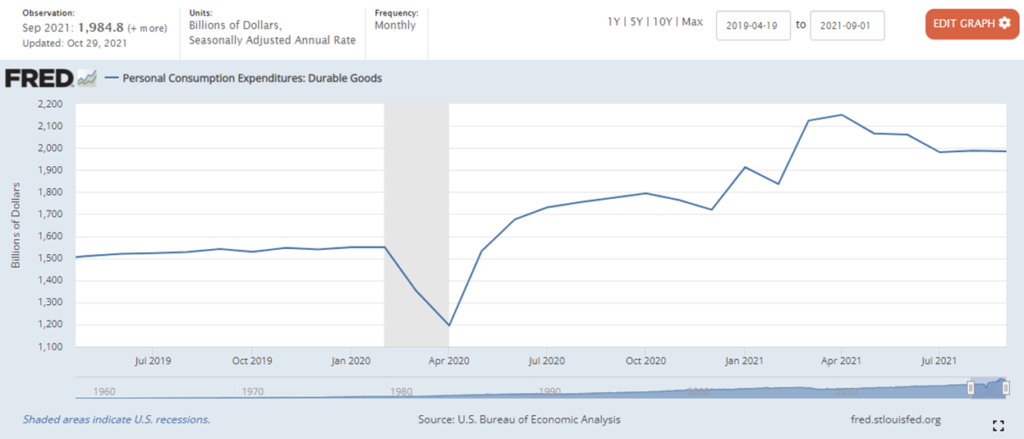

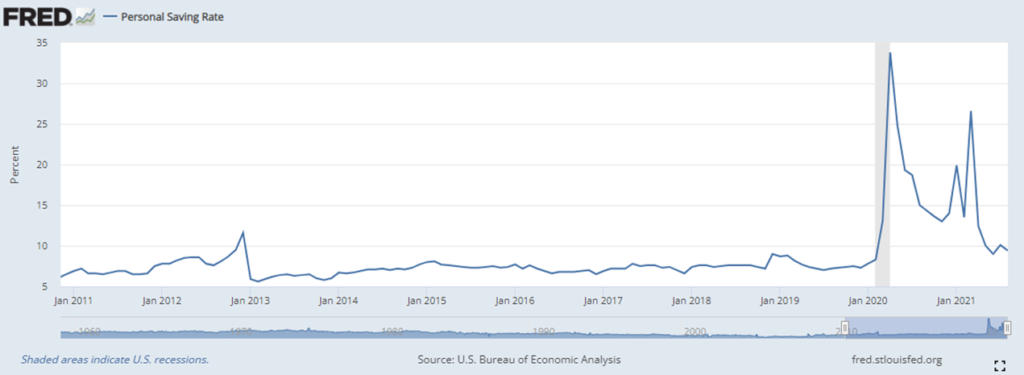

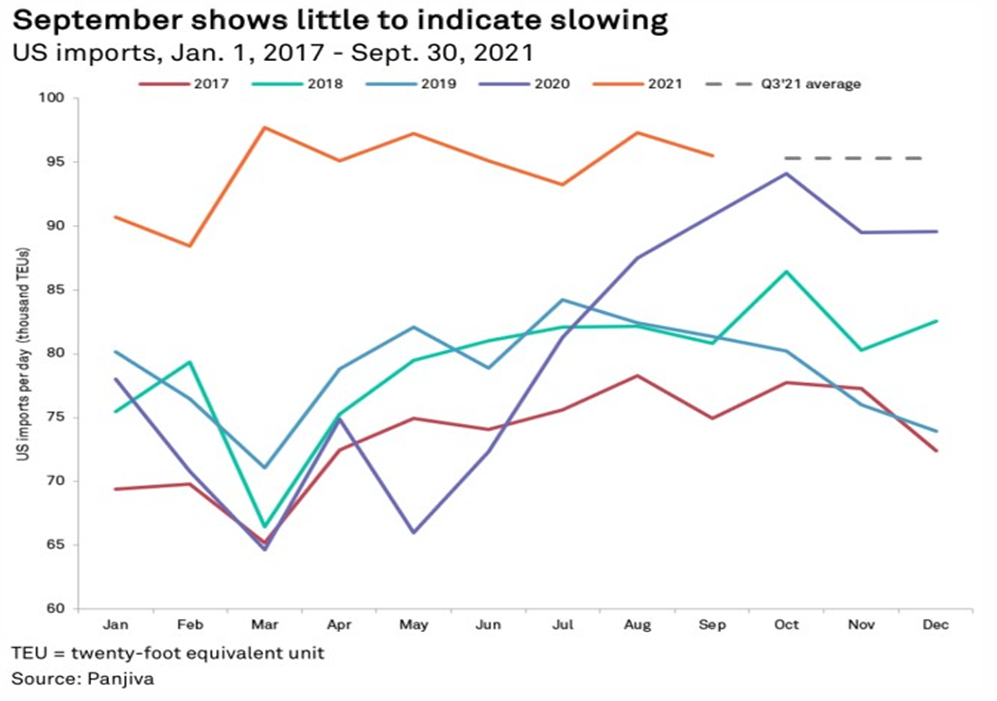

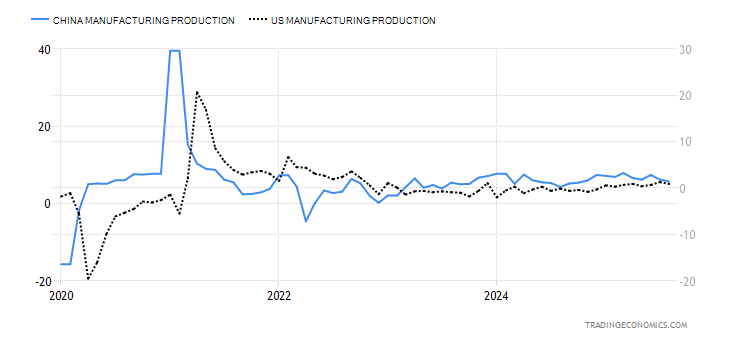

I will stipulate again — as I have here and here and here — that the root cause of recent port congestion has been extraordinary consumer demand. There is also a pig-in-the-python effect associated with delays in East Asia. And… these two factors have been very effective stress-tests for the intricate work of every global port — most dramatically the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Today Bloomberg has done nice work summarizing these interdependent intricacies in an online piece headlined: Every Step in the Global Supply Chain is Going Wrong — All at Once.

As also noted, moving more volume than ever before does not suggest everything is going wrong… and I perceive real progress in the last three weeks with increased velocity and reduced volatility. But this stress-test has certainly unveiled plenty of opportunities for future improvement.