We are increasingly confident that omicron is highly contagious. From South Africa to Denmark the velocity of transmission has been a bit stunning. As early as today we may have the results of initial virological studies of omicron virulence (aka severity). As widely reported, so far the epidemiological outcomes of omicron are characterized by modest morbidity. It will take another week or more to reasonably estimate the efficacy of current vaccines vis-a-vis this new variant.

While we wait to learn more it can be worthwhile thinking self-critically about scenarios and options.

Today, let me be optimistic and assume that omicron is no-more (and maybe even less) virulent than the the Delta variant. Call me Pollyanna, but I will also assume that vaccines approved for use in the United States continue to be effective in significantly reducing the risk of serious disease and death (related). In other words, most Americans — even vaccinated Americans — may eventually be infected by omicron, but when vaccinated most of us (let’s say 80 percent of those vaccinated and boosted) will not experience health consequences requiring hospitalization.

If these very optimistic scenario elements were confirmed in the next two or three weeks, it would be one of the best Christmas presents possible.

And… roughly forty percent of 330 million Americans are not vaccinated. Less than 15 percent of US residents have received booster shots. But, continuing to be optimistic (and to make the math easier), for this scenario I will project a potential demand pool for US covid-related health care of only about 100 million. So far, of those infected with prior versions of covid, only about two-percent require hospitalization…

Hmmm… suddenly our scenario is less optimistic.

And… when I consider there are roughly four billion people on the planet who have not been vaccinated, the ongoing potential for transmission, reinfection, mutation, and further reinfection seriously challenges my optimism. Especially while we remain uncertain of omicron’s virulence and related vaccine efficacy, I can continue to generate various Panglossian justifications (“the best of all possible worlds”) (more). But more troublesome projections are equally or more credible.

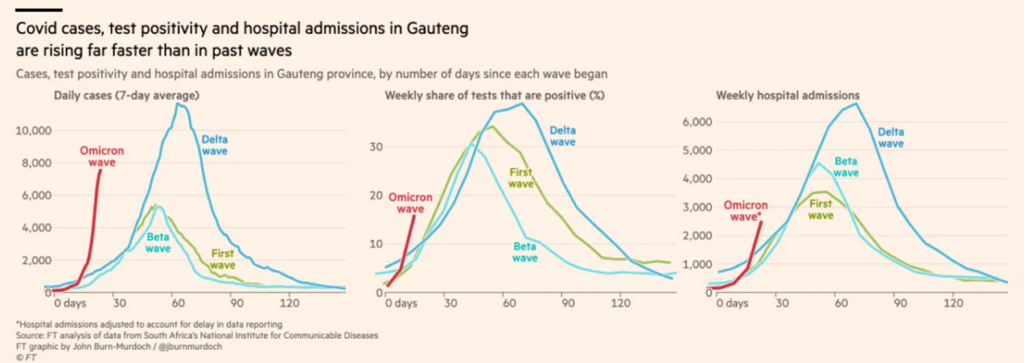

If you can, please read today’s helpful analysis in the Financial Times: Omicron’s less severe cases prompt cautious optimism in South Africa. The chart below is extracted from this story. Given my preceding efforts to be optimistic, I view the outcomes below with considerable concern.