In the week prior to Halloween (before Amazon with Apple dramatically highlighted supply chain constraints), Tom Keene on Bloomberg Surveillance offered the best concise summary of supply chain realities that I have heard. He said, “It’s microeconomics and there’s ambiguity and there’s give-and-take and, frankly, there is an unknown and we are learning as we go in a natural disaster.” (Please see below, start listening at about the 59:52 mark.)

Over the last several months I have written many more words. But TK seemed to spontaneously summarize what really matters.

Still, many want more detail than Mr. Keene provided, but more clearly and concisely than is typical of my method. So, as some of you have requested, here’s one more try.

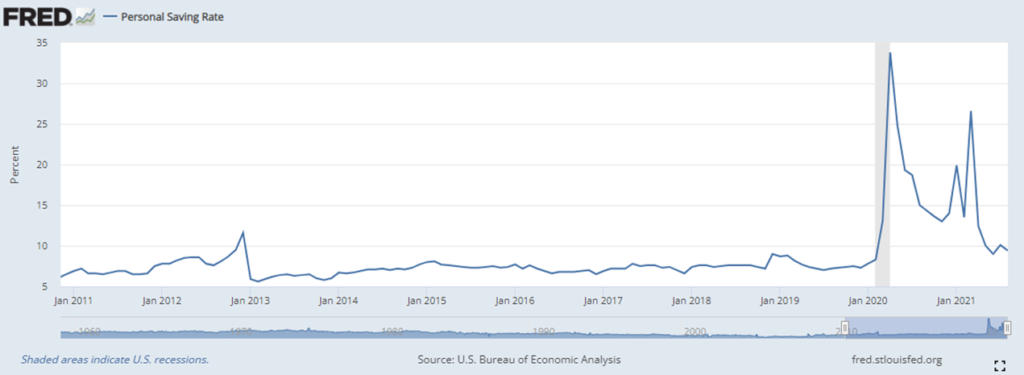

Early in the pandemic US consumer demand fell hard and fast by about one-fifth. Then between May 2020 and about March 2021 overall consumption recovered. Since this March overall demand has increased by another half-trillion dollars per month. This demand is usually being fulfilled.

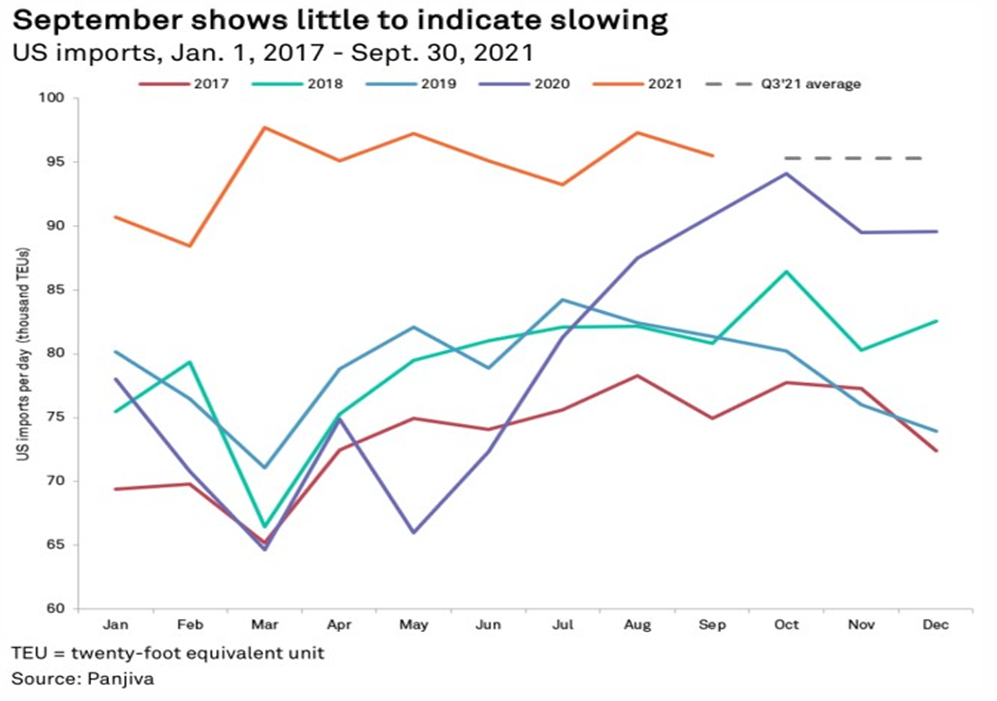

But where consumers once purchased lots of services — like travel, entertainment, and eating out — over the last 18 months consumers have focused on a lot more stuff, even twice as much stuff (more).

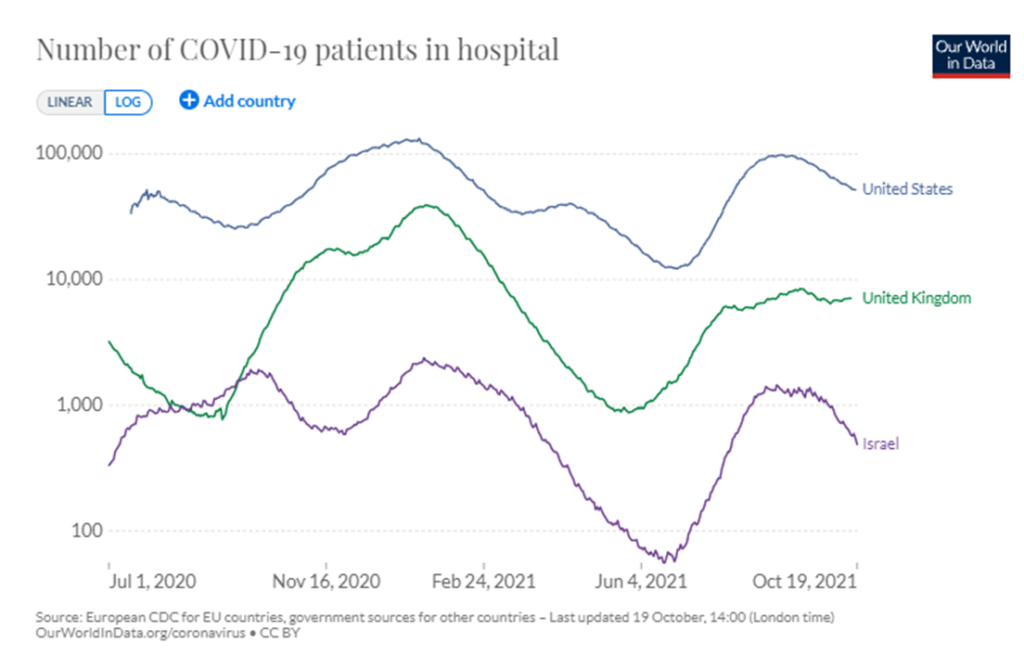

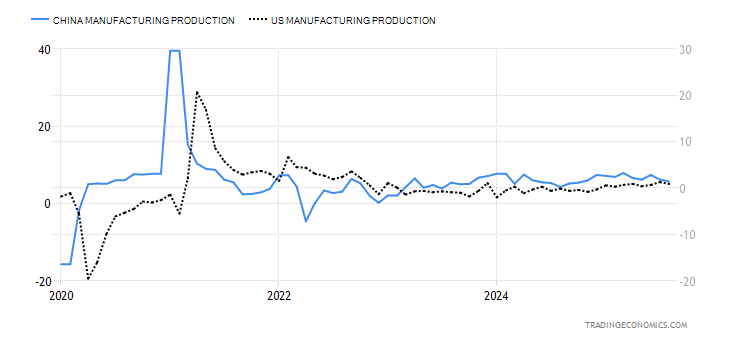

Producing and delivering this much extra stuff this quickly would have complicated and congested flows in the best of all possible worlds. But trying to supply this surge and shift during a pandemic has been extra tough. Constraints on time and space intended to mitigate disease transmission have reduced production and distribution capacity. Disease penetration has been even more disruptive. Shifting upstream capacities created proliferating and unpredicted downstream gyrations

Persisting supply chain friction has amplified human fatigue and frustration (and even fear) that has further constrained system capacity (e.g., workforce retirements, resignations, reimagining careers, non-participation, and more). Friday Amazon’s CFO explained, “For the foreseeable future, our capacity constraint is actually labor, which is new and not welcome.”

Supply chain constraints are promiscuous and breed additional constraints. Efforts to mitigate this proliferation of constraints (e.g. port congestion) have been complicated by issues of distance between supply and demand and over-concentration of channels (e.g. ocean shipping and port capacity).

These aggregated frictions (and complex feedback signals) are now constraining some fundamental flows, from food to fancy high-tech phones. Which products or categories are most at risk at this point seems to me more and more a betting proposition than anything else. Chop and wind in every channel are sufficient to threaten just about everything on offer. It is a mess. As previously outlined, I do not perceive the mess as an existential threat (except to some smaller retailers). But it is certainly an equal opportunity mess with the potential to seriously complicate economic outcomes for an extended period.

As consumers have less cash to spend and the proportion spent on services increases, overall pull is very slowly beginning to even out (more). Over-time (probably by March-April 2022, barring a more insidious virus or similar) this will result in noticeably improved equilibrium of demand and supply. If and when volatility returns to something closer to pre-pandemic patterns is another Vegas bet.

This increasingly frustrating experience reveals the dangers associated with over-concentration of supply networks, especially when amplified by distance, and the current lack of effective structures for the exploration and exploitation of enlightened self-interest in managing the global ecosystem of demand and supply.