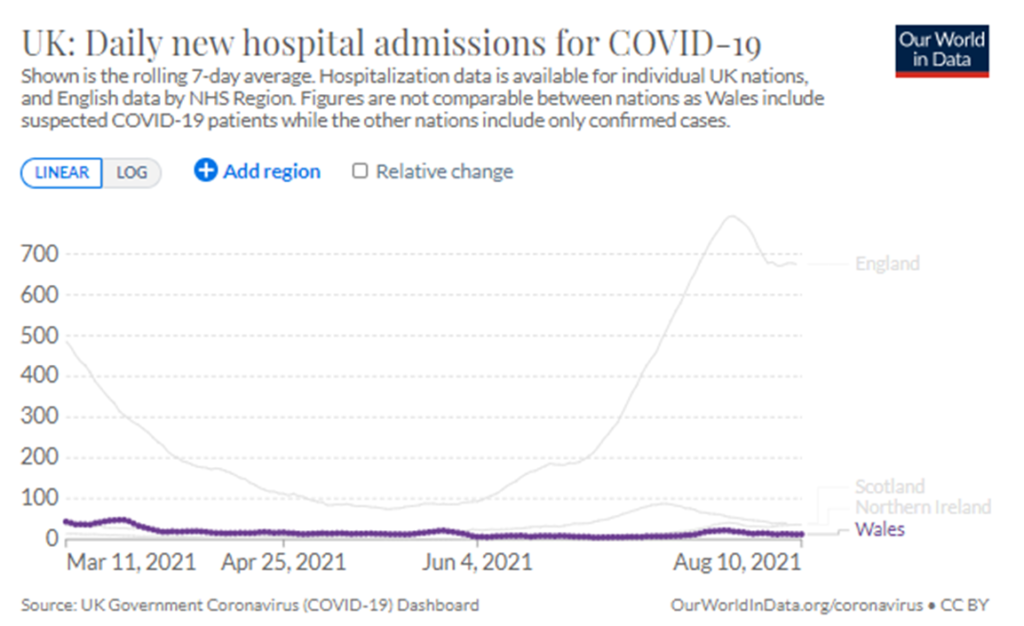

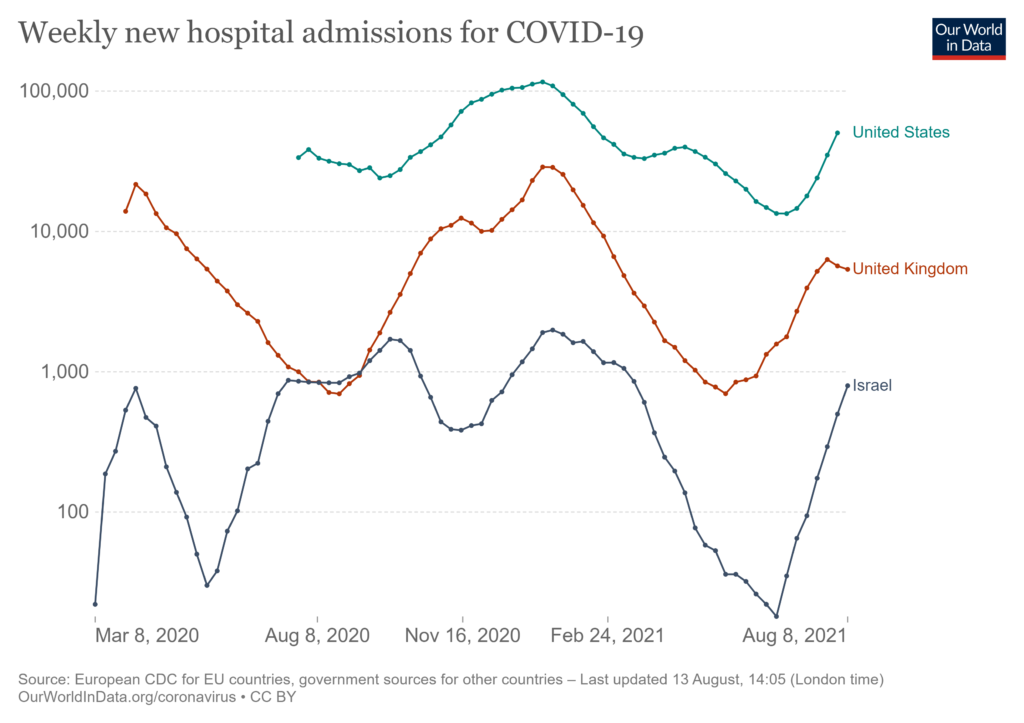

Since mid-July the number of new confirmed cases of covid in the United Kingdom has fallen from above 50,000 per day to about 20,000 per day.

According to The Financial Times:

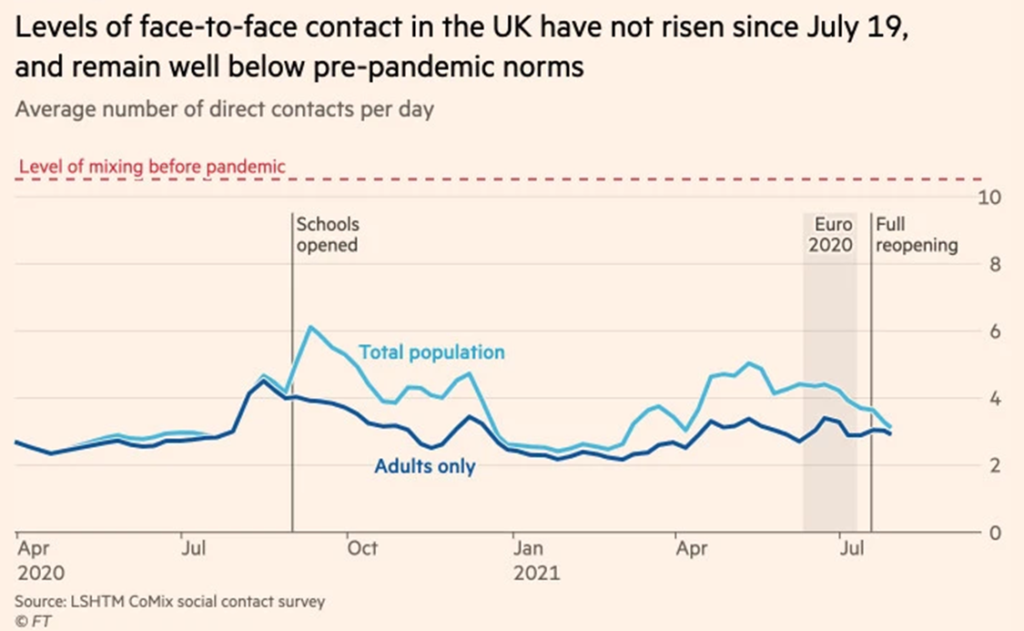

In the week before the government lifted most remaining coronavirus restrictions in England on July 19, the average person was in close contact with 3.7 individuals a day, according to the CoMix survey of more than 5,000 people in England carried out by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

The CoMix Survey does not inspire enormous confidence as a data source. But even if the precise person-count is off, if the trend is correct this clearly would contribute to mitigating circulation of covid.

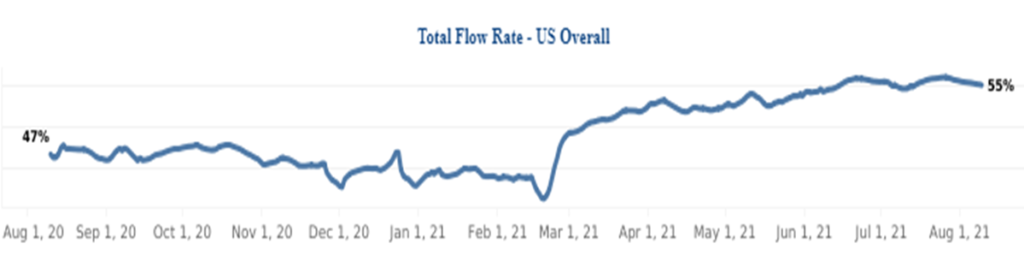

I would have even less confidence in a similar survey of US residents. The roughly analogous indicator that I watch is cell phone mobility. According to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, in late July overall US mobility was only six percent below pre-pandemic “typical” mobility. Below is the mobility trend generated by Cuebiq’s data analysis methodology. Gregarious behavior opens all sorts of opportunities — and risks.