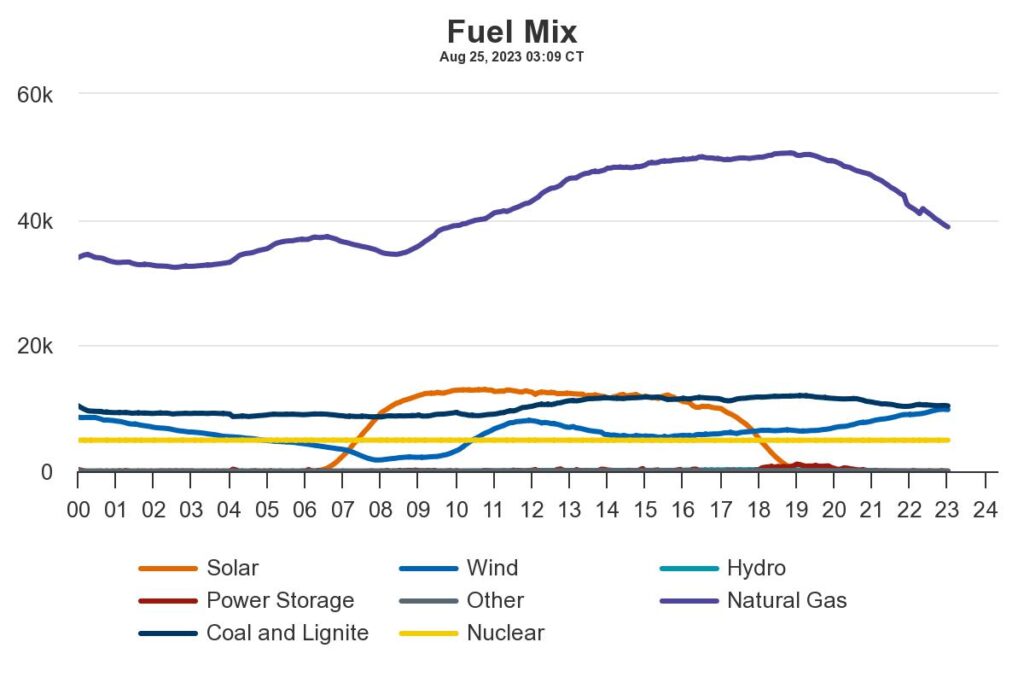

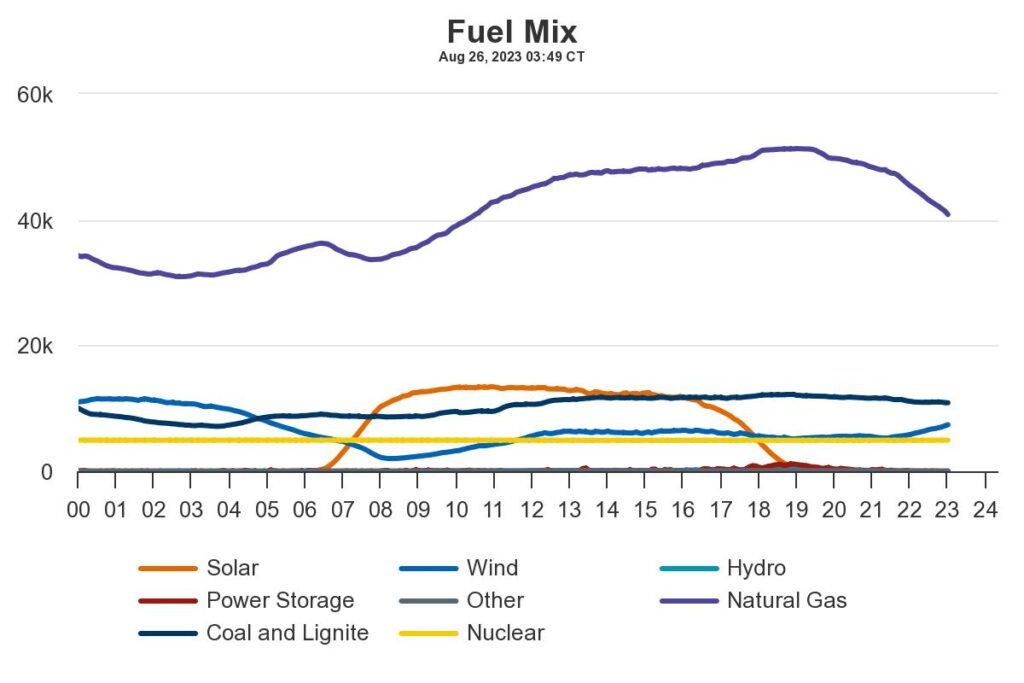

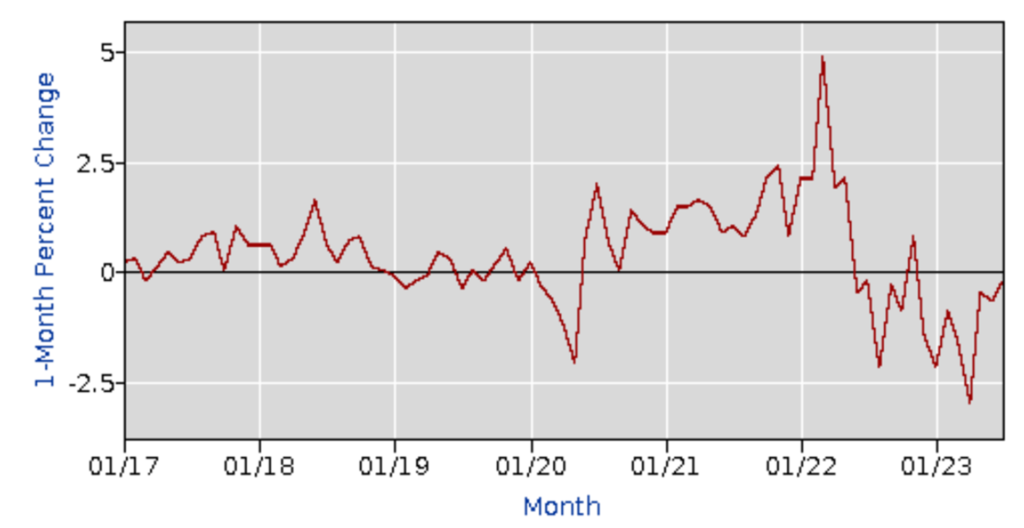

Below are multi-year slopes for the Consumer Price Index for food. Here is the complete Bureau of Labor Statistics’ explanation of what happened in August:

The food index rose 0.2 percent in August, as it did in the previous month. The index for food at home increased 0.2 percent over the month, after rising 0.3 percent in July. The six major grocery store food group indexes were split over the month, with three increases and three decreases. The index for meats, poultry, fish, and eggs rose 0.8 percent in August as the index for pork increased 2.2 percent. The index for other food at home increased 0.2 percent over the month and the index for cereals and bakery products rose 0.5 percent. The index for dairy and related products decreased 0.4 percent in August after increasing 0.5 percent in July. The fruit and vegetables index declined 0.2 percent over the month, as did the nonalcoholic beverages index. The food away from home index rose 0.3 percent in August. The index for limited service meals rose 0.3 percent over the month, and the index for full service meals increased 0.2 percent. The food at home index rose 3.0 percent over the last 12 months. The index for cereals and bakery products rose 6.0 percent over the 12 months ending in August. The meats, poultry, fish, and eggs index was unchanged over the year. The remaining major grocery store food groups posted increases ranging from 0.3 percent (dairy and related products) to 4.8 percent (nonalcoholic beverages). The index for food away from home rose 6.5 percent over the last year. The index for limited service meals rose 6.7 percent over the last 12 months, and the index for full service meals rose 5.2 percent over the same period.

During most of 2020, 2021 and the first half of 2022 demand and supply for food (and much more) was totally discombobulated. Today’s nominal prices are often much higher than pre-pandemic and a serious gap emerged between price increases and wage increases. This was a source of considerable demand volatility to which supply chains were hard-pressed to adapt. During this period, food became much less affordable for the two least affluent economic quintiles.

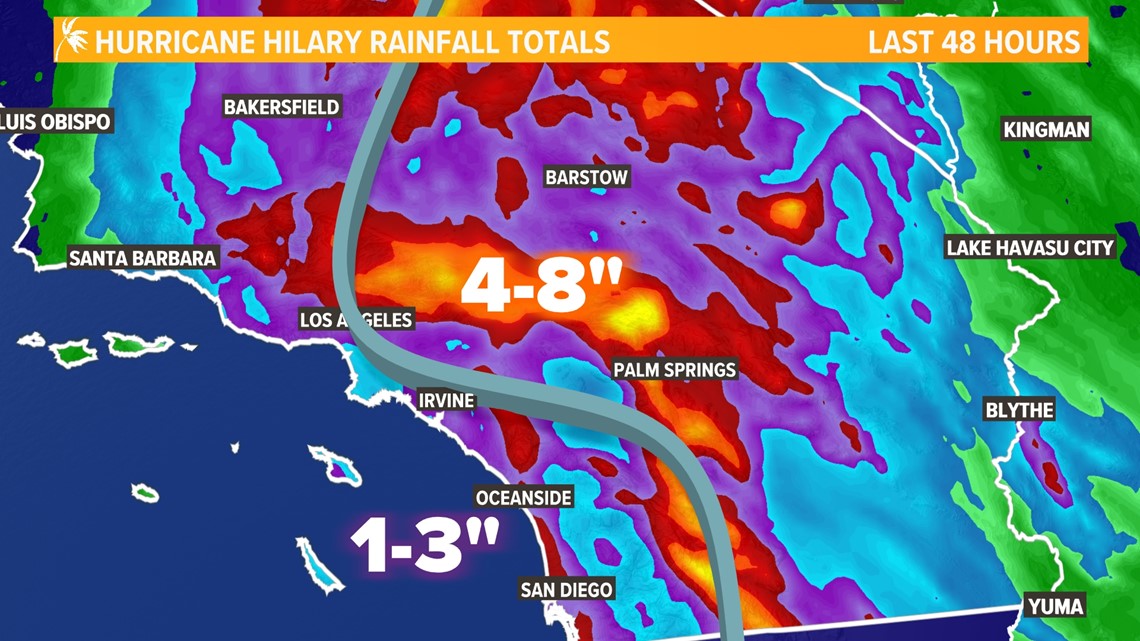

But from a Supply Chain Resilience perspective, I perceive that since the beginning of 2023 the CPI for food — especially Food At Home — has been modest and healthy. This sort of nominal growth supports supply capacity and, given this year’s inflation-adjusted wage increases, are within reach of most households. The August CPI indicates some serious inflationary pressures (especially related to fuel and more), but 2023 grocery pull patterns are, so-far, well-matched to sustainable push capacity.

+++

September 14 Update: According to today’s Census Bureau report on August retail sales, seasonally adjusted sales at grocery stores increased from $73,644 million in July to $73,933 million in August (both are nominal, non-inflation adjusted figures). Given the population size, amounts of money involved, and inflation, this is about as flat as I would ever expect to see. Here’s the Fed’s related chart. Year-Over-Year there was much more spending growth in Food-Away-From-Home (8.5 percent compared to 2.1 percent), but the recent rate of growth in FAFH appears to be slowing as well.