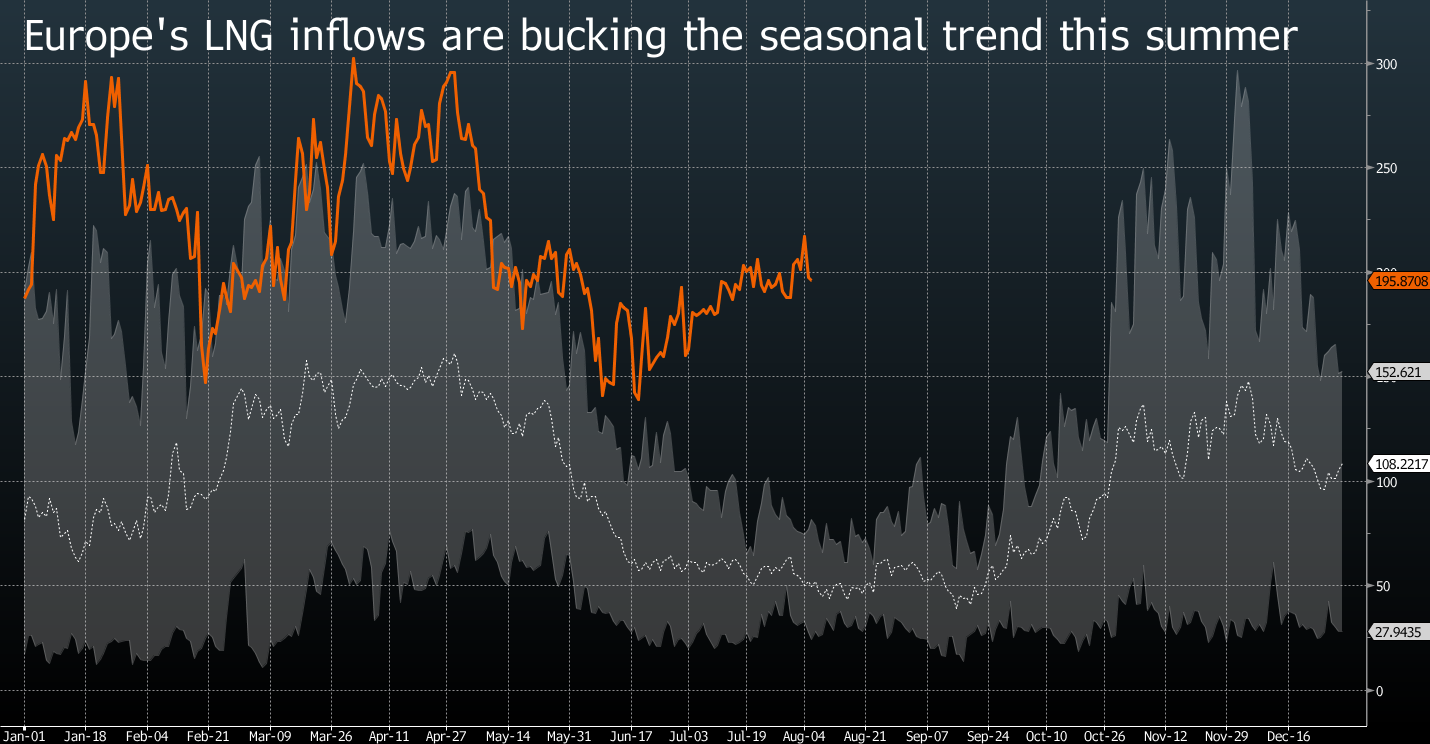

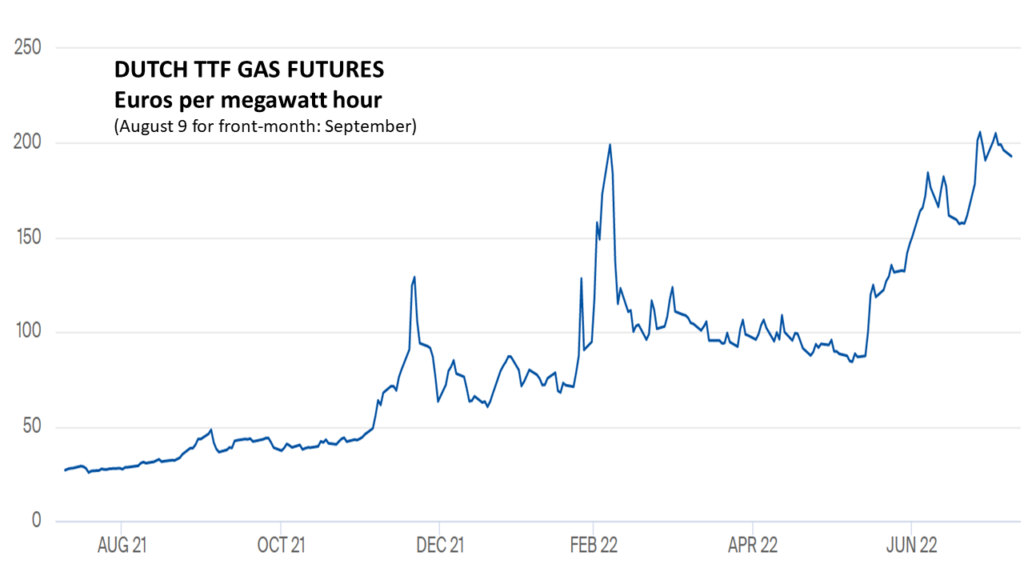

[Updates below] Natural gas storage facilities in the European Union are now over seventy percent full. Inflows have been well above normal for Spring/Summer since the end of May (see chart below). France is at over 80 percent, Italy about three-quarters, Germany at the EU average. Austria, Hungary, and Latvia are closer to 55 percent (more). The (very high) natural gas benchmark price at Rotterdam has eased just a bit (see chart below). High temperatures this week — increasing electricity demand — will not allow much near-term progress. Off-season natural gas demand (and prices) could also surge if coal deliveries to power plants along European rivers are disrupted by drought and falling river levels. Winter is certainly not the only threat. But winter is surely coming. Very few grasshoppers are seen in European capitals this year.

August 10 Update: According to Bloomberg, “The Rhine River is to become virtually impassable at a key waypoint in Germany, as shallow water chokes off shipments of energy products and other industrial commodities along one of Europe’s most important waterways. The marker at Kaub, west of Frankfurt, is forecast to drop to the critical depth of 40 centimeters (just under 16 inches) early on Aug. 12, falling to 38 cm later in the day, according to the German Federal Waterways and Shipping Administration. At that level, barges that haul everything from diesel to coal are effectively unable to transit the river.” (More and more) On August 11 the Wall Street Journal reports on reduced water levels for European rivers other than the Rhine.

August 12 Update: S&P quotes a German gas-trader, “Even with full storages it could get difficult if winter gets cold or Russia cuts further.” In the same report other market insiders argue, “We won’t run out… no commodity ever runs out… it’s all a matter of pricing now… the gas shortage will just be replaced with extreme price highs.” Another European gas trader, also highly skeptical that Europe will run out of gas, said that “as storages continue to fill, the market should start realizing that the winter is looking less and less scary… as long as it doesn’t turn out very cold.” During an August 11 news conference, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz said, “We’ll be in a situation . . . where it might be expensive to get gas, because of the state of the global market, but we will always get enough.” (more and more).

August 19 Update: Over the last nine days the Dutch TTF LNG price has surged almost one-quarter higher. Rhine River water levels are not the only cause, but are contributing . S&P provides the following infographic on the near-term economic reverberations of Rhine River reductions in flow. For a longer-term view, please see Helen Thompson’s assessment in today’s Financial Times. She foresees reduced energy access and sustained higher prices resulting in very tough economic and geo-political choices.