Maritime food flows from Cyprus to Gaza were a good idea when first proposed in early November (more). This idea was even more promising last December when the EU endorsed and Israel signaled a tentative readiness to cooperate. If flows had actually begun in January our current context would be much more constructive.

Maybe the idea is on the edge of becoming more than an idea after last night’s push by President Biden (more and more ). The European Commission president is in Cyprus today to accelerate the diplomatic context and enable practical progress. Innovative private-public options are being floated.

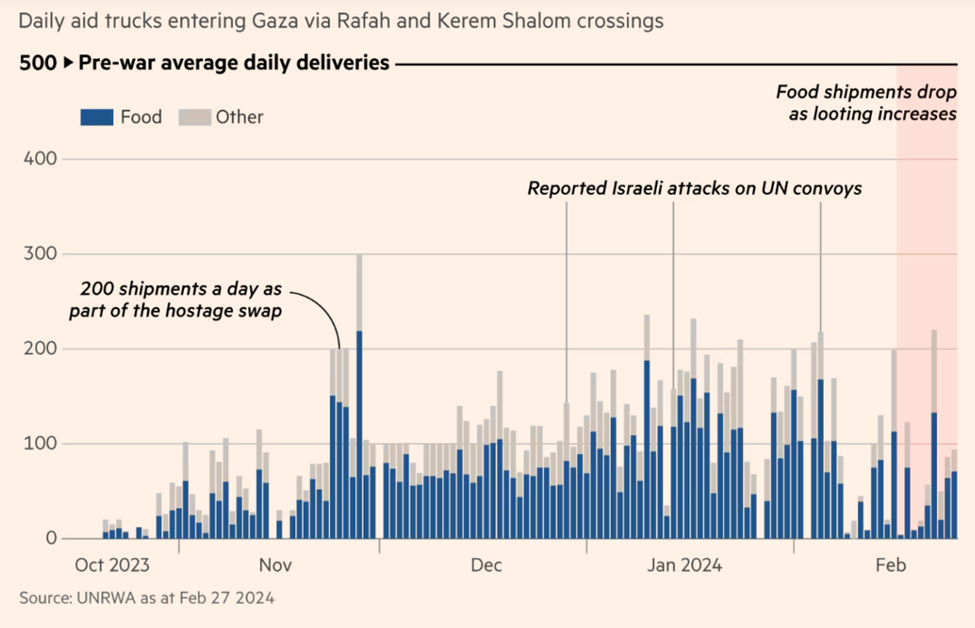

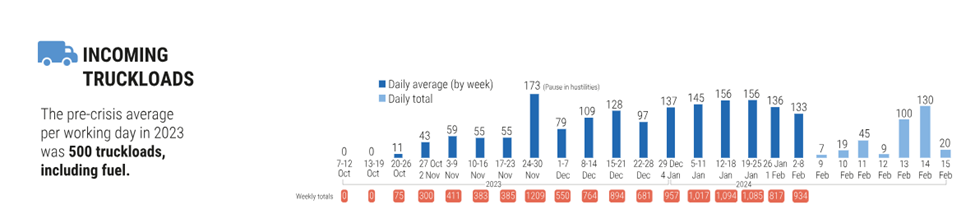

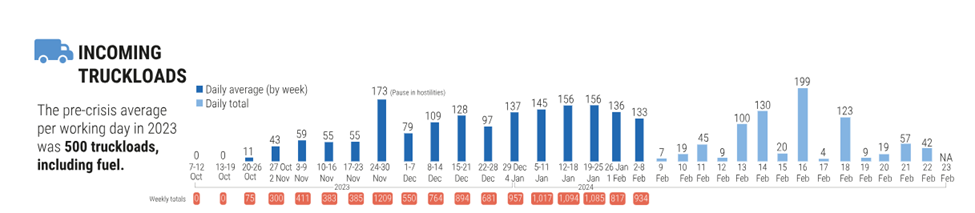

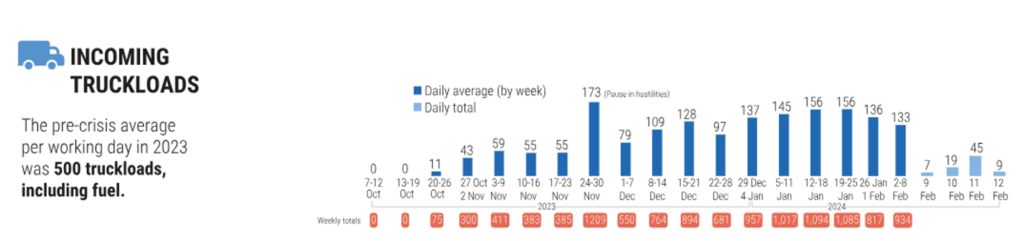

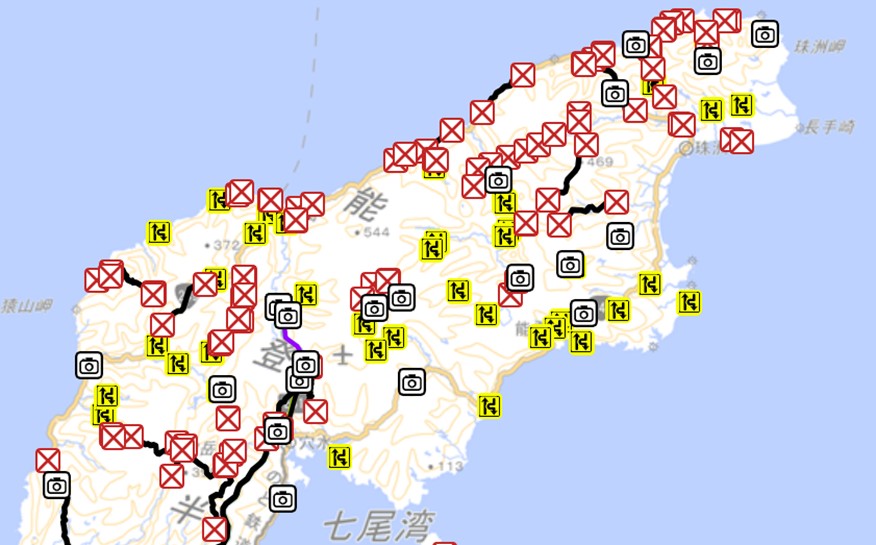

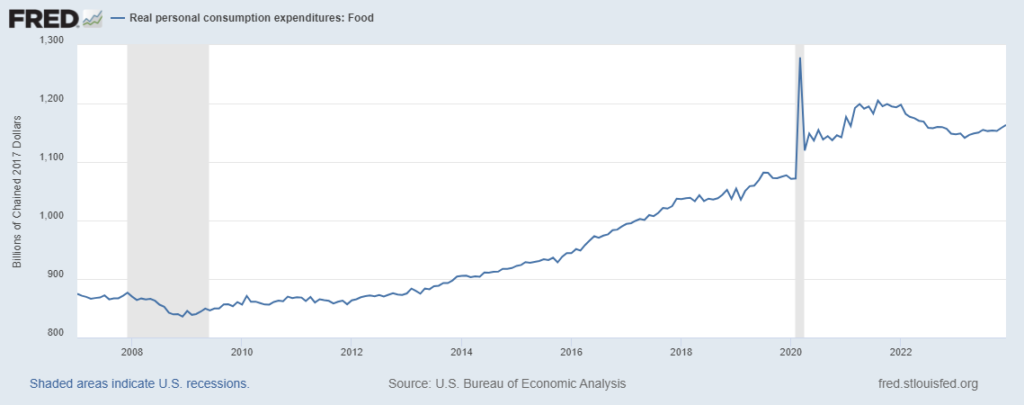

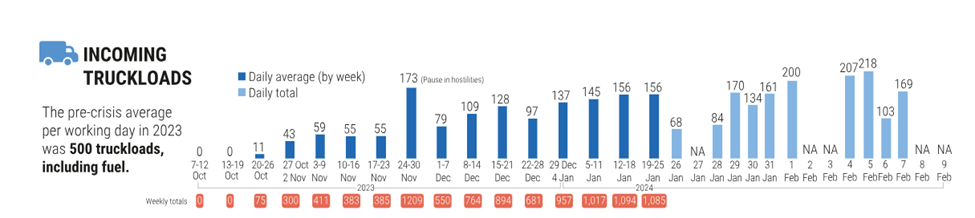

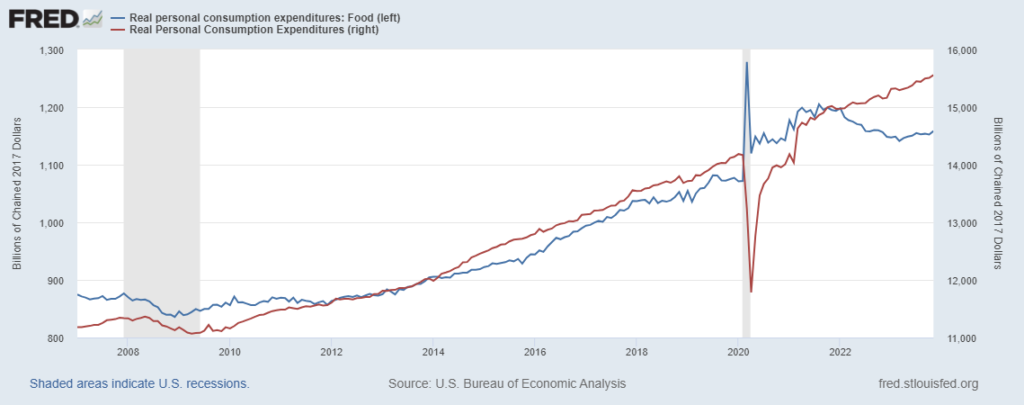

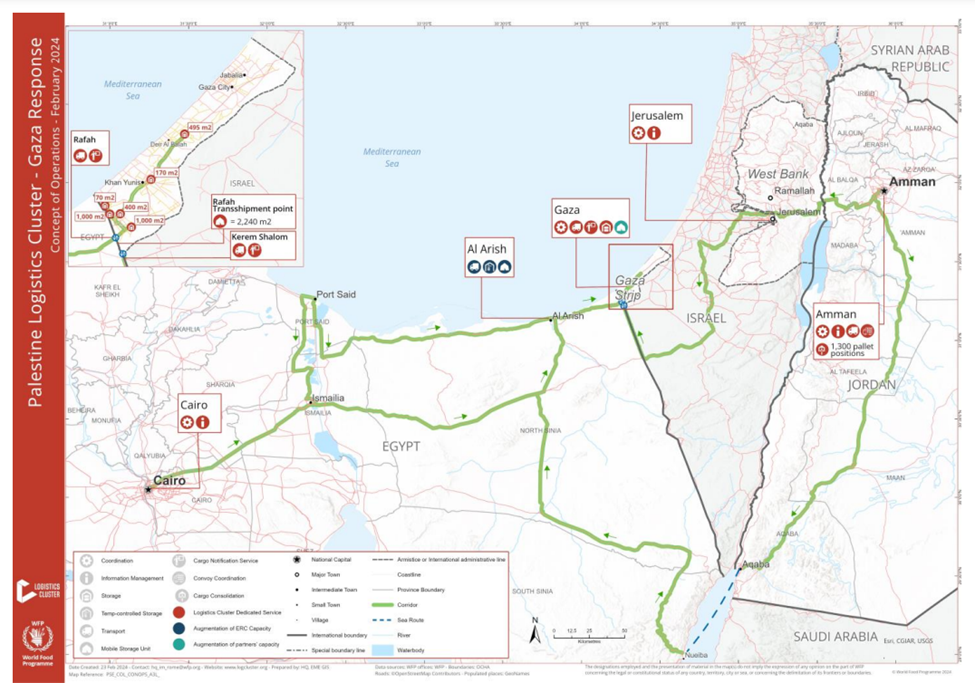

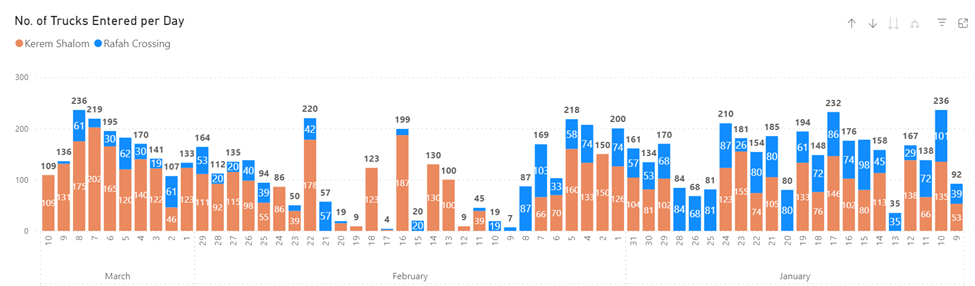

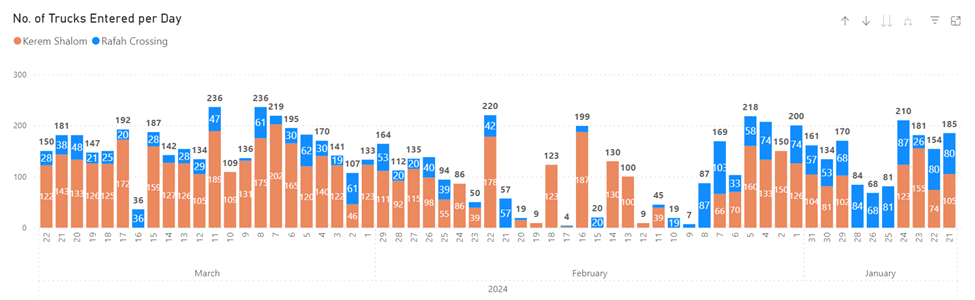

An even better idea is for preexisting overland freight flows to be regularly discharged into Gaza and effectively distributed to hungry people across Gaza. (See current capacity map below.) But it is now well past time to recognize that this better idea is susceptible to insidious delays… and an already urgent situation is becoming more desperate each day. Please see recent measures of sparse inbound Gaza freight flows in the chart below (more). By now we ought not allow the even-better to compete with the bit-better.

Upstream flow capacity currently available on or near the borders of Gaza is sufficient to serve the nutritional needs of residents. There have been two literally fatal strategic problems:

First, volumes discharged through planned bottlenecks — now chokepoints — have been constantly constrained by a wide-array of security-related frictions (please see this January 21 post for more detail and here for even more).

Second, distribution velocity from discharge points into neighborhoods has been repeatedly suppressed by recurring disruptions.

Here is how these disruptions are characterized in LogCluster’s February 26 update of their Gaza Concept of Operations.

Movement restrictions and safe humanitarian access within Gaza conflict-affected areas due to ongoing military operations, complex deconfliction processes and sporadic authorizations to operate convoys, general insecurity, damaged roads, overcrowded areas are impeding the deliveries of humanitarian assistance to affected populations… Electricity blackouts and disruption of mobile networks in Gaza have led to disruptions of communications impacting the ability of humanitarian partners to coordinate and undertake interventions.

It is not yet clear that the proposed maritime channel can avoid or effectively mitigate these two very stubborn sources of friction. Some see this update on Forward from the Sea as one way to “flood the zone” (here and here). If so, the flood gates that have been kept so tight at Rafah must not reappear in Cyprus or at the anticipated Gaza pier (Mulberry Harbor?). From what I hear — but cannot confirm — this maritime play is specifically seen as an end-run around this particular constraint. I hope so.

Suppressed distribution velocity will be much more difficult to avoid (here and here). The current combination of real physics and real fear ought not be discounted. As previously noted, serving profound need justifies profound risk-taking (here and here). But discounting or neglecting such risk is counterproductive. If impossible to avoid, how can these risks be transferred or reduced to facilitate achieving a workable level of acceptable risk?

When first proposing this idea, Cyprus named it after Amalthea (tender goddess). In ancient Greek mythology this was the goat-related foster mother of Zeus, who protected the divine child from his father (who was convinced he had successfully eaten the infant). My favorite aspect of this myth is Amalthea’s recruiting fully armed youthful male dancers (Korybantes) to noisily distract the murderous father from his vulnerable offspring. To not merely move around food, but to actually feed hungry people will require creativity, courage, and a good share of artful cunning as well.

+++

March 9 Response: Some readers are surprised by my affirmative stance regarding Amalthea. I understand; as late as New Year’s Day I might have critiqued this ambitious effort as a strategic distraction. I hope my affirmation these sixty-some days later does not neglect the ambivalences involved. I am very concerned that the two strategic problems identified above will be inherited by Amalthea.

A crucial principle of Supply Chain Resilience is to recognize our systemic dependence on preexisting capacity and flow capabilities. Here is how I explained this in a December 9 post:

Supply Chain Resilience acknowledges that contemporary high volume, high velocity flows of essential human resources serving large populations cannot be replaced, even by the most robust and best-organized relief operations. The only effective and timely way to serve large numbers of survivors is rapid restoration and adaptation of preexisting flows. The current situation in Gaza may be the exception that proves the rule. For sixteen years a huge, dense population has depended on robust, well-organized “relief” operations. Sixteen years of relief operations should have signaled an unsustainable situation requiring fundamental reform. But in the very present crisis, this humanitarian supply chain is the only “preexisting capacity” that has the irreplaceable ability to serve survivors.

So… in December and well into January I pushed for higher volume flows through channels that preexisted October 7. I pushed for innovative velocity enhancements inside Gaza to overcome profound challenges of last-mile distribution in an active war zone. I was encouraged by the mid-December reopening of the Karem Shalom crossing and related steps by WFP-LogCluster, PRC, OCHA, and many other public and private entities to deliver food to hungry people despite extreme duress.

Since mid-January it has been increasingly clear that inbound volumes continue to be insufficient and velocity — both speed and targeting — is deeply degraded. In too many places flow has simply stopped. Preexisting capacity persists. There is plenty of volume within thirty miles of Rafah. But only small volumes are being discharged into Gaza and the trickle entering at Rafah is not moving much farther north.

The sources of these impediments are, it now seems to me, innate to the reality of war (Der Krieg nicht bloss ein politischer Akt, sondern ein wahres politisches Instrument ist, eine Fortsetzung des politischen Verkhers, ein Durchführen desselben mit andern Mitteln (Clausewitz). “War is not merely an act of policy but a true political instrument, a continuation of political intercourse, carried on with other means.”) Many — including Jordan, Qatar, EU, France, US, and UK — have attempted to reverse these impediments. So far these efforts have failed. Evidence is available for the deeply rooted sources of failure. Here and here are two resonant, even tragic, examples.

There are many who continue to work to reverse the causes of these stubborn impediments. I absolutely wish them well. For the 2 million-plus people of Gaza and the flow of preexisting capacity, an authentic and sustained ceasefire would profoundly help.

But I have concluded that given ongoing probability, chance, and friction (as Clausewitz can be translated), both flow and the hungry people of Gaza are essentially being held hostage to a Waiting-for-Godot-Ceasefire. Zweck, Ziel, und Mittel (purpose, objective, and means) have been subordinated to achieving the ceasefire. There has been too little creative, context-specific adaptation to fulfill purposes in our current reality. Rather than adapting our means to the current context, there has been an over-dependence on crafting a new context friendly to preferred means.

While welcoming a ceasefire, until then we need to adapt our means to the innate reality of war. I have affirmed Amalthea not only for the prospect of additional means for achieving the purpose of feeding hungry people, but even more as signal and encouragement for further, faster adaptation of any available means.

March 10 Update:

Times of Israel: How US Military Plans to Build Floating Dock for Urgently Needed Aid

New York Times: US Military enters New Phase with Gaza Aid Operations (more)

DeutscheWelle: US Sends Ship for Gaza Aid Pier (more and more)

Financial Times: Starvation Stalks Children of Northern Gaza

International Committee of the Red Cross: Statement by the ICRC President

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation: US Aid Policy on Gaza “Absurd“

March 11 Update: The BBC reports on several aspects of the Amalthea Initiative and related efforts to increase flows into Gaza. CENTCOM has released visuals of US Army assets that will be involved in building the “temporary pier” off Gaza. The Financial Times has published a concise round-up of issues and actions being taken, including, “The effects of lower levels of aid delivery have been compounded as each day’s shipments fail to compensate for previous shortfalls and the accumulated damage of the war. Most hard-hit are the estimated 300,000 residents of north Gaza who stayed as the area bore the brunt of the initial Israeli ground offensive… For north Gaza alone, 300 aid trucks per day were needed… UN and US officials said this month that a genuine solution would require “flooding” Gaza with aid, not only to help suffering Gazans but to undercut the black market. That would improve security for aid convoys by removing one incentive for looting.”

March 13 Update:

The BBC reports on How the US military plans to construct a pier and get food into Gaza

Reuters reports on US, allies eye commercial maritime option for Gaza aid

The Associated Press reports on four more US Army boats depart for Eastern Mediterranean

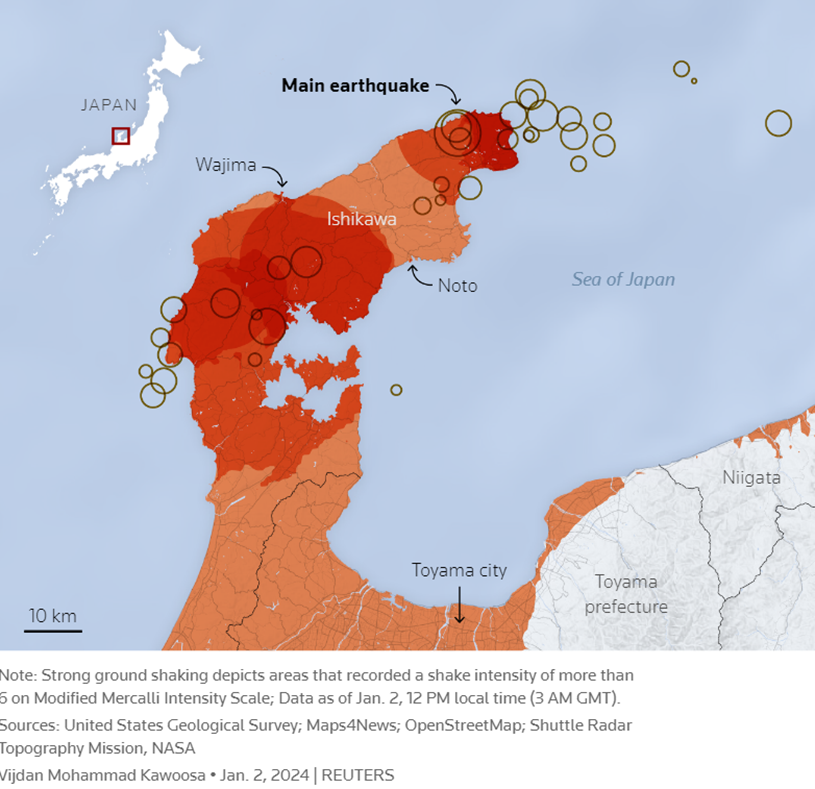

March 15 Update: Relocating more than 1 million residents of Gaza now in and near Rafah to “Humanitarian Islands” is being discussed. The BBC reports, “Moving more than half of Gaza’s population from Rafah to the centre of the strip would take time, potentially weeks… The central part of the strip where Israel proposes to relocate them has been badly damaged by repeated ground and air attacks.” (More and more and more.) Initial reactions to this (long predicted) proposal by those currently delivering humanitarian aid to desperate people crowded in and around Rafah is understandable. “Apocalyptic,” is a common response and, no doubt, accurate description of such a horrific process and its outcomes. A long-term ceasefire remains the preferred solution — and would certainly be preferable for hungry, traumatized residents of Gaza. A thought-exercise: If we were reasonably confident that seismic activity would soon prompt an earthquake and tsunami focused on Rafah, there would be a shared urgency to relocate residents away from the impact. The relocation process and outcome would almost certainly be apocalyptic, but a utilitarian ethic would motivate collaboration and action. Instead of fictional seismic activity, the people of Gaza are threatened by current and escalating military activity. An appropriate ethical response to a natural calamity is widely perceived as immoral complicity with evil (more and more and more and much more could be linked…).

March 16 Response: A reader asks about the potential of Gaza “clan” networks providing a preexisting channel for decentralized distribution of food and other essential flows. I have been asking the same question. I hear ambivalent answers… which given the complex context is not surprising. Below are a few starter links. From a supply chain perspective much depends on flow volume and sustained velocity. If the so-called “flood-the-zone” strategy can be achieved, then the clans — and many other informal connections — should be able to enhance flow velocity to peripheral sources of demand. But the less abundant any high-value flow (the more possible it is to exclude flow in any time/space) the more likely clan leadership will compete, impede flows, and deploy flow-influence to maximize other influence.

Times of Israel (more and more and more)

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace February 2024

International Crisis Group 2007 Study

March 23 Update:

Lots of activity over the last week, but not much substantive change that I can recognize. Below is an update on trucks being discharged into Gaza (more). The Guardian has published a helpful overview of flow impediments (NYT too… nothing new for regular readers). The effort continues to involve preexisting social/family groups (clans) to distribute food (here and here). Work to open a maritime channel has begun. An international conference meeting in Cyprus considered options for increasing volumes and velocity (here and here and here). The Foreign Minister of Cyprus emphasized, ““We have to remember there are limitations in terms of the reception and distribution and the whole point is not to just stockpile aid here but about a quick turnaround so we are as efficient as possible.” The prospects for such efficiency remain elusive. Many continue to insist that the choice is limited to a sustained ceasefire or mass starvation (here and here).

March 24 Update: Quoting the UN Chief, Reuters headlines, “Only effective way to ramp up Gaza aid is by road…” (more and more and more).