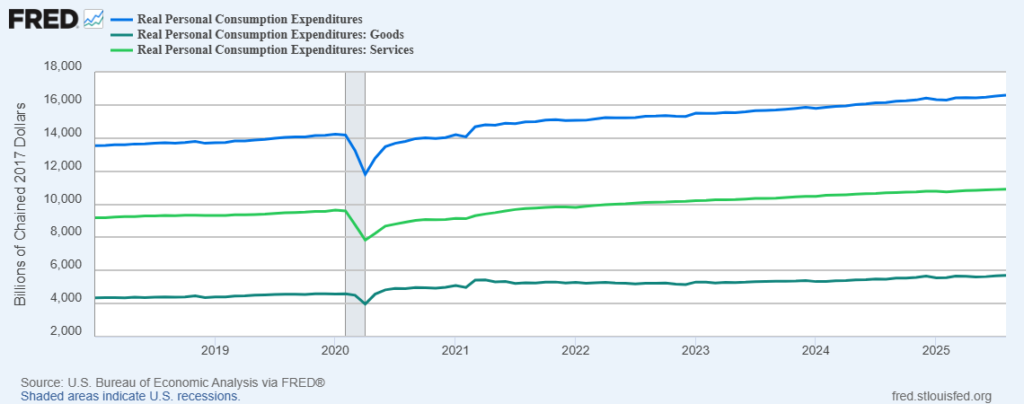

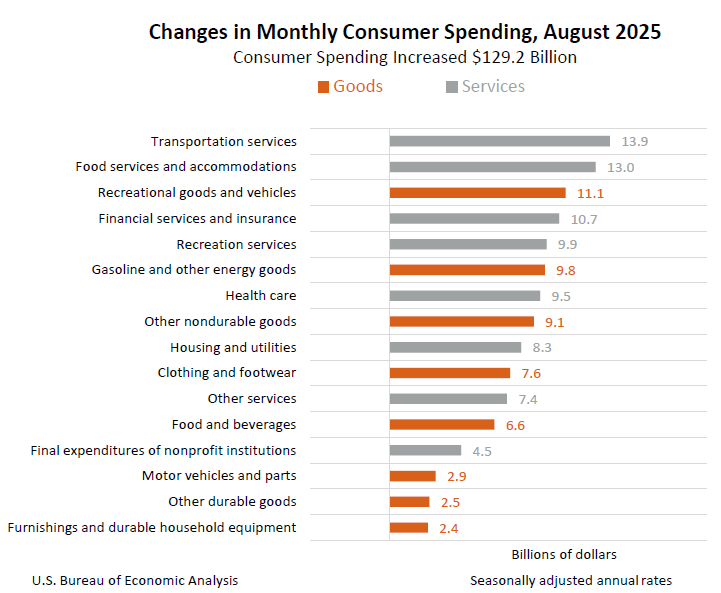

According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, during August US consumers earned and spent a bit more. “Disposable personal income (DPI)—personal income less personal current taxes—increased $86.1 billion (0.4 percent) and personal consumption expenditures (PCE) increased $129.2 billion (0.6 percent).” These are nominal, not-inflation-adjusted measures. The first chart below shows the real, inflation-adjusted, expenditure pattern.

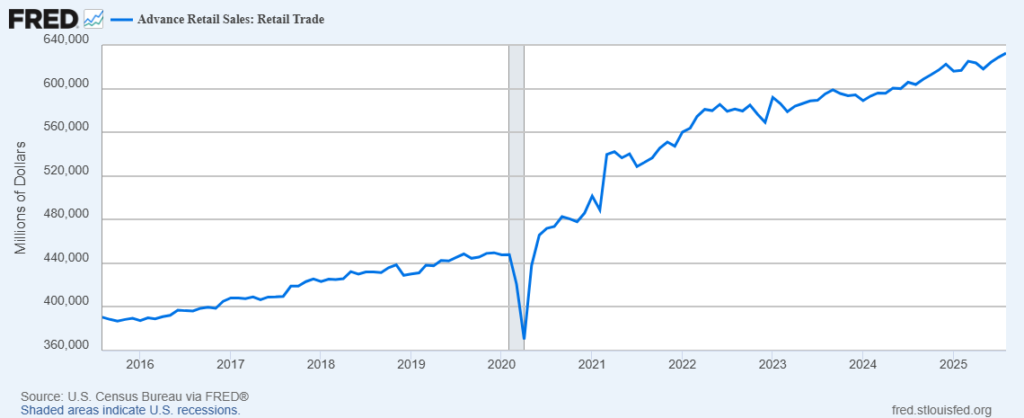

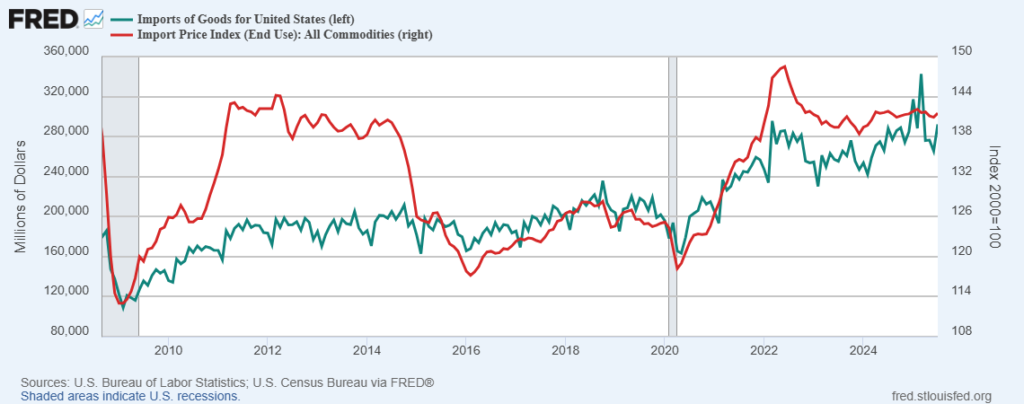

This volume and velocity of demand-pull can sustain strong supply-push, even in the context of significant flow volatility (e.g., here and here and here and here).

In its reporting on August Personal Consumption Expenditures, Bloomberg included, “Services were the driver behind the advance in PCE inflation while goods prices were tame. In particular, prices for recreational goods and vehicles, major appliances and household supplies all declined. Such discounts helped propel spending in those categories.”

The Washington Post explains, “The wealthiest Americans have been doing even better than previously thought — and are driving a consumer spending surge that has been fueling the U.S. economy as they splurge on travel, hotels and dining out, newly-revised economic data shows.” (More and more.)

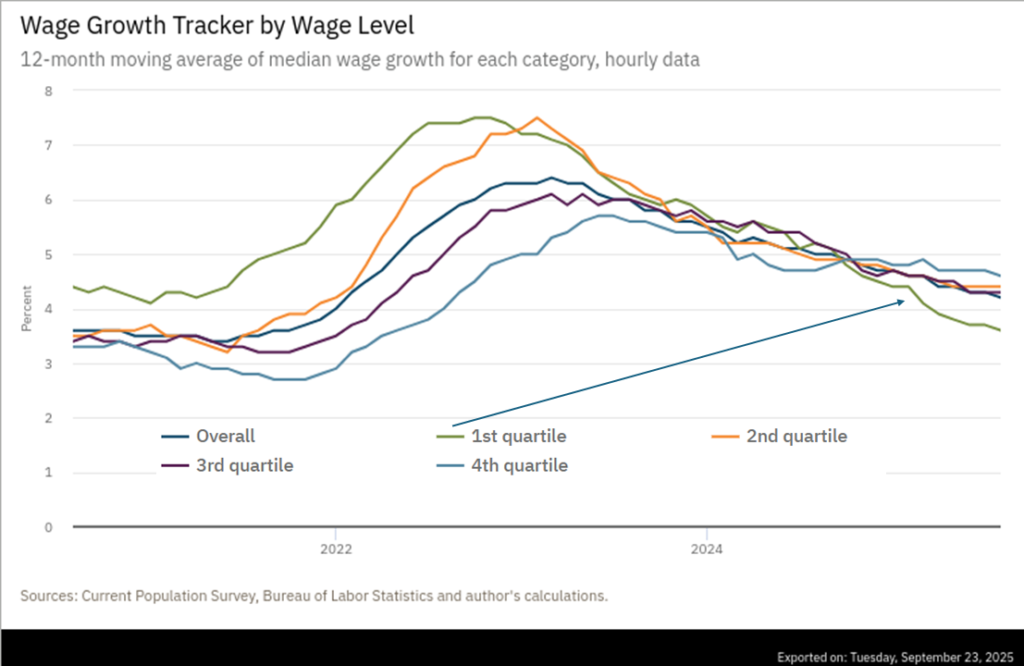

US consumer spending has been described as “exceptional“, “stubborn“, “surprising“, and “crazy“. But President of the Richmond Federal Reserve Bank, Tom Barkin, says, “… recent data show consumers resumed spending over the summer, especially those with higher incomes. And why wouldn’t they? Unemployment is still low, nominal wages are still increasing, and asset valuations are near all-time highs.”

There are — and have been — indicators of lower spending ahead (here and here). But, so far, actual consumer behavior has earned the adverbs used above. The soon-to-be-upon-us holiday season should be informative. Tariff related price increases seem to be trickling into retail prices. Credit card spending is down from last December (if still historically high). Since the pandemic, consumption by the upper one-fifth of US income earners has seldom shown much sustained restraint. If restraint surfaces the economic reaction — perhaps over-reaction — could be considerable.

+++

At about the same time I posted what’s above, Bloomberg published a very helpful overview of the global context for August PCE. As I wonder and worry about how long US consumers can continue their recent spending habits, the authors of the Bloomberg report see continued positive potential. “The US economy grew in the second quarter at the fastest pace in nearly two years as the government revised up its previous estimate of consumer spending. The third quarter is also looking solid, with recent reports illustrating resilient consumer spending and business outlays for equipment…” especially in comparison with other major economies.