Here is my — our? — supply chain resilience problem to be solved:

In a large-scale catastrophic context, how can continued flows of water, food, medical goods, and pharmaceuticals be best assured? How can sourcing, processing, and production of sufficient volumes be achieved? Given available capacity, how can the freight velocity of inputs and outputs be maximized? Answers to these three questions always raise related questions of energy and fuel supplies. There is considerable consensus regarding these key issues.

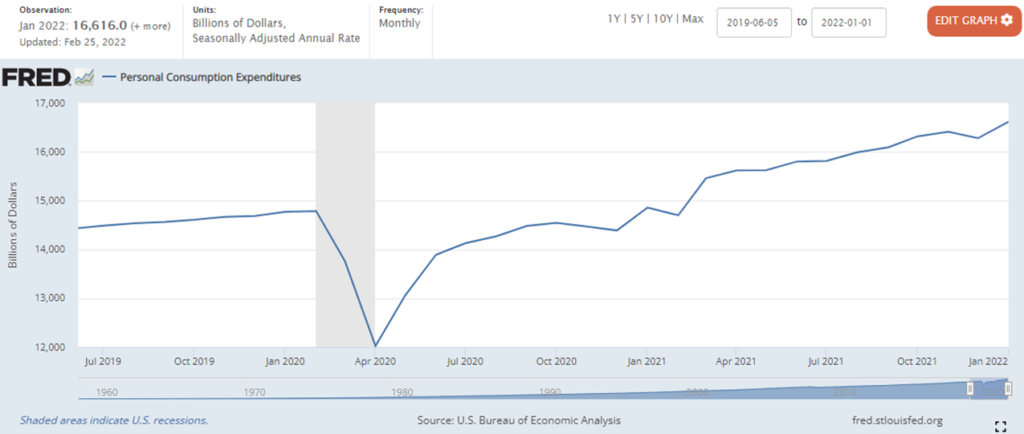

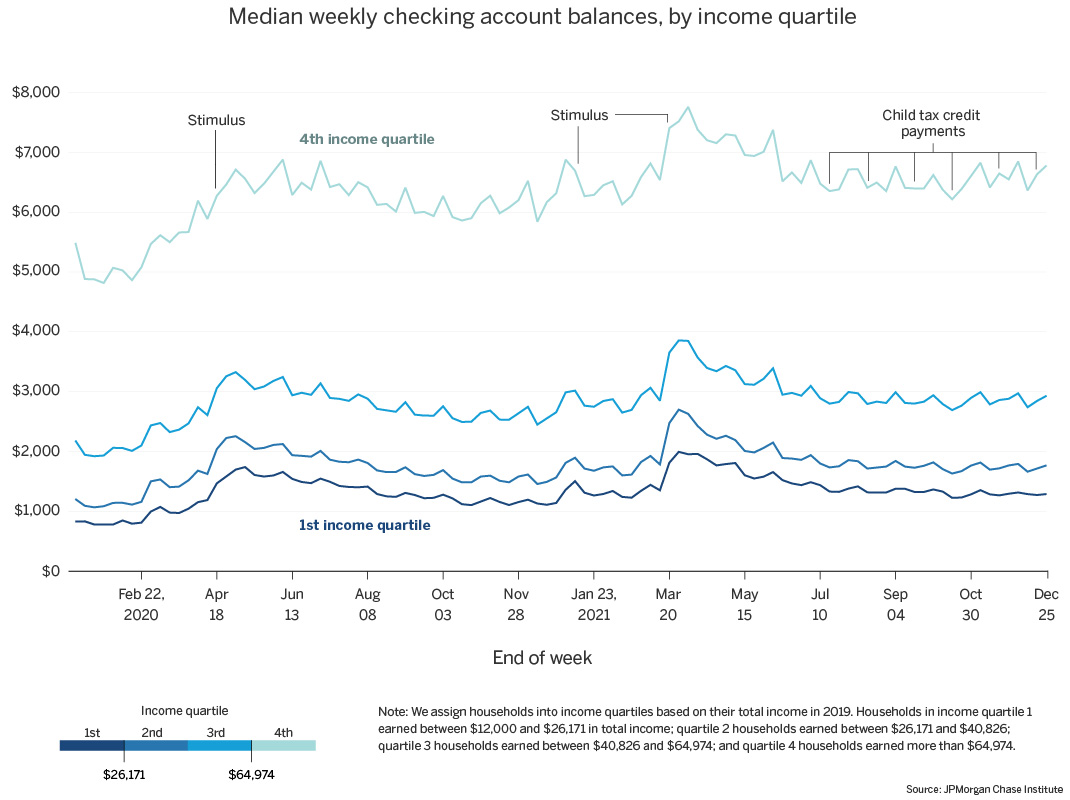

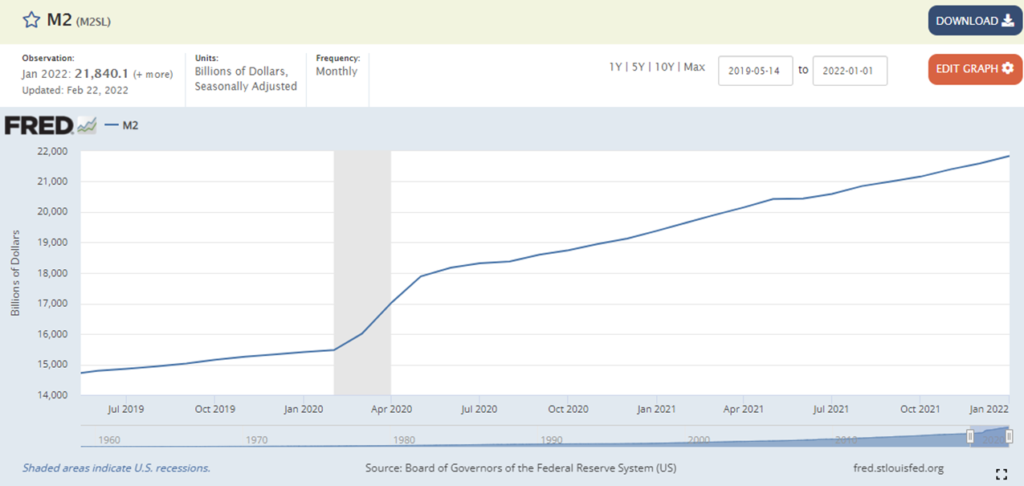

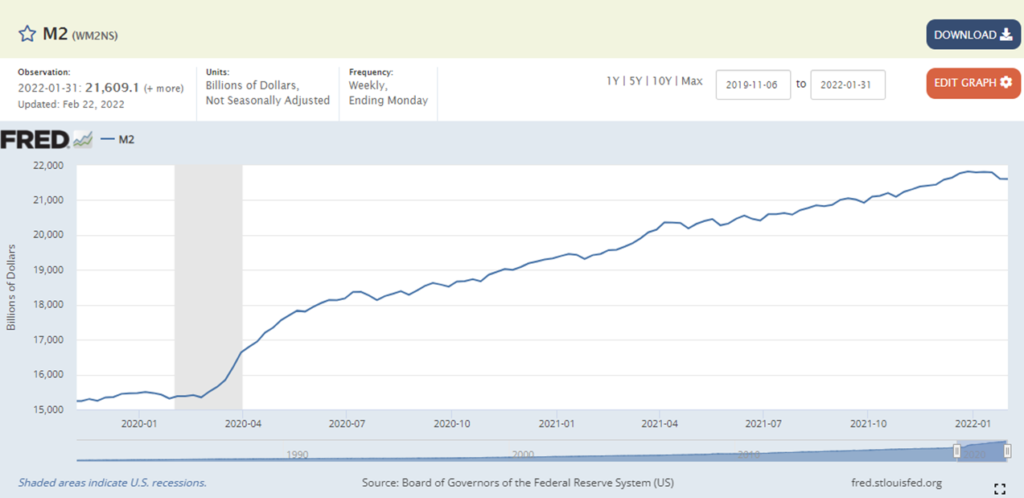

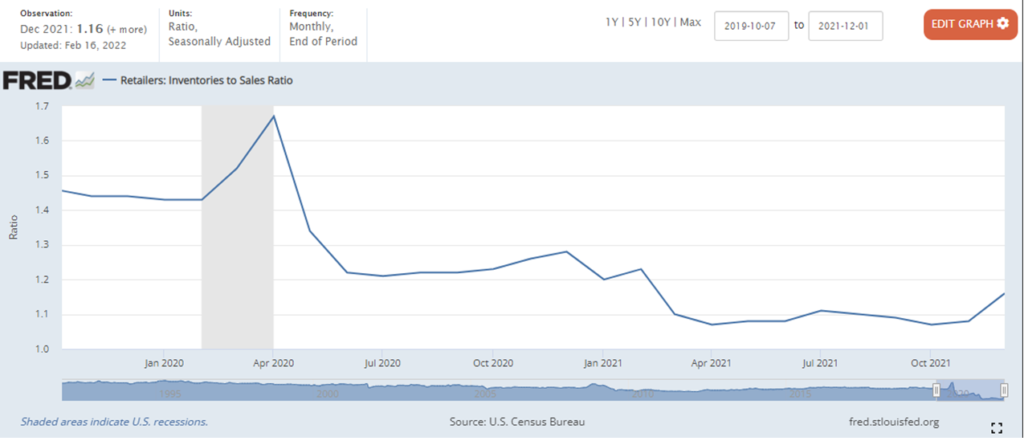

I am persuaded (others are not fully persuaded) that fundamental to finding successful answers for the foregoing is preserving or quickly reestablishing a population’s ability to express demand. In large, advanced economies the velocity of supply reflects accurate measurement of demand. For thirty-plus years this has increasingly been done by tracking and sharing transaction details via telecomputing networks. Typically this depends on the electric grid and the cell network; both of which are lost or seriously degraded by anything worth calling a catastrophe. Without well-targeted demand, it is not possible to effectively deliver available volumes. With well-targeted demand, supply volumes and velocities have demonstrated rather amazing adaptability.

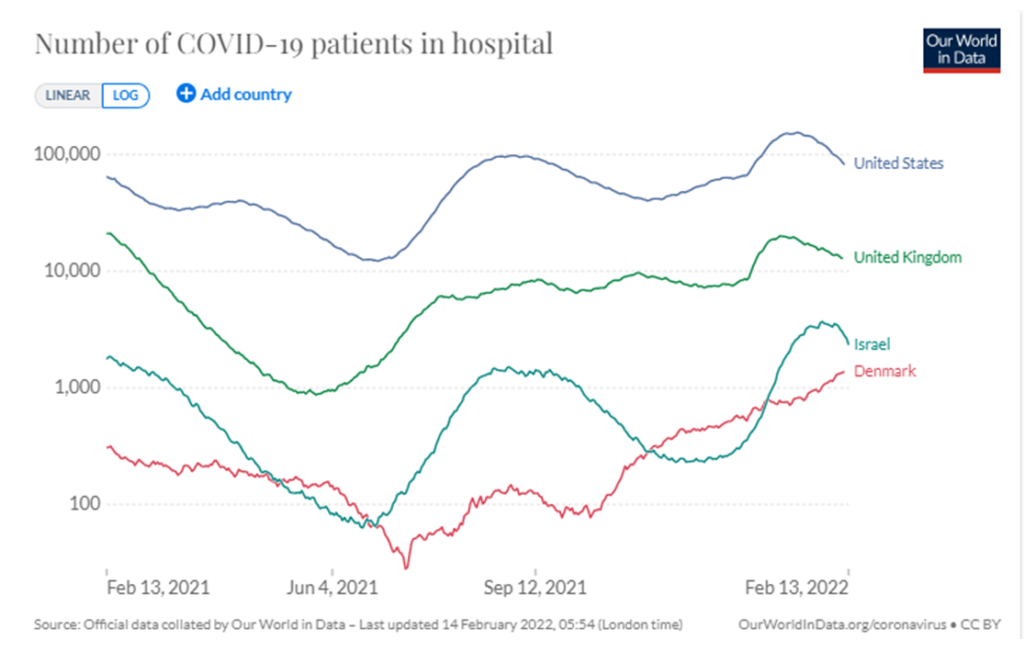

In most catastrophes there is a surviving strategic capacity to produce sufficient volumes of food, medical goods, and pharmaceuticals. This reflects the geographic distribution typical of these production capacities. Water can be more problematic. Very high volumes need to be locally distributed for human sanitation and fire suppression. A sudden onset loss of water systems serving a large population (for example, caused by a seismic event or long-term grid failure or contamination) can quickly present deadly threats related to human hydration.

But if water can continue to be locally accessed, other life-critical products can almost always be supplied with enough freight movement — usually meaning trucks and fuel — going to the right places at the right time. Even water system complications can be mitigated if trucks can quickly deliver repair equipment, back-up pumps, and fuel for emergency operations. The interdependencies can get very complicated. But even in catastrophes, sufficient flows can usually be restored if:

Demand can be accurately sized and located,

Demand can be effectively accessed by trucks,

Refueling is available for trucks and emergency electrical generation (e.g., water pumps, cell towers, digital transaction systems…).

It may still be tough and treacherous, but if these priorities are effectively achieved, time and opportunity expands.

On Thursday the White House released six reports — well, at least five reports — directly relevant to the problems set out above. USDA has generated a report on production and distribution of agricultural products. The Department of Health and Human Services looks at the public health supply chain. Department of Commerce and Department of Homeland Security focus on information and communications technology (by which demand is expressed and measured). The Department of Transportation reports out on freight and logistics. The Department of Energy offers analysis that has important implications for fuels.

These five reports, plus one more from the Department of Defense, are the result of a presidential directive released last February. Here are the opening lines of that Executive Order:

The United States needs resilient, diverse, and secure supply chains to ensure our economic prosperity and national security. Pandemics and other biological threats, cyber-attacks, climate shocks and extreme weather events, terrorist attacks, geopolitical and economic competition, and other conditions can reduce critical manufacturing capacity and the availability and integrity of critical goods, products, and services.

This national need is broader than my problem, but my problem is relevant to — and depends upon — how this need is achieved. I agree that Supply Chain Resilience is best approached from a strategic, capabilities-based angle, rather than a tactical, threat-based position. Over the next two weeks I intend to take on each sector-specific report and try to discern a coherent cross-sector strategy.

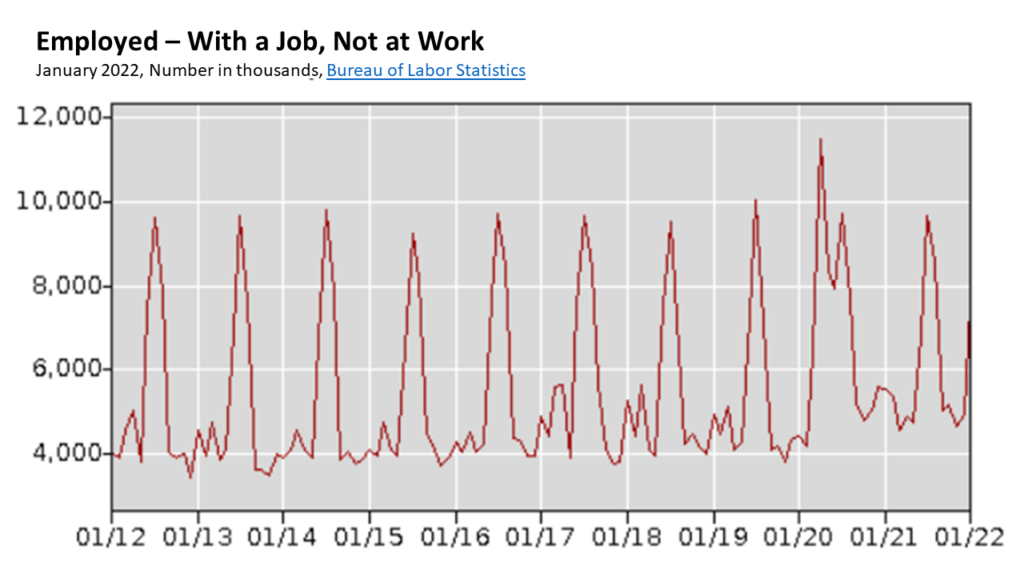

During the twelve months these reports were being developed the United States and the world arguably experienced the most far-reaching supply chain challenges ever, certainly in the thirty-some-year history of contemporary supply chains. These reports reflect influential expert interpretations of this shared experience. Over time these written reports could contribute to our collective interpretation as much as our direct experiences… for better or worse, even better and worse.

It is also possible that emerging experience has already superseded these efforts. Supply chains have morphed considerably since the Executive Order — are morphing dramatically this morning (more and more) — and there is plenty of potential for new realities still unfolding.

In any case, as I complete each related consideration I will also link each below.

Agricultural Production and Distribution (March 1, 2022)

Public Health Supply Chain (March 2, 2022)

Freight Flows (March 7, 2022)

Fuel Flows (March 10, 2022)

Information Flows (March 14, 2022)

Demand and Supply Dialectics (March 18, 2022) Seeking synthesis