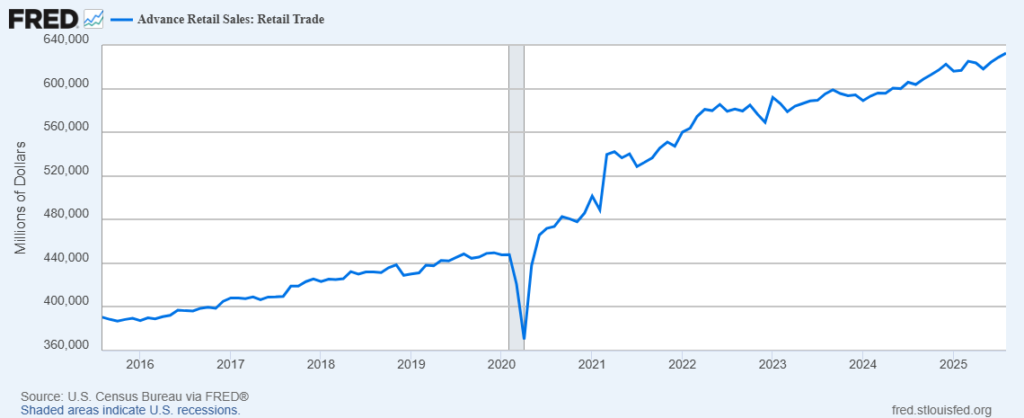

US retail sales increased in August, even more than expected. See chart below. Bloomberg initially characterized the outcomes with, “consumers are still spending even as tariffs boost the cost of some goods, sentiment remains subdued and the labor market shows signs of faltering. Though wage growth has cooled, many workers’ pay gains continue to outpace inflation, and others, particularly the wealthy, are benefiting from a stock market rally.” This sort of demand velocity should be sufficient to continue recent high volume flows.