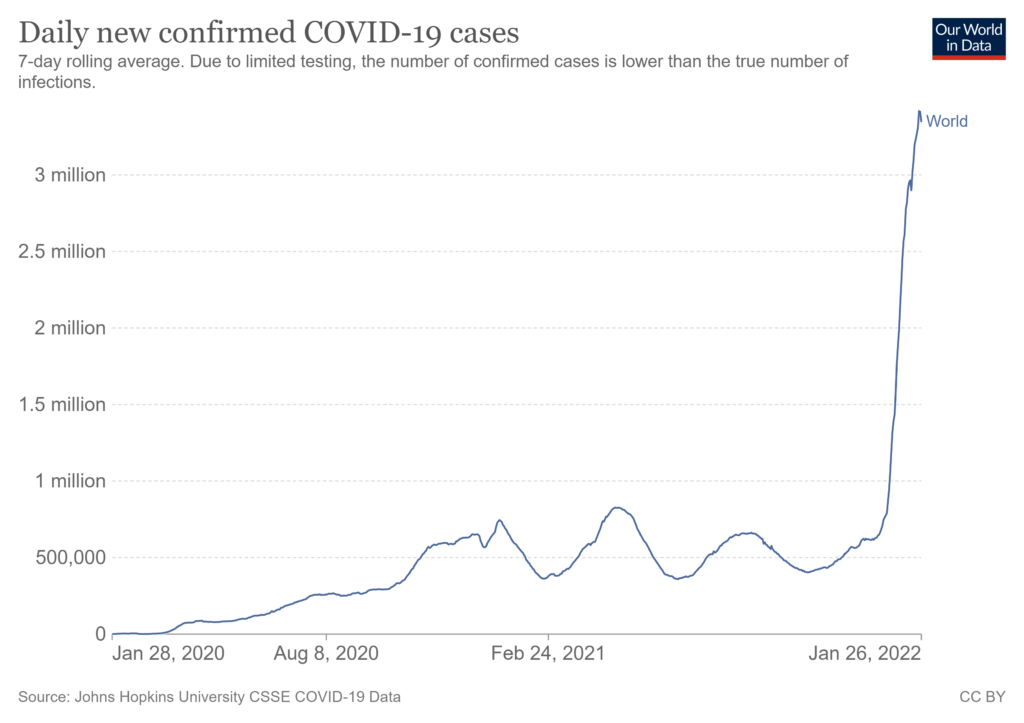

[Updates through February 17 are included below.] The US grocery supply chain continued to deliver most of what was wanted to most consumers in most places through the worst of omicron. There was significant employee absenteeism. There was increased friction in several flows. Some shelves were empty. Velocity was highly variable depending on day and place, but overall volumes were close to 90 percent of typical.

I may never see data that will confidently confirm or deny, but based on a small amount of quantitative data (mostly IRI and Federal Reserve) and what folks with eyes and ears on food flows tell me, I now perceive that grocery supply was probably most mismatched with demand between about January 12 and 19. There was (is) considerable regional/local variation. Less populated, less wealthy places farther away from grocery distribution centers generally had more stock-outs.

Demand was higher than January 2020. Depending on product category, demand was six (produce) to thirteen (bakery) percent higher.

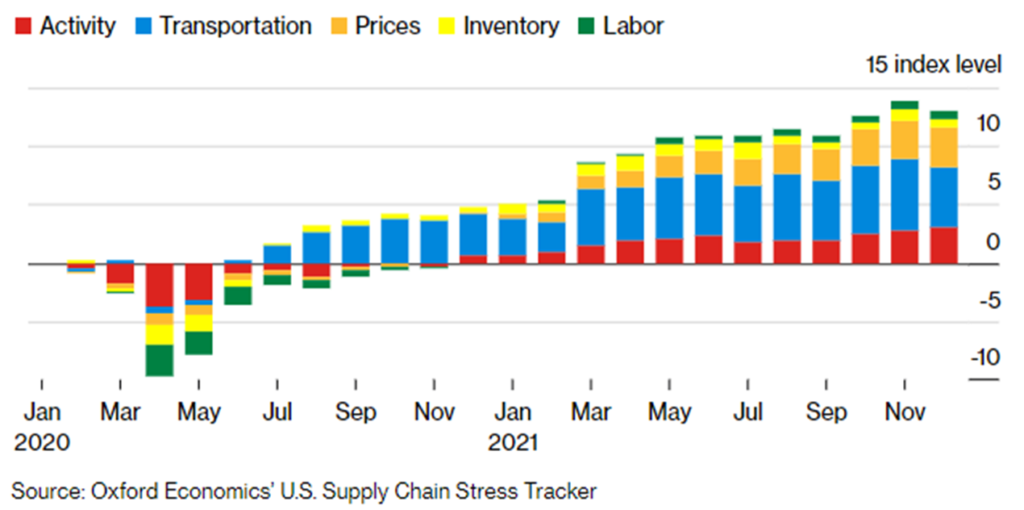

There were (and are) sourcing and production problems. Food processors saw a significant increase in worker absenteeism. Trucking, already substantially over-subscribed, had its share of sick drivers. There were also increased delays in loading and delivering groceries because of lack of personnel on both ends of this flow.

It is my strong impression that there has been more product available than the ability to move product. This friction exists across the whole network, but has been especially difficult between distribution centers and retail outlets. Distance and square footage of moving stock is a (mostly) fixed constraint on push. But in mid-January cycle times for operating vans were extended as it took much more time to load and unload. Then add six to thirteen percent increased pull. Faster pull + slower push = more empty slots on shelves. [This bottlenecking of midstream to downstream is a recurring characteristic of network friction well beyond groceries-in-a-pandemic.]

If you have been reading this space since early December, you know I was concerned about the potential for the grocery network in some major trading area(s) suddenly shutting down (here and here). This did not happen.

Flows persisted because consumer-pull did not experience a sustained sharp-surge (e.g., more than twenty percent for eight consecutive days or more), retailers were early implementing effective demand-management methods, and the US grocery sector is a robust, resilient system that is predisposed to persist. Over the last month, I perceive that this predisposition included thousands of workers continuing on the job when they were probably covid positive and certainly when they had been exposed. Given omicron’s contagious reach (more), I find it hard to imagine most food processing or distribution center or retail workers having not been exposed. Given constraints on testing, the virus usually comes and goes without confirmation.

In December I contributed to a process to facilitate flows as safely as possible given the risk of omicron. Some positive steps were taken. In my judgment these efforts had almost no substantive effect. Timing, communication, and implementation were too ponderous compared to the speed of omicron.

What mostly kept food flowing in January has been the independent actions of millions who decided — mostly — to buy what they needed and not much more and to show up to work despite the risks. We are fortunate that omicron’s morbidity is much less than some prior variants and that substantial proportions of the population have been effectively vaccinated. We are fortunate that high volume, high velocity networks tend to be so stubborn.

+++

What happened and did not happen with food flows in January will continue to be ambiguous. I probably will continue to blog on this topic. I will also try to aggregate relevant data outputs below. I hope for some new data even later today.

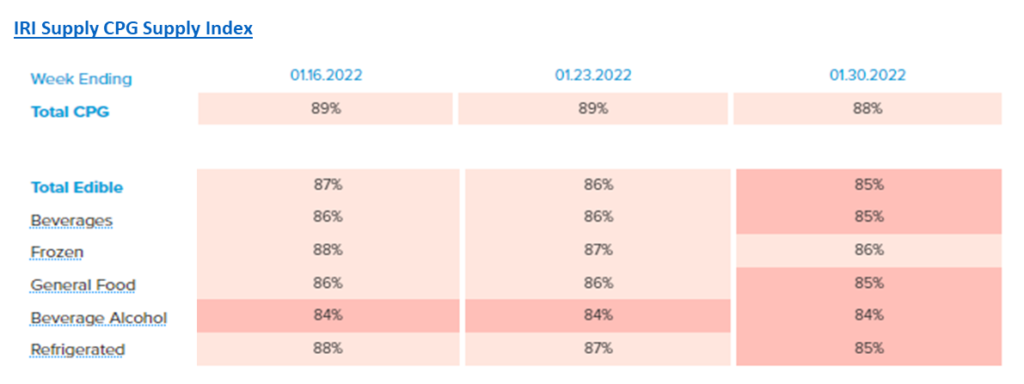

January 31 mid-afternoon update: Today IRI has released updates for its CPG Supply Index for the last two consecutive weeks (ending on January 23 and January 30). This morning I speculated that the worst grocery flows were probably experienced between January 12 and 19. IRI’s assessment finds that that in-stock levels of edible categories declined one percent each for each of the last two weeks. I could be one week off or store inventory could lag flow (but by a week seems long to me). In either case the second-half of January had slower grocery flows than anyone wanted.

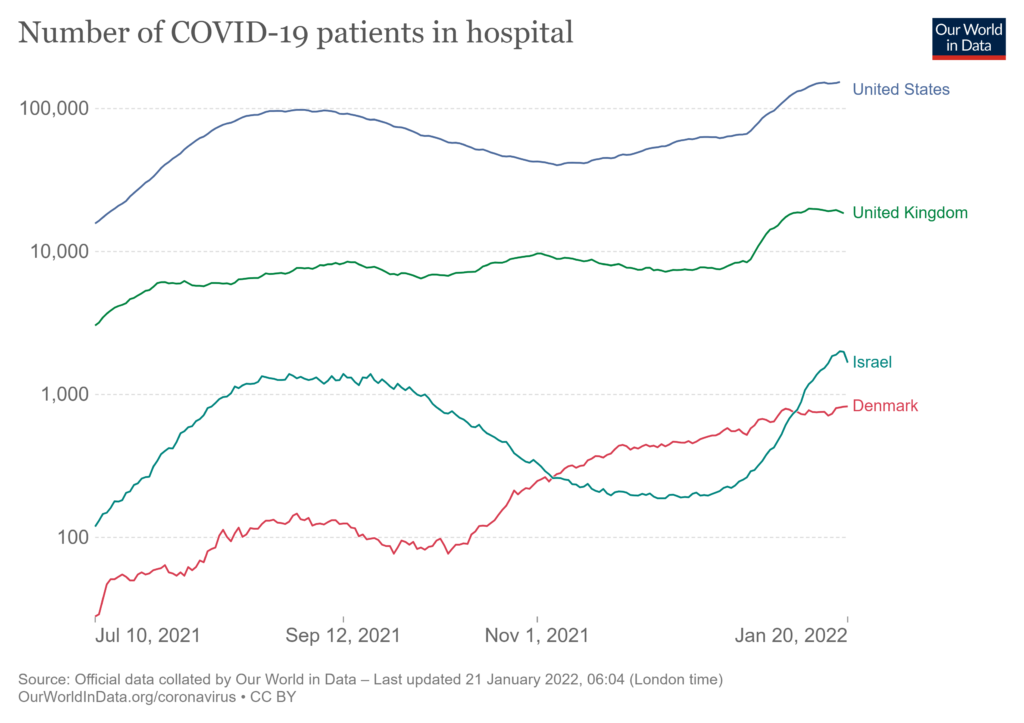

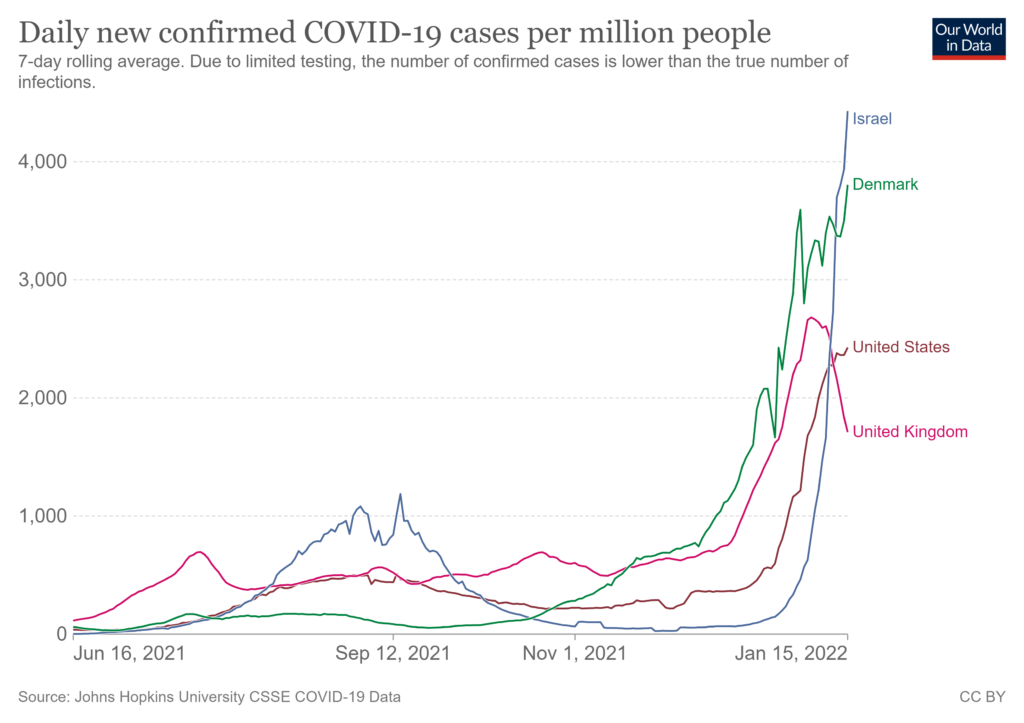

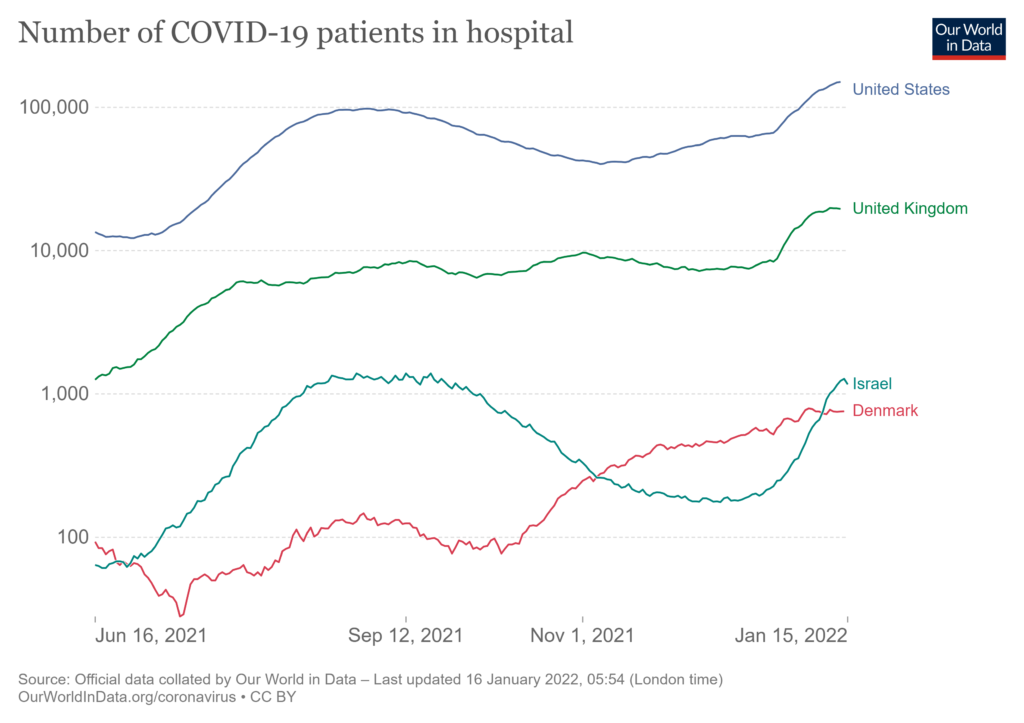

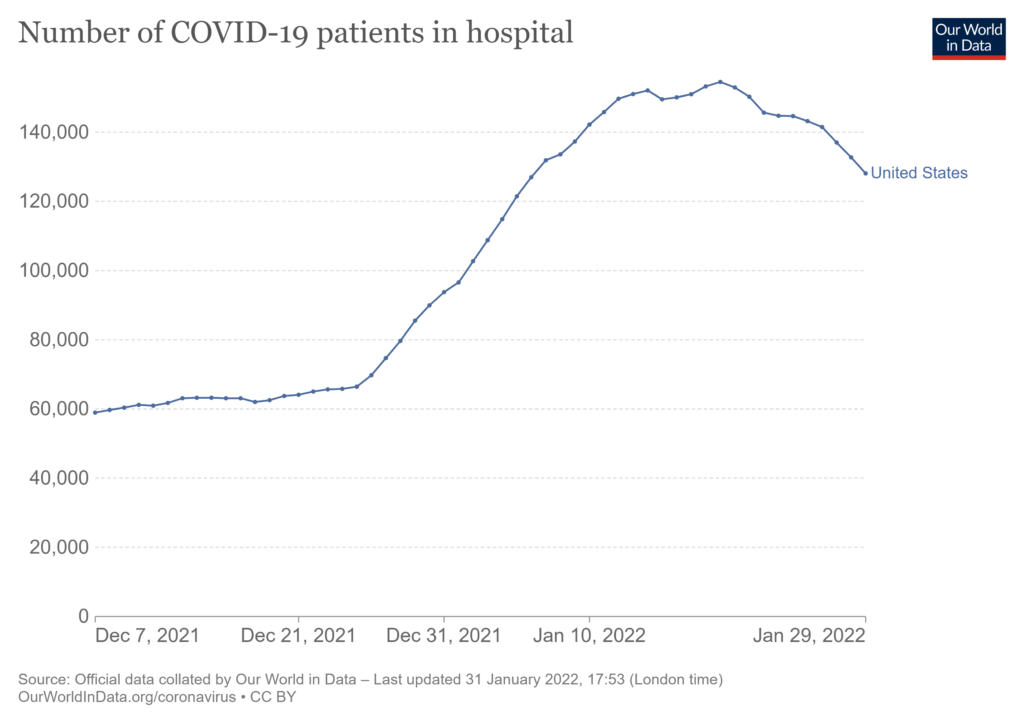

Below is the actual number of US hospital admissions for which covid has been confirmed. The omicron surge basically started with Christmas and peaked on January 19. Did workplace absenteeism coincide with or lag this indicator of morbidity?

The December job reports (released on February 4) include clues to how flows kept going in January. Job-leaving in January increased to 952,000 and 1.8 million Americans reported they were “prevented from looking for work due to the pandemic.” Given the omicron surge, these were not surprising outcomes. But despite this serious friction, new January hires were a surprisingly strong 467,000. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics:

Employment in transportation and warehousing increased by 54,000 in January and is 542,000 higher than in February 2020. In January, job gains occurred in couriers and messengers (+21,000), warehousing and storage (+13,000), truck transportation (+8,000), and air transportation (+7,000). All four of these component industries have surpassed their February 2020 employment levels, with particularly strong growth in warehousing and storage (+410,000) and couriers and messengers (+236,000).

Absenteeism was up (how much is still up in the air), but businesses continuing hiring. I wonder if worries over absenteeism and other workforce constraints may have actually encouraged more new hiring?

February 7 update: The Sunday Washington Post has a good piece (posted online on Saturday) with retrospective color-commentary on the workforce context during the December-January omicron surge: Despite Omicron Surge, Businesses Desperate to Find and Keep Workers.

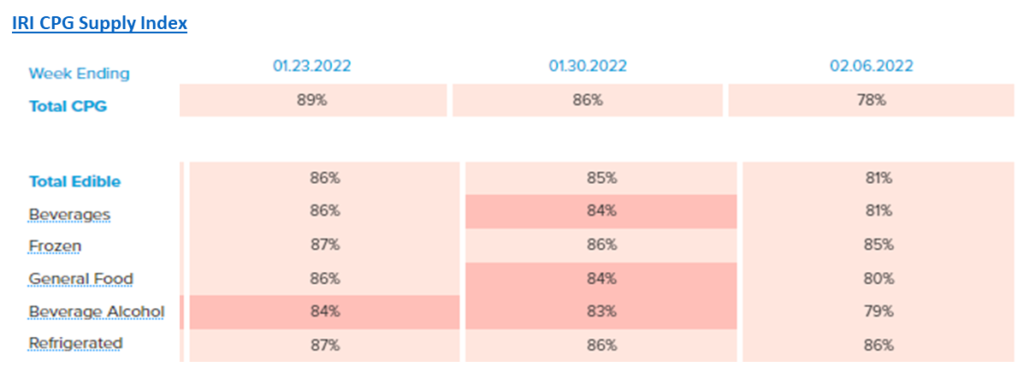

February 9 update: The IRI CPG Supply Index for the week ending on February 6 shows stock-outs continuing and, in some cases, worsening. The four percent drop in General Food was especially sharp. Stock-outs in non-edible may suggest decisions at the distribution level to use available assets to deliver food instead of beauty products (pure speculation).

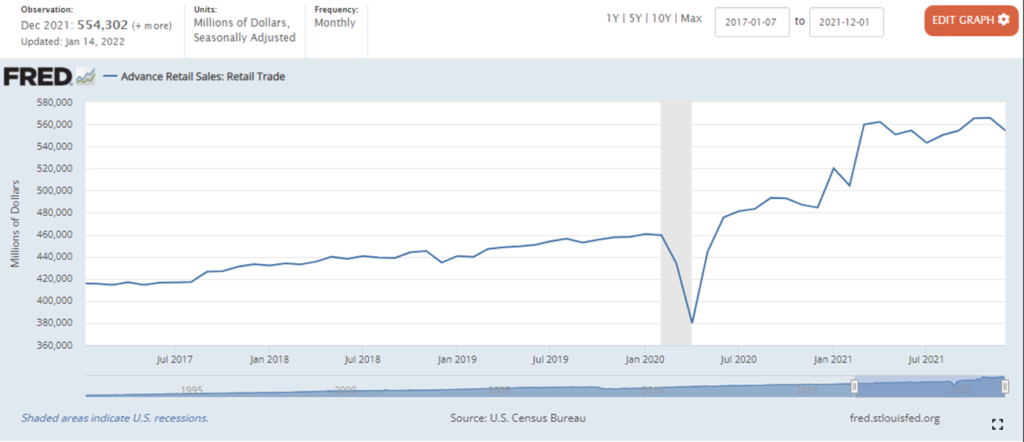

Demand has continued strong since Christmas. Year-Over-Year pull for General Food has been up 7 to 8 percent since mid-January (and 2021 demand was about 7 or 8 percent higher than 2020 demand). But while demand sets the stage, during the first week in February a huge snow and ice storm impacted populations (and roads) from Texas to New England, spurring pre-storm stockpiling and slowing replenishment. Already low inventories were partially the result of omicron worker absenteeism, but the most recent plunge in available produce has a more traditional, seasonal cause.

February 15 Update: The Bureau of Labor Statistics is confirming/clarifying omicron’s impact on January flow capacity. I also comment on this in another post.

February 17 Update: The Census Bureau’s Pulse Survey (experimental) finds that during the period January 26 to February 7 a total of 7,772,708 employed Americans were not working because they were experiencing covid-related symptoms or caring with someone with covid symptoms. Another 5,049,124 were caring for children not in school or daycare. Another 3,016,462 were not working because they were concerned they would be infected or spread the coronavirus. For the period December 29 to January 10 the numbers for these three categories (in the same order) were: 8,753,923, 5,327,065, and 3,216,749. A Pulse Survey was not conducted during the two weeks January 11-January 25. I’m guessing absenteeism peaked during the intervening data-darkness. It is also worth recognizing that while increased absenteeism was constraining supply capacity, retail demand hit a new high (more). In the grocery sector, food sales did decline from December (Christmas) totals, but January 2022 sales were $70,010 million compared to November’s $68,948 million and the year-over-year comparison to January 2021 was 7.7 percent higher compared to $64,656 million. Yikes. I am just amazed at the power and persistence of grocery demand this late in the pandemic.