Every variant of SARS-CoV-2 has produced mild symptoms in most of those infected. By now many of us — perhaps most of us (who do not live in New Zealand or Tonga) — have been infected but have remained asymptomatic (or barely symptomatic) and don’t even recognize our encounter with covid. But for two to three percent of those infected, results have been much more difficult, even life-ending.

There is accumulating evidence that — so far — the earliest encounters with omicron produce modest morbidity — especially when people are vaccinated. Here (again) is the most recent study out of South Africa. Here are two just-released studies from the United Kingdom, one from the University of Edinburgh and a second from Imperial College (London). I cannot yet find original source material for an analysis just completed of omicron cases in Denmark, but here is a helpful overview of three of these four reports (including Denmark’s) in this morning’s Financial Times.

In most places for most people individual risk of omicron causing serious covid is no worse or less than previously. People who are vaccinated have reduced risk. People who are boosted have very low risk of experiencing serious disease.

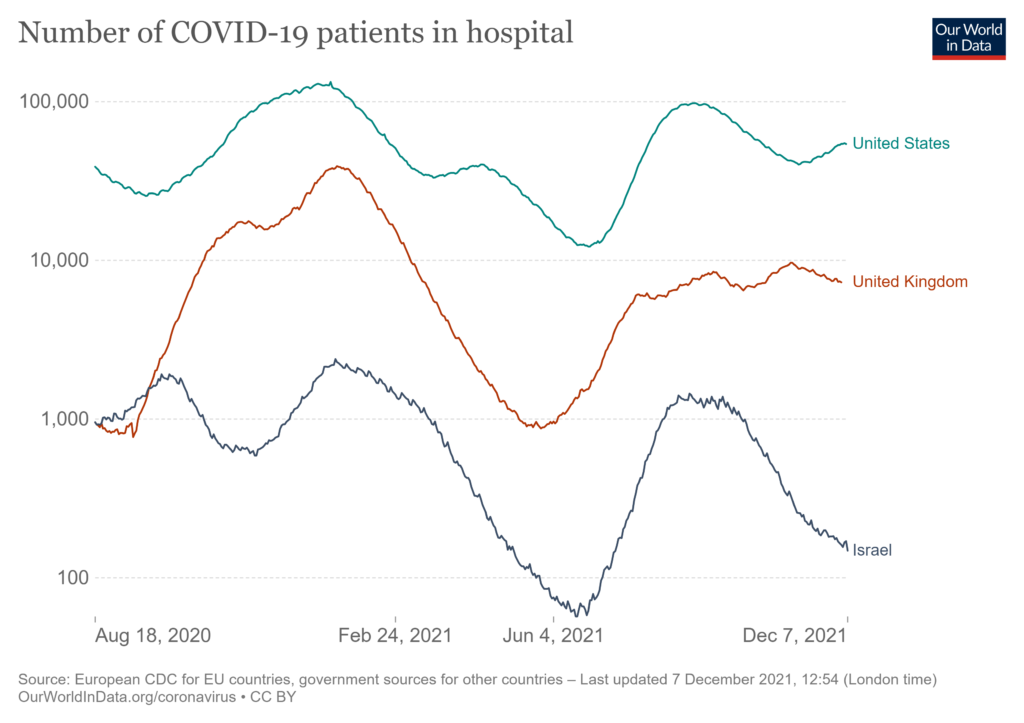

But omicron is very contagious, the most contagious variant yet. Omicron has also demonstrated a rather amazing ability to re-infect those with prior immunity (natural or vaccinated). Even if the hospitalization rate for omicron is the same or a bit less than prior variants, omicron’s transmission rate could push the health care system over the edge. A two percent hospitalization rate for 300 million cases will cause six-times the hospitalizations of two percent for 50 million.

Which is just a long way of saying, epidemics are less about individual risk than population risk. I am well over sixty, but otherwise my individual risk profile for serious disease is modest. I wear a mask, keep my distance, and minimize circulation to protect others from me. Mass vaccination does have individual benefits, but mass vaccination is especially important to manage risks for the most vulnerable among us. I am — all of us are — potential hosts and mutation factories for viruses. We will continue thus until we have suppressed SARS-CoV-2 worldwide. In most cases, our personal risk to this virus is negligible. But to reduce the risk to the most vulnerable — and those who are called upon to care for the most vulnerable — I want to do what I can.

There are obviously epidemiological and ethical implications here. I also perceive supply chain implications. Supply capacity is almost always the outcome of expensive long-term investments… for example in clinical facilities, pharmaceutical innovation… manufacturing… distributing, extensive professional education, and much, much more. Certainly, we want to build-in buffers for variation in demand. But there is seldom an affordable, reasonable way to develop supply capacity for a sudden doubling or more of well-established large-scale demand. So, I want to do my part to reduce demand on an already stressed system.