US case counts are increasing in more places than not, with double-digit increases in Delaware, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Michigan. The national average for hospitalizations has, according to some sources, reversed its recent declines. The number of deaths-per-day has increased by more than ten percent in Delaware, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Colorado, Virginia, New York, Connecticut, and Tennessee. Since mid- February, Americans are circulating more widely and with more people. This gives the virus more opportunities. The virus has no self-restraint. Most humans can choose to be self-restrained. Our actual behavior is too often the result of not choosing.

Month: March 2021

Learning (Re-learning?)

A journalist has asked several to write — in 300 words or less — what the pandemic has taught us about supply chains. Here is how I responded:

What did the pandemic teach you about supply chains?

The pandemic has (so far) mostly emphasized essential characteristics that tend to be taken for granted in less challenging contexts.

The pandemic taught me that organizing around demand is fundamental. Where and when manufacturers, carriers, customers, and even competitors collaborate to calibrate around demand, flows can adjust to new needs much more quickly. Where demand is neglected or miscalculated or just not known, supply misses the mark more and more, troubles accumulate, velocity is reduced, so volumes are not maximized to fulfill demand.

The pandemic taught me that where the scope and scale of demand can be confirmed (and effectual demand continued over time), extraordinary creativity is possible in terms of streamlining and maximizing existing production capacity (much more than I expected). But I also was reminded that production capacity is constrained by access to capital, stubborn issues of time, and — especially –perceptions of sustained future demand.

The pandemic taught me that robust, diverse, agile freight systems can multiply and divide every other supply chain capacity. When freight assets — surface or maritime or air in whatever mode — are most flexible, then the whole supply chain is more resilient. Persistent freight problems will undo every other advantage and double any other disadvantage. When and where freight channels are flowing, problems with production or demand or whatever can usually be mitigated.

The pandemic taught me that humans — even smart, self-aware, and alert humans — tend to discount the likelihood of any major shift in prior experience, even when the evidence is obvious and racing toward us. Probably related: the pandemic taught me that smart, self-aware, and alert humans tend to focus on well-defined problems or opportunities and tend to discount ill-defined issues, no matter how potentially consequential. (Yikes!)

The Ever Given Analogy

The huge container ship blocking the busy Suez Canal is, perhaps, the best analogy ever given for innate tensions — and potential frictions — at the core of contemporary demand and supply networks.

Ever Given was enroute from Tanjung Pelebas, Malaysia to Rotterdam carrying about 20,000 TEU. Not long after entering the Suez Canal high winds drove the ship’s bow into the east side of the canal. It has now been stuck for five days. “Each day of blockage disrupts more than $9 billion worth of goods, according to Lloyd’s List, which translates to about $400 million per hour” (more).

The ship’s beam (width) is precisely as big as possible to still use the canal. This maximizes potential volume for the highest seaborne velocity between East Asia and Western Europe. A large load allows maritime carriers to prorate their costs (and profits) over more units of throughput. This is usually a win-win for shipper, carrier, and consumer. Except when a pandemic shuts down most flows. Except later in the same pandemic when surging consumer demand exceeds current shipping capacity. Except when shipping capacity is compromised by too many containers being left outside current circulation.

Concentrations typically speed and smooth exchange within and between concentrations, allowing more to be done with less more quickly. Supply optimized to demand reduces waste, costs, and can allow lower prices.

Concentrations also aggregate risk, especially when and where multiple concentrations intersect, as at the Suez Canal where twelve percent of planetary trade and thirty percent of global container flows line-up to be threaded between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean. Concentrations of production, demand, and conveyance coincide in a single thin, shallow trench. For the moment these concentrations have collided and highly optimized flow is paused.

Not all flows have stopped. There are alternative routes that require more time and cost. But already congested ports are more crowded. Insufficient maritime capacity is further constrained. Fulfilling late-stage pandemic demand will be delayed. Post-pandemic economic recovery is further complicated. Friction accrues. Flows slow. The frenetic energies of optimized demand and supply networks reverse into an increased incidence of commercial failure. Networks furiously adapt to resist this conflation of negative feedbacks becoming a conflagration of economic collapse.

UPDATE ON MONDAY, MARCH 29: The Ever Given has been freed

Has anybody ever given the ocean a medal?

Who of the poets equals the music of the sea?

And where is a symbol of the people

unless it is the sea?

From The People, Yes! by Carl Sandberg

Three Data Indicators

The current situation in Europe, India, and Brazil each (and all) demonstrate the continuing risk of another surge in disease.

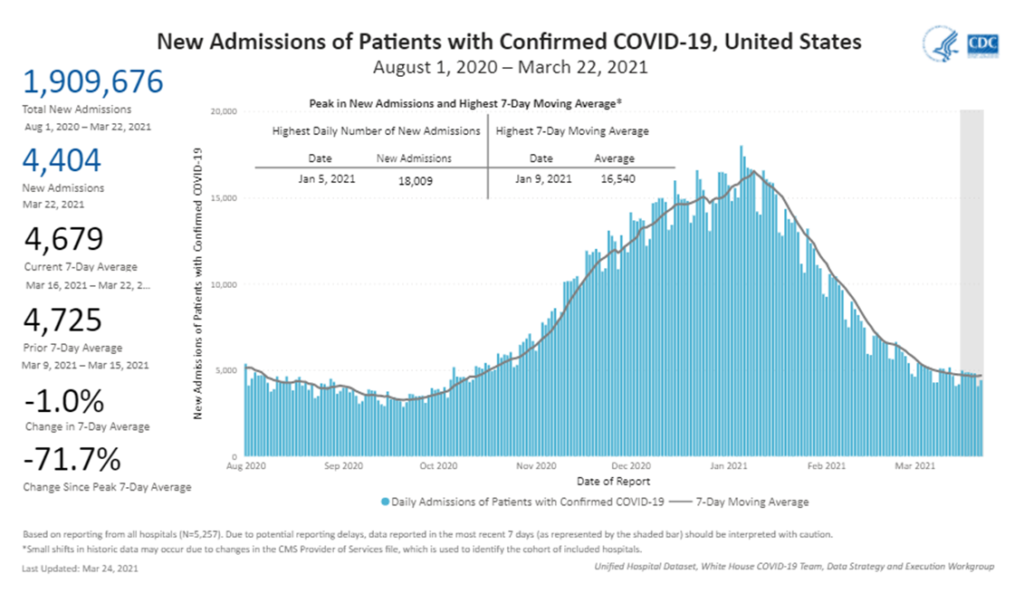

US hospital admissions related to covid continue to ease. This indicator is our most rigorous signal of covid’s “demand-pull” on the healthcare system. In my judgment fatalities, while even more rigorous, signal demand cessation or, perhaps, demand intensity.

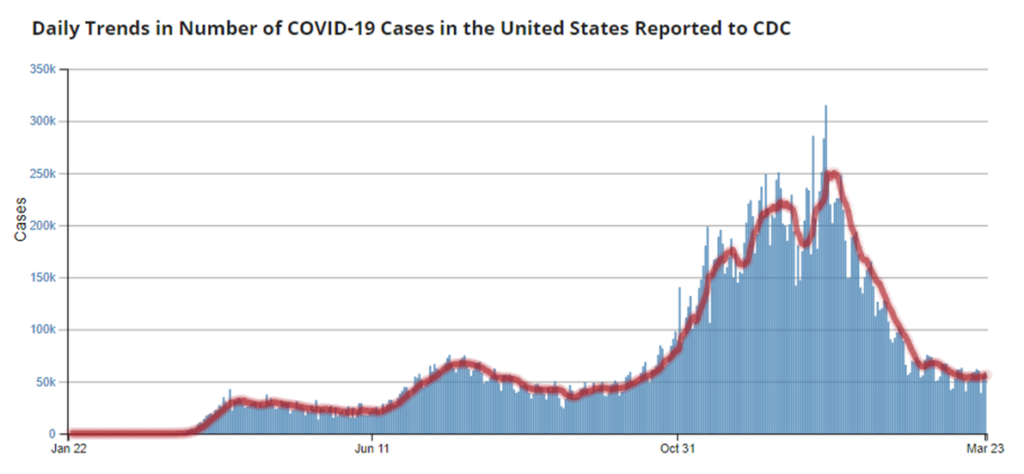

US case counts are suggestive and worth watching, but substantially undercount actual “consumption” of covid.

Especially in comparison with much of Europe, India, and Brazil, these US data indicators are clearly more positive. But current case counts (at least in the US with its anemic testing/tracing system) typically lag viral flows by a matter of several days. New hospital admissions typically reflect disease conditions two or three weeks prior. In either case, once case counts and hospitalizations are surging it is too late to stop the surge. Post-hoc we can only contain.

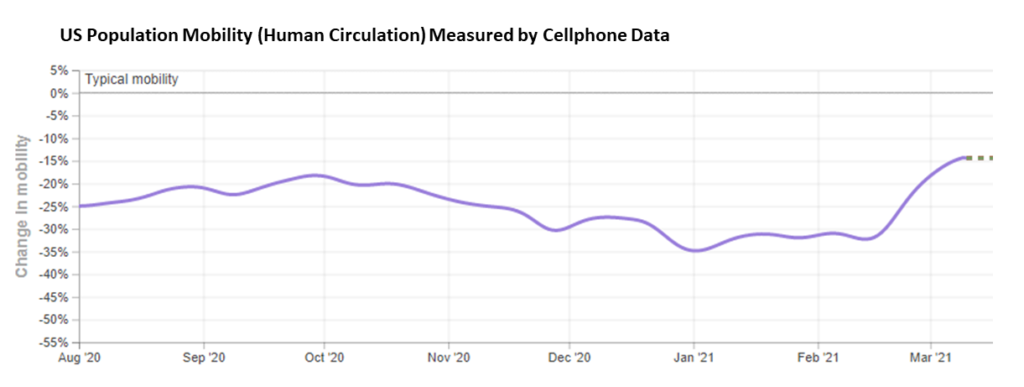

Searching for an ex ante indicator, my best — if very rough — tool has been cell phone mobility data. It has seemed to me (but much more diligent data analysis is needed) that when and where human circulation has remained at three-quarters pre-pandemic levels, covid has been much more effectively demand-managed (two-thirds is even better, the ROI beyond 2/3s has, so far, seemed negligible).

So… from a supply chain perspective, US behavior over the last three weeks is cause for concern. Can US vaccination rates mitigate the risk resulting from this increased circulation? I am much more confident that vaccinations combined with ten percent less human circulation (or even less) than shown below would avoid another demand-surge on the healthcare system in mid-to-late April.

More Vigilance

According to the Los Angeles Times, recent CDC analyses assessed two contending variants of the coronavirus. The B.1.427./B.1.429 variant, first identified in California, is now prevalent in that state and spreading further. But outside California, the B.1.1.7 variant, first identified in the United Kingdom, is claiming a much higher percentage of new transmissions.

A study published on March 15 in the British journal Nature concludes, “we estimate a 61% (42–82%) higher hazard of death associated with B.1.1.7. Our analysis suggests that B.1.1.7 is not only more transmissible than preexisting SARS-CoV-2 variants, but may also cause more severe illness.”

While overall US case counts, hospitalizations, and deaths continue to decline, there are places going the opposite direction. In twenty-three states, the one week average of newly reported cases is higher than than the two-week average. As of March 18, Oregon daily case counts are up 8.1 percent, Vermont is up 9.9 percent, and Utah is up 15.4 percent. Daily fatalities have recently increased more than ten percent in both Oregon and Utah. There is concern that as B.1.1.7 claims more “market share”, that the United State could follow Europe into yet another wave of disease (more and more).

Vaccination rates are increasing in most of the US. Roughly three-quarters of US residents are regularly using face-coverings in public. According to credible indicators, however, US population mobility has substantially increased since mid-February. On Valentines Day Americans were circulating about one-third less than usual. By March 10 we were only 14 percent below pre-pandemic travel patterns. This is much more than just Spring Break trips. This suggests a change in behavior by millions.

Vigilance requires using every tool we’ve got. One-quarter to one-third self-restraint now will avoid thousands of hospitalizations — and two-thirds to three-quarters enforced restraint — later.

Resilience Principles and Practice

A recent White House Executive Order notes, “The United States needs resilient, diverse, and secure supply chains to ensure our economic prosperity and national security.”

Supply chain risks can be reduced or transferred, but many risks cannot be avoided. For demand and supply networks to fulfill their purposes, a wide range of insecurities are innate to purpose and function. Supply chains cannot be fully secured and remain supply chains.

For some purposes it is possible to create highly secure manufacturing capacity, transportation modalities, and effective deployment of technologies and related services. But this process is unlikely to benefit from high velocity, cost-amortized-over-volume, self-actualizing, demand-fulfilling networks, which are among the key characteristics that differentiate “supply chains” from other less efficient forms of supplying demand.

In many ways, supply chains can be resilient and diverse or we can create secure means of supply. When we create secure processes, we should explicitly recognize related constraints. In some contexts, more security is entirely justified, but it will always travel with higher costs, less agility, and usually with reduced speed.

We should also explicitly acknowledge implications of insecurity in demand and supply networks. Given the innate insecurity of supply chains, systemic resilience is an essential characteristic for the most human-critical and nation-critical supply chains. Supply Chain Risk Management, strategically conceived, is primarily the cultivation of Supply Chain Resilience. There will be failures. Recurring, relatively small failures typically characterize the most resilient networks. As high volume, high velocity networks are optimized, the circuit-breaking characteristics of small failures can often be squeezed out. Over time an increased risk of cascading, large-scale failures can be — unintentionally — built-into demand and supply networks.

Supply Chain Risk Management is aware of this tendency, actively monitors flows for fitness and systemic risk, takes action to mitigate risk in advance, and prepares to effectively contain and recover from catastrophic cascades.

Five Core Principles of Supply Chain Resilience

Supply Chain Risk Management advances Supply Chain Resilience by cultivating five core principles:

Principle: Resilient demand and supply networks are diverse, involving many different places, people, processes, forms of competition, forms of collaboration, varied conveyances, widely distributed sources, multiple pathways for demand and supply. Concentrations (hourglass structures) facilitate volume, velocity, and therefore robustness (see below) but over-concentration can amplify systemic vulnerability. Practice: Observation: identify and map sources, links, relationships, proportional flows, and current/recent deficiencies. Orientation: Ecosystem flow (more) and fitness (contrasted to any particular species). Decision: Is diversity being fostered or impeded? Where is diversity most at risk? Where is less diversity most consequential? Why? Action: Enhance diversity.

Principle: Resilient demand and supply networks feature abundant feedback. Demand signaling is well-facilitated across the network. Major market conditions (e.g. input costs, supply availability, freight market performance, transportation conditions, etc.) are known. Major players know each other and often communicate together either directly or through many trusted intermediaries. Practice: Observation: identify and map feedback loops. Orientation: Ecosystem flow and fitness (contrasted to any particular species). Decision: Is feedback being fostered or impeded? Where is feedback most anemic? Why? Where is this anemia most consequential? Action: Enhance feedback.

Principle: Resilient demand and supply networks feature wide-spread (diverse and feedback informed) agile self-organization. A wide-range of individual, largely independent players have easy access to the network, participate in feedback loops, and are able to explore — and exploit — network fluctuations on their own decision and at their own risk. Practice: Observation: identify and map indicators of self-organization. Orientation: Ecosystem flow and fitness (contrasted to any particular species). Decision: Is self-organization being fostered or impeded? Where is self-organization least prevalent? Why? Where is lack of self-organization most consequential? Action: Enhance self-organization.

Principle: Resilient demand and supply networks feature agile and effective adaptation. When many diverse players are constantly signaling each other regarding network shifts and each player has significant freedom to explore and exploit these shifts, then myriad individual choices will filter failures and successes and in this way shift the entire network toward more effective behaviors. Practice: Observation: identify and map adaptive behaviors. Orientation: Ecosystem flow and fitness (contrasted to any particular species). Decision: Is adaptation being fostered or impeded? Where or when is adaptation less common? Why? Where or when is lack-of-adaptation most consequential? Action: Enhance adaptation.

Principle: Resilient demand and supply networks are robust: Resilience can deeply abide in very small, isolated (secure?) contexts. But the more connected the context, the more resilience depends on robust scope and scale. Large systems — that are also diverse, feedback abundant, self-organizing, and adapting — will resist fundamental (or catastrophic) change, even while constantly changing through small failures and accumulated innovation. Practice: Observation: identify and map scope and scale. Measure pressure-levels of flow across the network. Orientation: Ecosystem flow and fitness (contrasted to any particular species). Decision: Are scope and scale growing or diminishing? Integrating or fragmenting? Are flows being widely facilitated or are some channels and sections being shed? Why? Where or when does robustness seem to compete with resilience? Where or when does robustness reinforce resilience? Action: Enhance resilience.

Operationalization of Supply Chain Resilience (or Practice Supply Chain Risk Management at the Ecosystem Level)

The matrix suggested by the preceding is so complex and dynamic that it is not currently possible to identify and map anything close to full flows. Even meaningful snapshots are difficult and treacherous. Given current conceptual and technological capabilities it is helpful to set meaningful boundaries for engagement. One of the most important outcomes of the six assessments set out in the Executive Order could be specific targets for operational engagement. While there are clearly better or worse targets, the issue is not so much finding the most consequential target(s) as choosing a plausible set of targets with which to begin data-gathering, relationship-building, analysis, and synthesis consistent with the five core principles.

Several substantive and structural recommendations for follow-on to the EO tasks have emerged. Here are two: BENS and CBA/CSCMP. There will be more. Many of these operational recommendations are coherent with the five core principles identified above. Many of the approaches offered so far are government-centric. Many of these recommendations would assist the US government play a more constructive role in Supply Chain Resilience. But any government-centric role will, on its own, fail to engage many risks and opportunities for Supply Chain Resilience. Demand and supply networks are not inherently governmental. In her 2009 Nobel Prize Lecture Elinor Ostrom said:

Most modern economic theory describes a world presided over by a government (not, significantly, by governments), and sees this world through the government’s eyes. The government is supposed to have the responsibility, the will and the power to restructure society in whatever way maximizes social welfare; like the US Cavalry in a good Western, the government stands ready to rush to the rescue whenever the market ‘fails’, and the economist’s job is to advise it on when and how to do so. Private individuals, in contrast, are credited with little or no ability to solve collective problems among themselves. This makes for a distorted view of some important economic and political issues.

Such a distorted angle on reality will fail to advance Supply Chain Resilience. A stubborn adherence to this distorted angle actively threatens Supply Chain Resilience. In addition to the government reforms outlined by others, there is a need for a whole-of-nation approach to developing Supply Chain Resilience. This would most likely be achieved through a Congressional chartering of a public-benefit corporation that would, consistent with the five core principles:

- Conduct data-gathering, relationship-building, analysis, and synthesis focused on the ecosystem level of demand and supply networks.

- Convene and facilitate meaningful and regular feedback regarding flows and fitness of demand and supply networks.

- Recommend and when possible facilitate voluntary mitigation and preparedness activities to advance Supply Chain Resilience

Vigilance

Italy has toughened Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions as infection rates increased ten-percent over last week. A sharp increase in German case counts has also been seen. ICU beds are close to full in Brazil. US coronavirus daily case counts and covid-19 death-rates continue to decline. (Hospitalizations are now more difficult to track). Variants are more prevalent in the United States, but not — yet — the source of a significant surge in disease and related demands on the US healthcare system.

Better Days?

As far as I can tell, the current context for covid-19 in the United States is constrained and becoming more constrained. Our current condition is better than I expected eight weeks ago or even two weeks ago.

Given the current status of virus mutations, reasonable projections for vaccination rates, and continued Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions, it now appears likely most of the US can avoid another deadly contagious spike. Each additional day that covid deaths and hospitalizations decline, the less risk of resurgence.

Given past behavior by the coronavirus, my concern was not misplaced — and vigilance is justified. The virus will continue to evolve and will exploit any openings we provide.

But here’s an assessment of what has happened (and not happened) since late 2020.

The variants appearing in the United States have — so far — not been as virulent as I feared. While the variants are certainly spreading, there has not (yet) been the rapid increase in disease seen in other places. There is also accumulating evidence that current vaccines are largely effective suppressing transmission of known variants. So, as the number of Americans vaccinated continues to advance, the variant risk should decline. Well into late February I was worried that the US coronavirus testing process might be too weak to recognize a variant take-over and warn us of threats to the healthcare system. But given the continued decline in hospitalizations (more), I have finally decided that — until data demonstrate otherwise — it is reasonable to give at least as much attention to optimistic options as other options.

Further, the US population has been more self-restrained than I perceived early in the New Year. In late September US mobility was about 18 percent less than pre-pandemic. Over the final three months of 2020, mobility decreased to about one-third less than pre-pandemic — despite Halloween, Thanksgiving, and Christmas comings and goings. Over the same 90-some days use of facial coverings is estimated to have increased from about 64 percent to about 76 percent. There is now evidence that as more Americans suffered confirmed cases of covid-19, related hospitalizations, and death, millions of Americans responded by reducing their circulation and increasing prophylactic behavior. Even edging into mid-March, mobility statistics appear to be holding at about one-quarter below pre-pandemic levels.

The risk persists. We absolutely should continue to look for hot spots, especially of vaccine-resistant variants. But with reduced population circulation, individual face-to-face restraint, and with each additional vaccination, the United States is giving the virus less opportunity… and improving our future opportunities.

Francine Lacqua interviews Moderna co-founder Noubar Afeyan

This Bloomberg interview is helpful on very timely issues of vaccine development and timeless issues of creativity, organization, and leadership.

Answering Vaccine Distribution Questions

In preparation for a March 4 interview the following questions were sent ahead. To organize my own thinking, here is my written “homework.”

What does the vaccine distribution strategy look like from a supply chain perspective? i.e., How does it differ from other types of supply chains?

The US vaccine distribution strategy has been — basically still is — very supply-oriented, not demand-oriented. It is as supply-oriented as many pre-1970 wholesale markets. This is dramatically different from contemporary high volume, high velocity supply chains. Where today the biggest players compete over who can best understand — and even own — demand. US vaccine distribution has been, at best, a Sears distribution strategy… and Sears before Walmart was recognized to be an existential threat. Today supply chains are demand-driven, data-driven, fluid-dynamic networks. Vaccine distribution, in contrast, has divied up available supply and pushed it out toward counties, cities, and towns, depending on excess demand to do the rest.

In some ways this makes sense. Less than nine months ago there was no scalable production capacity for these vaccines. It was obvious initial demand was going to far exceed supply well into 2021. But as supplies have continued to expand we are beginning to see the limitations of this supply-oriented approach. By the end of June I bet we will be worried about lack of demand for available supply because of various kinds of vaccine hesitancy.

What are some of the challenges identified at the beginning of the process, for example in late 2020, before vaccines started shipping? How has the industry tackled some of these complications? For example, the low temperatures required by the Pfizer vaccine.

On August 27 the CDC asked states and others to begin planning for vaccine distribution as early as November 2020. Planning scenarios and guidance were provided, including the potential need for double-doses and ultra-cold storage. The planning scenarios were obviously, if implicitly, based on the possibility of early approvals for Moderna and Pfizer products. As it turned out, these products were the first to receive Emergency Use Authorizations, but not until mid-December.

Pfizer — already one of the most capable pharma distributors on the planet — decided to deploy its own distribution capabilities. Moderna — a much less mature enterprise — is more dependent on the US Government distribution network managed by McKesson. Both the Pfizer and Moderna distribution efforts involved a number of sub-contractors, including usual suspects like UPS and Fedex, that were involved in detailed preparations since this summer.

At the distribution level — let’s say from the filling/finishing facilities to a hand-off to each of the States — the cold-chain and other novel constraints were expensive and logistically non-trivial, but clearly within the capacity of the contractors and the US national freight network. Vaccine packages are small and uniform. Flow has increased gradually. Certainly distribution has required significant upfront investments, there have been some serious hiccups, and no doubt there have been late nights and urgent interventions. But outputs — outcomes — have largely been as planned and projected at the distribution level.

Then at the wholesale level (retrieving that pre-1970s paradigm), once the handoff to the states happened. outcomes have varied dramatically. The Pfizer vaccine began to ship on December 13. Moderna began shipping seven days later. Three weeks after flows started, we had a national Vaccine Utilization Rate of about 30 percent (more). Some states, localities, and hospital systems were moving inventory much more quickly and others were much slower. Very high demand, but only about 30 percent of available inventory was being consumed. Since mid-February our national Vaccine Utilization Rates have been above 75 percent. But variation is still significant. During the first week in March the National Vaccine Utilization Rate was over 75 percent while one state was at 68 percent and two others had broken 90 percent.

What is needed to ensure the most reliable vaccine distribution?

There are a whole host of requirements for reliable vaccine distribution, just as with any pharmaceutical product and many perishable products of all sorts. But fundamental to reliable vaccine distribution are reliable projections of demand and supply. With reliable projections of demand and supply then the other supply chain inputs can be appropriately secured and sequenced. Without substantial confidence relating to supply and demand, the vaccination network has sputtered and stalled in ways that tend to be amplified across the network. There has been a major effort made to provide states a three-week sure-thing window on forthcoming flows. That was supposed to begin on Valentines Day, but the Polar Vortex had other plans. It is, however, my impression that by late February “guaranteed minimums” were being regularly delivered and, in fact, our “wholesalers” at the state and local level have had challenges because in early March some deliveries exceeded those minimums.

What is Operation Warp Speed and how is it involved in vaccine distribution?

Operation Warp Speed was the name for a public-private effort to accelerate development, testing, and mass production of effective coronavirus vaccines. Many elements of the program are still operating, but Warp Speed is no longer referenced. The recent addition of the J&J single-jab vaccine is another output of the newest incarnation of this effort. I have been told that this effort has also been instrumental in bringing Merck’s vaccination production capacity into the mix to increase flows of the J&J product.

Beyond high-velocity vaccine development, testing, and mass production, OWS also developed a national distribution capacity and capability that has been used to distribute the Moderna product to the states and track all vaccine distribution.

I could, perhaps should, leave your question there, but I predict distribution will be the focus of a great deal of after-action analysis. From where I have sat, from what I have been able to see, it seems to me that the McKesson-plus-Many-Others capability that was put together was successful moving product from filling/finishing to the states. Pfizer did a good job of this too. We should not underestimate the value of this achievement. But after product handoffs to what I have called the wholesale level, Vaccine Utilization Rates have varied dramatically. Should federal, state, and local players — not just OWS — have done more? How could what I call the wholesale level have been better prepared to play a more demand-oriented role in distribution?

For your audience of supply chain professionals, I will share this observation — to which I hope the after-actions will give attention: Contemporary demand-oriented, data-driven, just-in-time supply chains work hard to squeeze out uncertainty, but every new product introduction, every holiday season, every hurricane season generates profound uncertainties to effectively manage. Uncertainty is, in some ways, the reason supply chain professionals exist. You plan and execute to minimize uncertainty. You demonstrate your capacity to respond to uncertainty under duress. You compete with each other on how well you can both minimize and exploit uncertainty. I don’t perceive that this self-definition, this professional discipline, this embrace of uncertainty, this career-experience with uncertainty has characterized the first ten weeks of the vaccine rollout.

How has the distribution strategy evolved since late 2020?

What I am calling the wholesale level — states, localities, public health agencies, hospital systems — have become much more proficient at last-mile supply chain operations and last-inch procedures. More access points are being set up: many more temporary vaccination venues and an increasing number of retail pharmacies are now delivering vaccinations to consumers. The supply chain is not yet demand-driven, but as supplies increase and points of access become more convenient it is much more demand-friendly, like Sears on some sunny day in June, 1971.

How do you think the arrival of new COVID-19 variants will affect current distribution plans?

The increasing prevalence of more contagious variants — and in some cases, potentially more lethal variants — lends even greater urgency to distributing as much vaccine volume as possible and pushing Vaccine Utilization Rates as high as possible. In early March, US data are mostly moving in the right direction. Confirmed coronavirus cases, hospitalizations, and deaths are all down from early January peaks. Most measures of US population mobility — human circulation — continue to be down about 25 percent. Vaccination rates are increasing. But what we have also seen in other places, especially in Brazil, is that the variants can seriously — and very suddenly — disrupt progress. The virus is evolving to outrun our constraints. During the last week in February and first week in March improving US data stalled. Is this a blip, a plateau, or the start of a variant-fueled resurgence? We don’t know. So, given the risk, our best bet is to keep building and using transmission roadblocks — vaccinate faster, reduce population circulation, avoid crowded interior spaces, continue face coverings, and so on — to keep cases and hospitalizations as low as possible until roughly seventy to eighty percent of the population is vaccinated.

On a more recent subject, how has the polar vortex impacted supply chains in the US? Has there been any major outlying impact on the distribution of vaccines?

Many, many supply chain impacts. For example, major disruptions of fresh produce and fuel refining; amazing fluctuations in the natural gas market, and significant shifts in the freight market for several days across several lanes. Vaccine distribution was considerably reduced on February 16, 17, and 18 and then bounced back much higher the next week to make up for what had been lost. This is not a system well-suited for volatility. So yes, there were enormous gyrations in local vaccination flows caused by the Polar Vortex.

So far, we’ve been focusing on vaccine distribution in the US, is there anything you can add about distribution in other parts of the world? i.e. do the strategies differ, how so, etc.

Among the most populous players the United States is well ahead on the vaccination front. As we speak in early March, the United States is administering about 1.9 million shots per day. That’s more than twice the number of vaccinations per day in the European Union, more than three-times the number of vaccinations per day in China, and almost 4 times the number of vaccinations per day so far in India. Israel has done a fabulous job of vaccinating its much smaller population (less than 10 million people). I do not want to claim any special insight on Israel’s distribution strategy. But it is well-known that one of the reasons Pfizer was motivated to maximize flow to Israel was an agreement with the Government of Israel to get fine-grained population health data back on those vaccinated. This benefit is possible because Israel has one of the most sophisticated digitally-facilitated population-health systems on the planet. In other words, Israel has been able to blend demand-oriented, data-driven processes with vaccine distribution.

What do we take away from this for future vaccine distribution strategies?

I take away that demand matters most. Of course there must be supply. But whether supply is insufficient, perfectly aligned, or over-abundant, how that supply is effectively distributed depends on demand-oriented decisions. This is especially the case when what is distributed can mean the difference between life and death. But as supply chain professionals know, this is equally true for any high-volume, high-velocity product: hamburger meat on July 2 and 3 or that fuschia shirt that just sold out in Barcelona, Paris, and New York. The better we understand demand, the more effectively we are able to target whatever volume and velocity is available. The better you understand human need, the more likely you are able to fulfill that need.