[Post-landfall updates continue below.]

Hurricane Melissa is forecast to make landfall on Jamaica sometime early on Tuesday, October 28 (more). It will probably be a slow-moving Category 4 or 5 storm bringing catastrophic rains and 140 mile-per-hour plus winds.

High winds and coastal storm surge will wreak havoc. The impact of flooding on transportation and water infrastructure is of particular concern. Thirty and more inches could inundate much of Jamaica on October 27 and 28.

Almost 3 million people live on Jamaica. The island is roughly 145 miles long and 50 miles wide (or about 4400 square miles, 11,000 square kilometers).

In 2024 Hurricane Beryl passed near Jamaica as a Category 4 storm seriously disrupting the electrical grid’s distribution network. But power was restored for over 90 percent of customers within one week. Hurricane Gilbert (1988) disrupted both distribution and transmission networks leaving many without power for months. (More and more.)

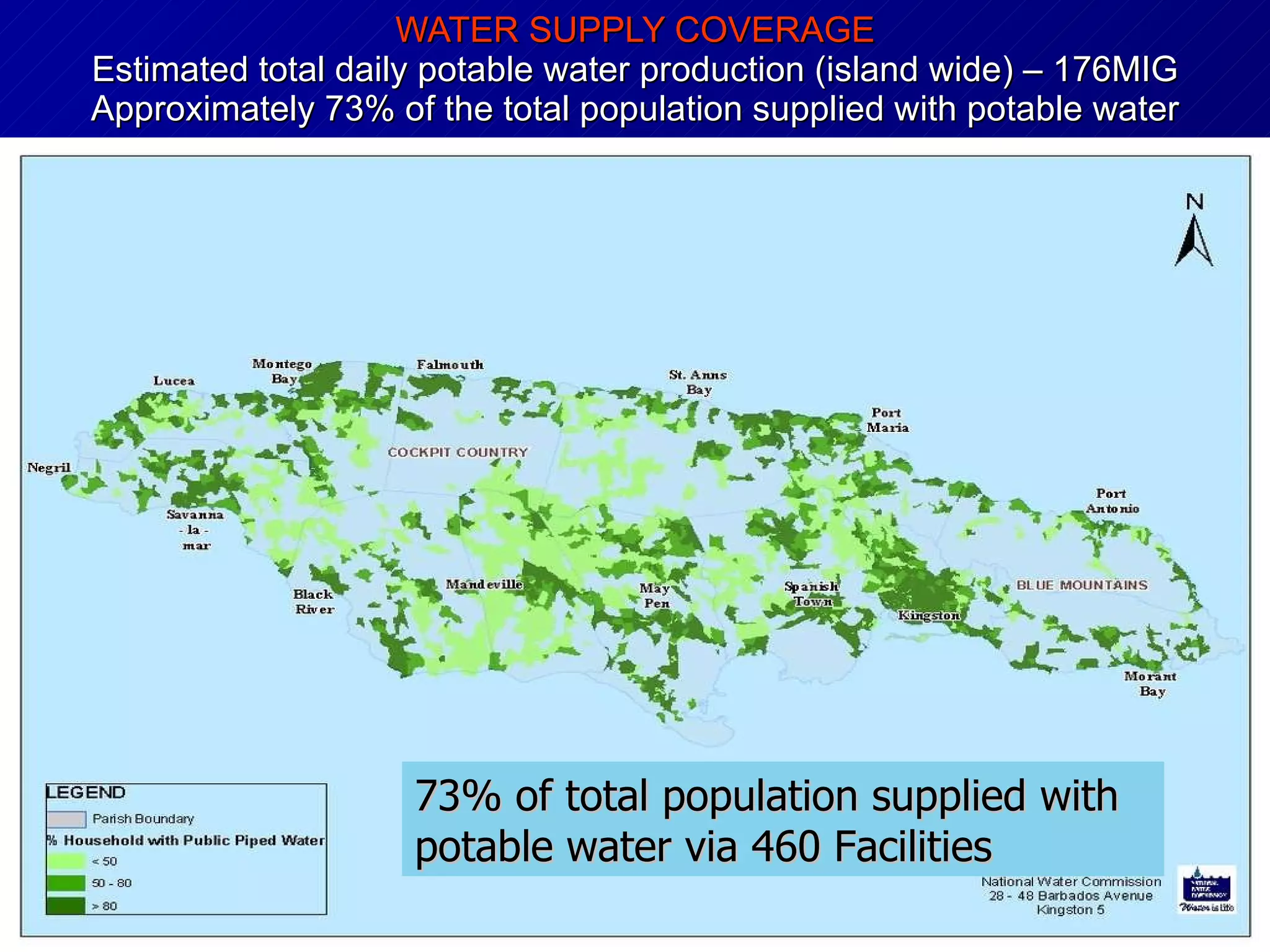

Jamaica’s National Water Commission supplies potable water for almost three-quarters of the population (see map below). Over 80 percent of Jamaica’s water is pumped from groundwater. Pumps require grid power or emergency back-up power. Electrical generators require fuel.

Petrojam Ltd. operates a petroleum refinery near Kingston. But Jamaica imports much more refined fuel than it produces. In recent years, over sixty percent of refined fuels consumed in Jamaica have been imported, mostly from the United States. Refined fuels are used to generate a high proportion of Jamaica’s grid power. In case of a long-term grid outage, fuel demand is likely to increase to support water pumping, cell tower operations, warehouses, trucking, and emergency generation needs. Supply and demand could experience exacerbated disequilibrium because fuel to generate electricity is often not the same as fuel to satisfy other energy consumption needs. Fuel distribution/delivery is mostly by truck. This distribution capacity is not sufficient to gap-fill infrastructure, commercial, and residential demand during a long-term grid outage in combination with transportation impediments. (Here and here and here.)

About eighty percent of Jamaica’s food is imported, mostly from the United States. Roughly 60 percent of food flows usually support the tourist sector in Jamaica (here). Major grocery retailers include Progressive Grocers, Hi-lo Food Stores, and PriceSmart. A market leading food importer/wholesaler is Everything Fresh. Continued or disrupted flow by these high proportion providers should offer meaningful indicators of overall network fitness in the aftermath of Melissa. As is the case for most islands, the food supply chain serving Jamaica is not especially Just-In-Time. Substantial warehouse stocks are usually maintained — especially for hurricane season.

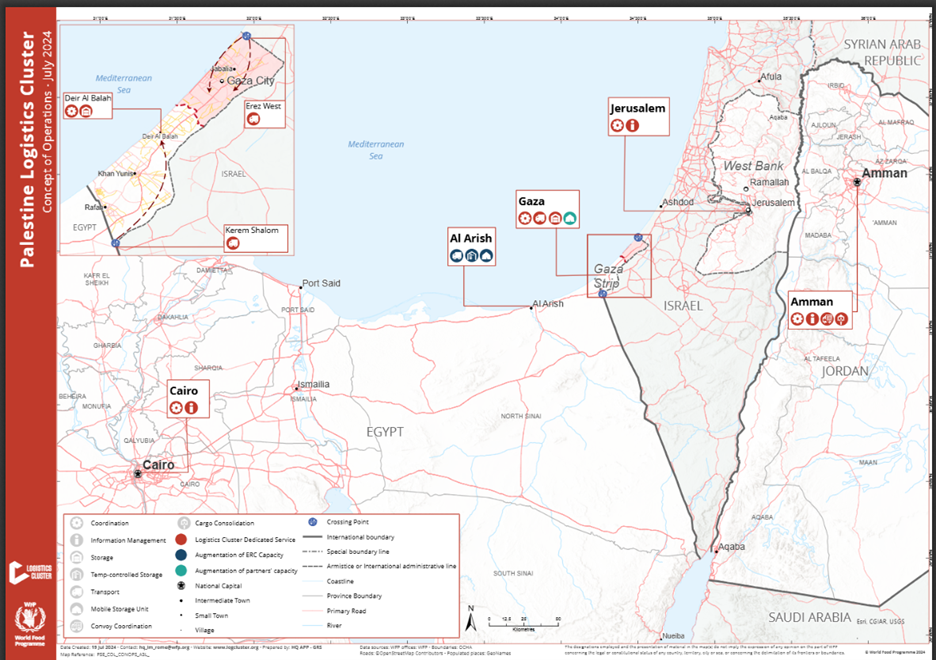

Melissa seems likely to cause time-extended grid outages. The longer the grid is down the more important recovery of water systems, fuel delivery, and food availability. Strategic capacity for fuel and food is concentrated at the Port of Kingston (more and more). If port operations can quickly resume, upstream flows will resume. Maritime movement — or current lack of movement — can be monitored here. The nearest NOAA buoy is over 200 miles southeast of Kingston. Wave and wind forecasts and history for Port of Kingston are available here. The Crowley Maritime schedule for Jamaica (more) will also help confirm and clarify the general velocity of inbound post-hurricane flows.

Pumping capacity for system replenishment is the most important flow-point (or choke-point) for providing potable water. This capacity is currently distributed over more than 150 pumping sites. As a result of this decentralization, catastrophic loss of capacity should be mitigated. But if the grid is gone, then fuel flows inbound and outbound of Kingston become even more important. Monitoring — and facilitating — fuel flows through the neck of the network’s hourglass at Kingston could become the key means for expediting flows of fuel and food and water to survivors.

[NOTE: As of Monday morning, October 27, web-based resources hosted in Jamaica are loading more slowly or not available.]

+++

UPDATE October 28, 0400 Eastern Time: Slow moving, CAT5 Melissa remains southwest of Jamaica. Landfall is now forecast for late morning or this afternoon proximate to the 78th Meridian (see map below). The current forecast for the Port of Kingston suggests the worst conditions will emerge mid-afternoon with wind gusts above 50 mph, wave heights of 12-16 feet, and rain accumulation exceeding one inch per hour for much of this afternoon.

UPDATE, October 29, 0400 Eastern: Melissa just made landfall on eastern Cuba (here). The situation in Jamaica will remain uncertain until sunrise allows for closer and wider observations. But early indicators suggest key elements of network capacity for receiving and moving water, food, and fuel have survived. According to the Kingston Gleaner newspaper:

Hurricane Melissa, according to the US National Hurricane Center, made landfall near New Hope, Westmoreland, with wind speeds of up to 185 mph. As the disaster pummeled those areas, rendering far lighter winds and rainfall in the capital city, Kingstonians tuned in to weather broadcasts and social media reports relaying reports of massive flooding, heavy winds, and the overall trauma of what the Meteorological Service of Jamaica (Met Service) warned was the island’s worst disaster. “We have been spared, but at the same time St Elizabeth and Westmoreland haven’t been spared,” said Burgess [a Kingston-based civil engineer], expressing dismay for Jamaicans affected in those primary hit parishes, and also those impacted in the eastern islands.

The maritime channel south of Jamaica is busy again. At least four tankers can be observed heading for Kingston harbor. Webcams at the port area show calm conditions and lights (here and here). It will be a tough and extended recovery for thousands in Jamaica. But it appears that response and recovery will be supported by significant continuity of network capacity.

Force on Target is fundamental to resilience probabilities. Melissa was (and remains) a monstrous force. But the hurricane’s targets in Western Jamaica encompassed the island’s least concentrated population (see map above) and almost no concentrations of supply chain capacity. If the same force had made landfall 75 miles east, consequences would have been massively multiplied.

UPDATE: October 30, 0600 Eastern: The Port of Kingston does not seem to have opened yet. Details of channel safety or channel clearing are not available to me. But the number of vessels now anchored off the port suggest that maritime operators expect to be able to offload soon. Yesterday, Wednesday, local media reported that the port expected to reopen today. I count at least six tankers and three cargo vessels standing by. Midday yesterday about three-quarters of Jamaica’s grid customers continued in the dark, but water system disruptions were being characterized as “minimal” (here). Reliefweb is aggregating helpful multi-agency reports here: https://reliefweb.int/country/jam

1100 hours Eastern (October 30): I still don’t have “official” confirmation that the Port of Kingston has reopened, but the terminal is certainly conducting operations and I see a handful of vessels at the docks.

UPDATE: October 31, 0400 Eastern: The Port of Kingston is open and was fully operating yesterday. On Thursday twenty-one vessels arrived. This morning I count eight cargo ships at the docks (see AIS mapping image below), several more are at anchorage nearby, and eight new vessels are scheduled to dock today (October 31). Both cargo and tanker vessels are contributing flow.

Roughly seven out of ten grid customers continue without power (see before/after satellite views below). CAT5 impacts obviously tangled the distribution network island-wide. In the hurricane’s direct path over western Jamaica a complete re-build of the distribution network will be needed in many places. I have not yet seen a credible assessment of impacts on Jamaica’s transmission network. My guess is that yesterday’s efforts were focused on triage opportunities for restoring grid power to high priority facilities and assessing/planning how to prioritize next steps. Anywhere the transmission network has failed will receive high priority attention. While transmission networks are recovered there will be slow progress in reconnecting the distribution network.

The resilience of food and fuel supply chains are especially (obviously?) crucial in case of a long-term grid outage. If the port was not receiving and discharging food and fuel — “feeding” survivors, emergency generators, water systems, and transportation — the risk of thousands not surviving Melissa would be much higher than it is today with flow disrupted but persisting. (More and more.)

UPDATE, November 1, 0700 Eastern Time: I am not yet finding or hearing well-documented assessments related to Jamaica’s electrical grid. I am aware of various reports that claim up to seventy percent of the transmission network has been seriously damaged. This is plausible, but should not be accepted without much more validation. Pre-Melissa Jamaica’s grid consisted of about 750 miles of high voltage transmission lines and about 12,000 miles of distribution lines (12-24 kV). Seventy percent of the distribution network being down strikes me as consistent with other evidence. I suppose a high proportion of longer-distance transmission lines might transit east to west through the worst impacted north-south corridor. But I don’t want to accept such a dire estimate for the transmission network — and related recovery calendar — without much more corroboration.

UPDATE, November 2, 0500 Eastern Time: Credible reports — specifically from Jamaica Public Service — indicate that grid outages have now been reduced from more than three-quarters of customers to somewhat less than six in ten customers (here). Most of the restoration involves the distribution network on the eastern third of the island (including metro Kingston), but there are also reports of progress being made in harder hit central and western areas. According to The Gleaner newspaper: “JPS has also indicated that it is providing power to 92 National Water Commission (NWC) pumps, which is 37% of its critical facilities. These pumps are located in St Thomas, Kingston, St Andrew, St Catherine, and Clarendon.”

UPDATE, November 6, 1500 Eastern Time: According to Jamaica Public Service — the national grid operator — their grid damage assessment has now been completed. They report that as of this morning 93 percent of transmission lines and 96 percent of sub-stations are operational. Approximately 70 percent of the electricity distribution network is operational. Roughly half of customers are currently connected to grid power. I have asked but have not received an answer as to how 70 percent of the distribution network has been recovered, but only half of customers are reconnected. I have also not — yet — found web-based written confirmation of this information. Several firms have done initial estimates of insured losses. These estimates range between $1.5 billion to $4.5 billion. Rough estimates of total losses are more than 10X insured losses.

UPDATE, November 13, 1100 Eastern Time: According to the Jamaica Observer channeling reports from Jamaica Public Service, almost two-thirds of Jamaica’s grid customers have been reconnected (more). This slow but steady progress is consistent with a widely shredded distribution network, but substantially resilient transmission and generation networks… especially when a surge in restoration crews is geographically and financially constrained. On November 12 the government’s Office of Utilities Regulation launched a webpage providing an interactive map with electricity, water, and telecommunications restoration updates by parish.