The contending narratives are fundamentally different.

A headline from summery Johannesburg (and its region): As Omicron advances, SA sees limited severe disease (more)

A headline from wintery London (and its region): Significant increase in omicron hospitalisations expected

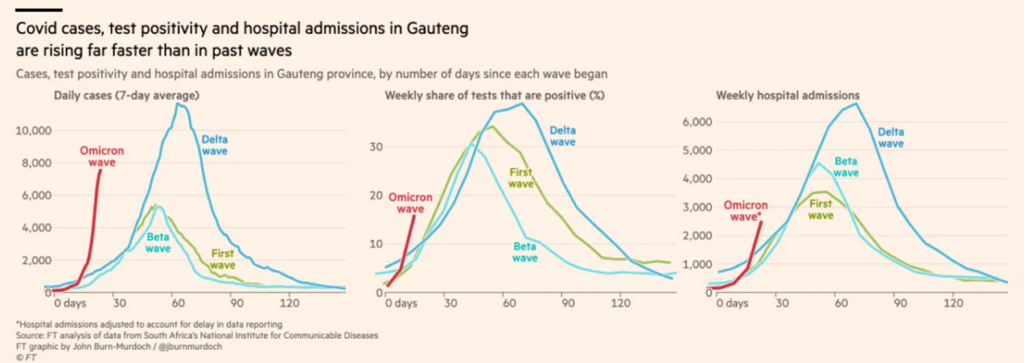

Omicron is now largely confirmed as the most contagious version yet of Sars-CoV-2.

There is also accumulating evidence that omicron is very effective at evading prior immunity — resulting either from previous infections or vaccination. So, reinfections and so-called break-through infections will be tough to avoid.

What remains less clear is the severity (aka virulence) of omicron. What percentage of infections will result in covid requiring medical care and, especially, hospital care? (Projections by University of Texas at Austin COVID-19 Modelling Consortium)

The first large-scale study of omicron cases in South Africa was released yesterday (December 14). One summary of the findings:

Vaccine effectiveness: The two-dose Pfizer-BioNTech vaccination provides 70% protection against severe complications of COVID-19 requiring hospitalisation, and 33% protection against COVID-19 infection, during the current Omicron wave.

Reinfection risk: For individuals who have had COVID-19 previously, the risk of reinfection with Omicron is significantly higher, relative to prior variants.

Severity: The risk of hospital admission among adults diagnosed with COVID-19 is 29% lower for the Omicron variant infection compared to infections involving the D614G mutation in South Africa’s first wave in mid-2020, after adjusting for vaccination status

Children: Despite very low absolute incidence, preliminary data suggests that children have a 20% higher risk of hospital admission in Omicron-led fourth wave in South Africa, relative to the D614G-led first wave.

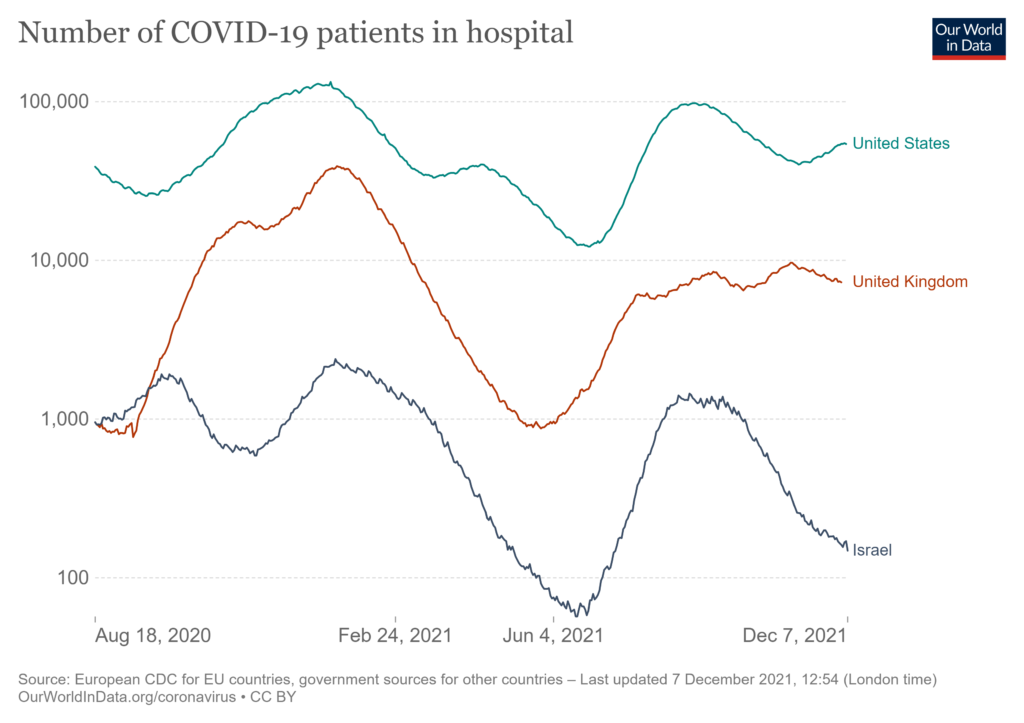

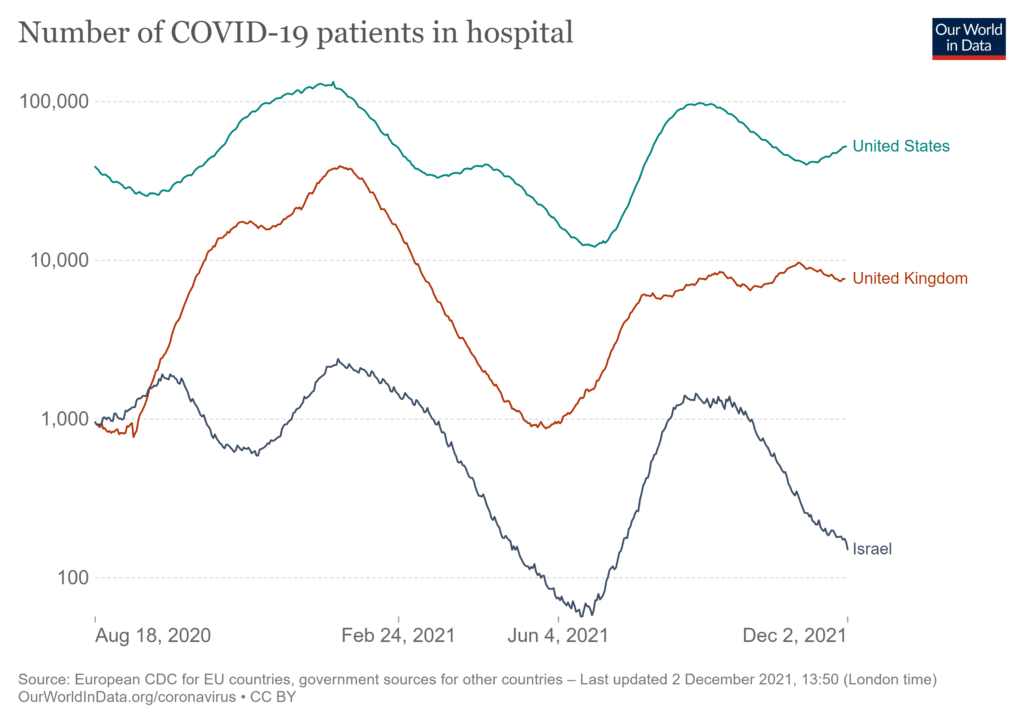

While the narratives contrast, current data are coherent. In both South Africa and the United Kingdom confirmed cases of omicron are skyrocketing. Hospitalizations are not — yet? — surging in either nation.

But the UK government estimates that by now about 200,000 residents per day are being infected with omicron. Some credible projections suggest that with high booster effectiveness plus high immune escape (consistent with current observations) there will be over 300,000 omicron related hospitalizations in England (alone) between December 1, 2021 and April 30, 2022, peaking sometime in January. There are about 6000 critical care beds in Britain’s National Health System out of a total 100,000-plus hospital beds. For prior variants, the median UK hospital stay for covid has been seven days, but this average has ranged between 10 and 15 days during high-admission waves. The median length-of-stay for those admitted to intensive care units is even higher. Pre-pandemic bed use was typically over 90 percent.

There is no obvious reason that the United Kingdom’s encounter with omicron should be unusually difficult. Given the status of vaccination and therapeutics, the UK ought to be better off than many others.

We cannot yet know how this tale of two cities will end. The original began with, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.”

Sounds about right.