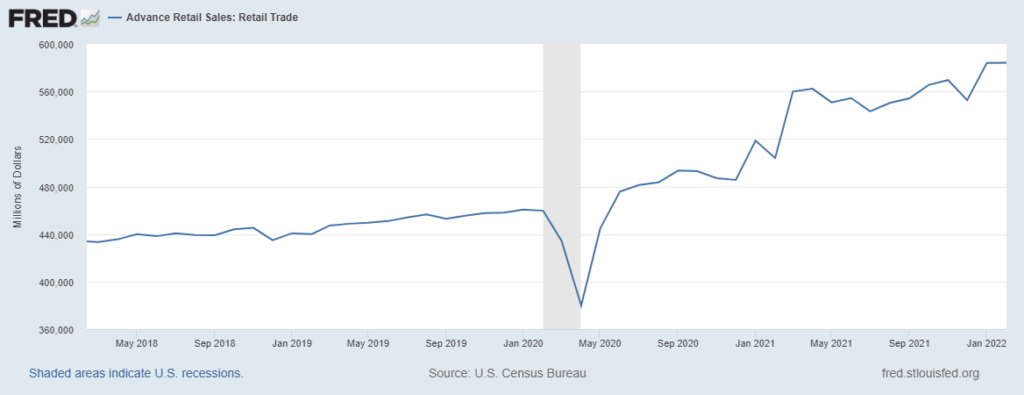

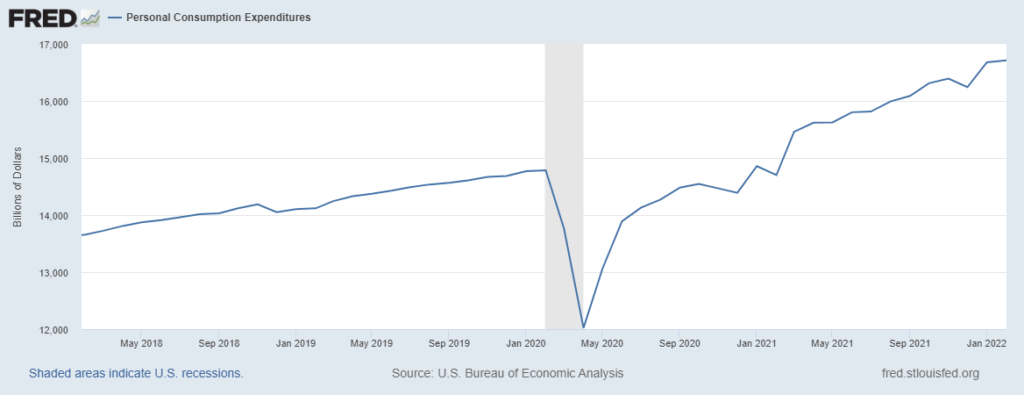

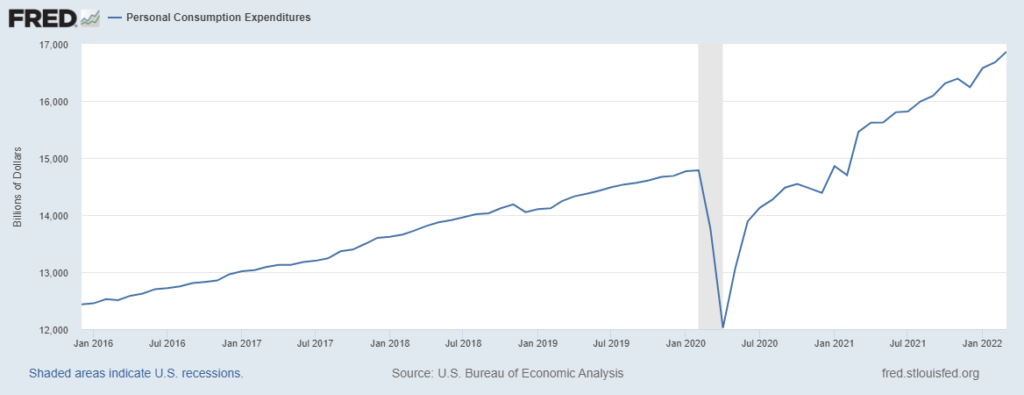

According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, March US Personal Consumption Expenditures continued to grow (see chart below). Not adjusted for inflation, Americans are spending more than ever before. The rate of expenditure growth is a bit less torrid than one year ago. The purchase mix is also much closer to pre-pandemic patterns: services, entertainment, travel, and eating out are back. Demand for “stuff” has softened (and some stuff is still and will be hard to get, see here and here).

Strong US employment and wage growth are supporting consumption. Higher earning Americans can also draw down savings accumulated from non-spending and higher incomes in 2020 and 2021. All consumers are paying somewhat more because of price increases, especially for food and fuel. The Personal Saving Rate for current cash-flow is now about 15 percent lower than decade-long pre-pandemic averages.

Supply chain implications: The retreat from even more stuff and advance on services is reducing friction in goods movement. For example, Amazon has reported slower revenue growth for first quarter 2022 and single digit growth ahead. On Thursday Amazon’s CEO said,

Today, as we’re no longer chasing physical or staffing capacity, our teams are squarely focused on improving productivity and cost efficiencies throughout our fulfillment network. We know how to do this and have done it before. This may take some time, particularly as we work through ongoing inflationary and supply chain pressures, but we see encouraging progress on a number of customer experience dimensions, including delivery speed performance as we’re now approaching levels not seen since the months immediately preceding the pandemic in early 2020.

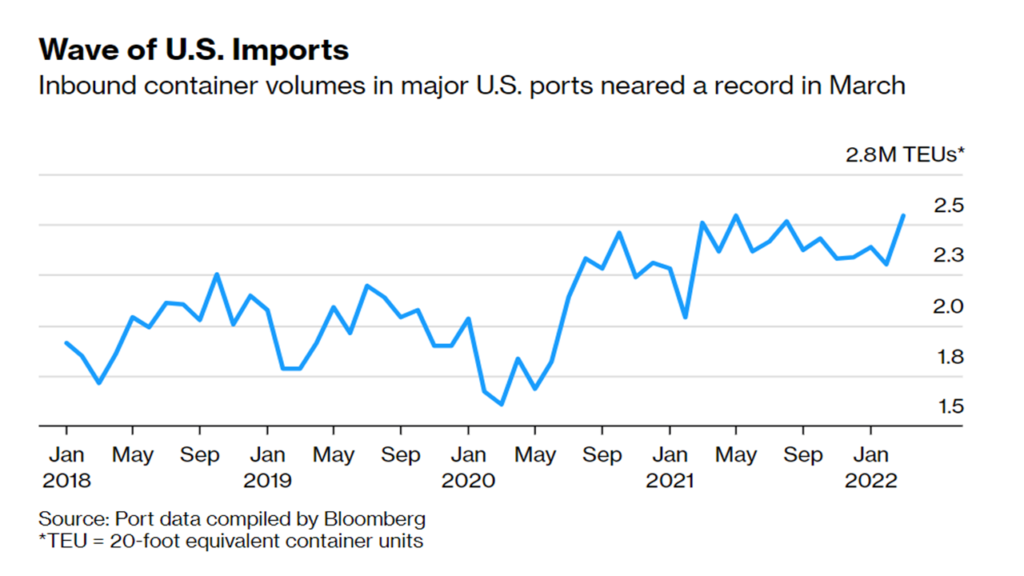

According to many March results, freight flows were (are?) evening out. North American ports are much less congested. Several indicators suggest last month’s freight volumes and expenditures were consistent with 2018 and 2019 (more). After two years of extreme volatility, 2022’s first quarter saw equilibrium gradually resurfacing in many sectors of demand and supply.

But on February 24 Russia invaded Ukraine. By mid-March various sanctions were complicating flows of Russia’s energy, food, and metals. Military measures seriously disrupted flows of Ukraine’s agricultural products. Global prices for food and fuel (and related) increased accordingly. Complications in these flows have proliferated since mid-March. US diesel prices are flirting with all-time highs.

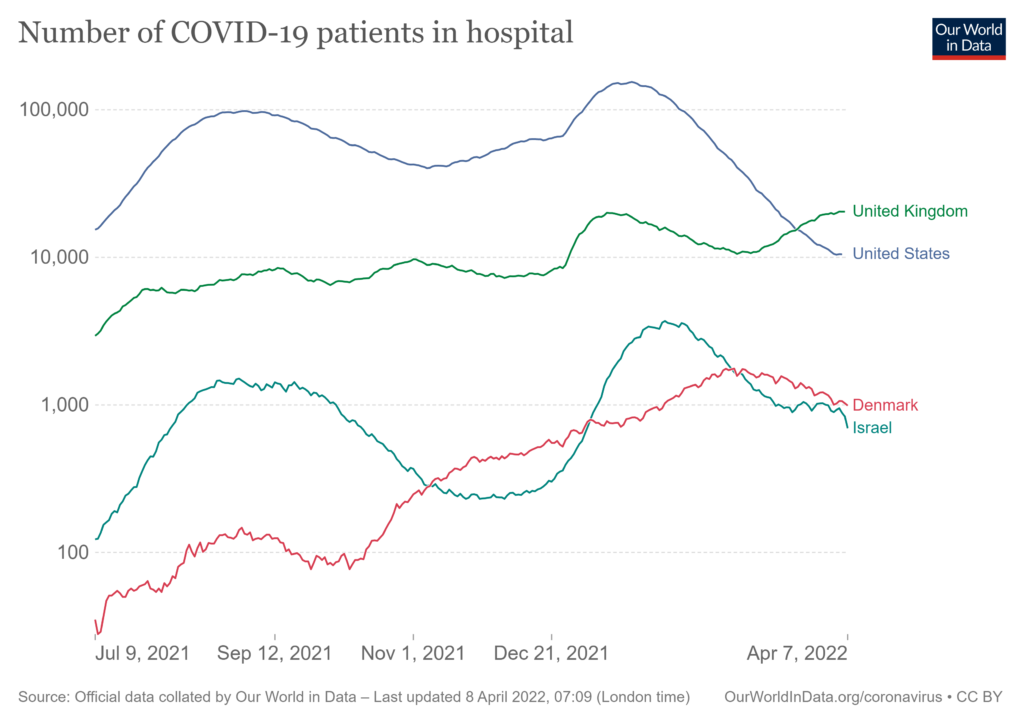

On April 1 Shanghai was locked-down. By mid-April, by one estimate, more than 40 percent of China’s economy was seriously disrupted by the attempt to contain covid. The demand shock in China is undeniable. The potential supply shock for the rest of the world is deeply worrisome. As previously noted (here and here), I am part of a distinct minority who still, tentatively, discern it is possible that China’s outbound flows — plus adaptation elsewhere — will mostly match broad-based global demand for manufactured goods.

But apparently not for many Apple products. Thursday Tim Cook, Apple’s CEO, told financial analysts:

… looking ahead, we see two causes of supply constraints. One is the COVID-related disruptions, and there’s the industrywide silicon shortages that will continue. We’ve estimated the constraints to be in the range of $4 billion to $8 billion. And if you — these constraints are primarily centered around the Shanghai corridor. And the — on a positive front, almost all of the affected final assembly factories have now restarted. And so, the range, the $4 billion to $8 billion range, reflects various ramps of getting back up and running. We’re also encouraged that the COVID case count that’s been reported in Shanghai has decreased over the last few days. And so, there’s some reason for optimism there. Then answering a related question, Mr. Cook added, In this business, you don’t want to hold a ton of inventory. And so, you want to work on cycle times and so forth to do things very quickly and take strategic inventory in places where you need to buffer for interruptions and so forth. And so, we’re constantly thinking about where those places are. In today’s world, it’s not really possible for us to have buffer on silicon. And so, today, silicon rolls off the fab and it’s into a final assembly plant very, very quickly, and we try to make that as shorter time as possible.

Apple is absolutely not alone. Recently at FreightWaves Craig Fuller outlined what he perceives is not happening upstream from China’s ports:

The loss of trucking capacity in China means that raw materials and components can’t get from the ports to factories and finished goods can’t leave the factories to the ports to be put on ships for export. The temporary blip (dead cat bounce) was likely containers that were already in the queue at the port prior to the lockdowns. Since factories can’t receive new components or raw materials, they will also stop operating once their supplies are exhausted. Supply chains involve large webs of suppliers that are interconnected and just because one supplier is online does not mean that other suppliers are. Once they shut down, it will take much longer to bring them up to full productivity. According to SONAR’s ocean intelligence dashboard, it currently takes 27 days for a vessel to travel from a Chinese port to a U.S. port. Since the volume of containers from China to the U.S. started its drop on April 6, it will likely be May 3 before U.S. ports experience a drop in volume.

Combine Tim Cook’s comments with Craig Fuller’s analysis and there is good cause for outbound flows from China anticipating rocky shoals ahead. How low might flow go? How fast?

Tim says Shanghai production is ramping up (so do others). So-far total outbound flows from China are more up-and-down like a roller coaster than spinning down like a water slide. Both Europe and the United States over-reacted to a much more complete stop in flows from China in February 2020. The prospect of lost flows became a self-fulfilling — and self-subverting — prophecy. Transpacific container spot rates have recently been stable (more). Some insiders even claim flows from China are about to surge. I also notice that real (inflation adjusted) US individual disposable income decreased 0.4 percent in March while our purchases of goods declined 0.5 percent and purchases of services increased 0.6 percent. Americans are still buying plenty, but don’t want as much from China now as during most of 2021.

I also watch, a bit amazed, as Russia’s oil essentially flows uphill toward persistent demand (more). I notice Ukraine’s grain using every available crack and crevice to connect with desperate demand. There are all sorts of serious problems. But again and again, I seem to see whither goest demand, so goest supply.

April 30 Update: China’s official print for the April Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) confirms the slowdown in production and domestic consumption. According to Reuters: “China’s factory activity contracted at a steeper pace in April, as widespread COVID-19 lockdowns curbed production and disrupted supply chains, an official survey showed on Saturday. The official manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) fell to 47.4 in April from 49.5 in March, for a second straight month of contraction, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) said. The 50-point mark separates contraction from growth on a monthly basis.” Perhaps I protest too much, but it seems to me worth noting that the manufacturing element in the index remains well-above 2020’s bottom and even above current factory orders (export or not). China’s domestic demand has been decimated. Demand for China’s goods in much of the world is cooling. Even US demand, still stronger than most, has lost a couple of degrees of friction’s heat (more ).

The argument about what comes first — supply or demand? — can become (like chicken or egg) a definitional rabbit hole. Of course, both factors matter. Disrupted, congested, and delayed outbound flows from a major upstream node (even more: a dense cluster) will frustrate demand. Long-term, wide-area, extreme demand surges (or destruction) will seriously stress supply capacities. Either can cause disequilibrium. Over the last two years we have often suffered both. Today there is increasing evidence of less extreme demand. To the extent effectual demand continues to more steadily pull, this will help sources of supply to push more consistently… to the extent war, plague, and calamity allow.