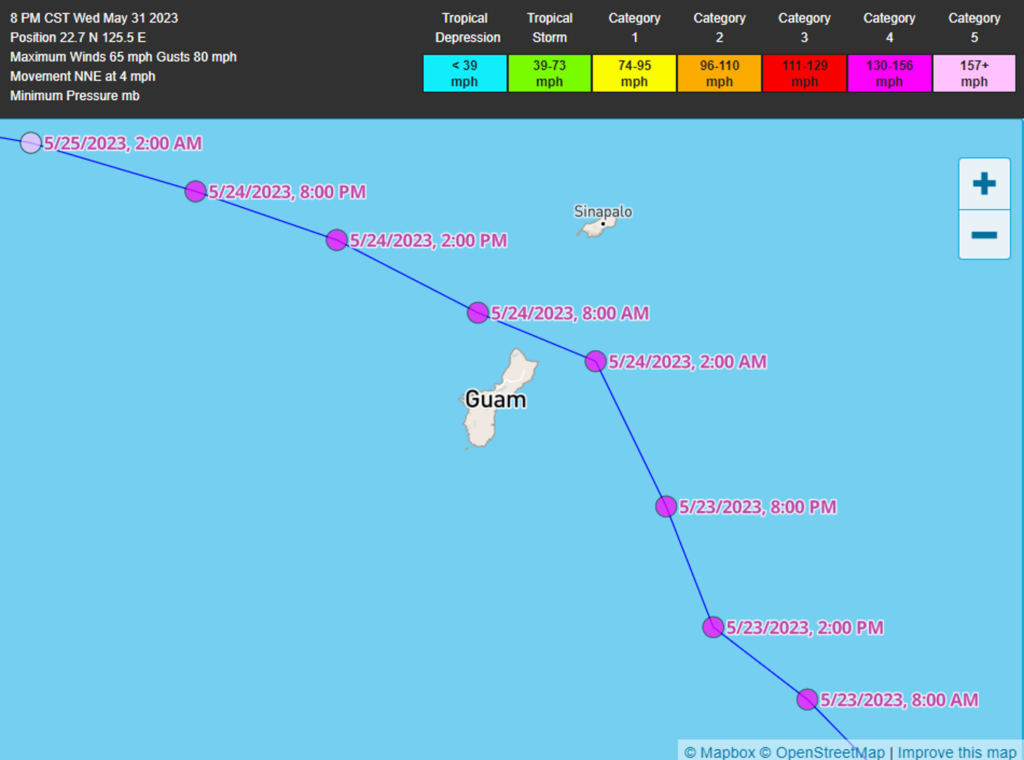

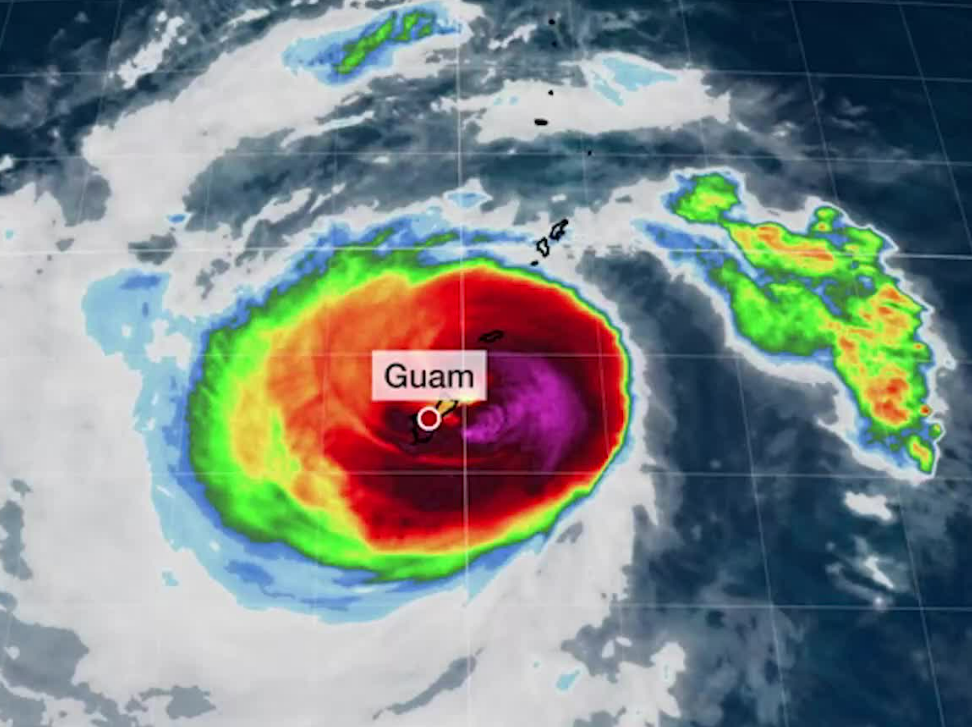

Last week a very high-end typhoon — similar to a CAT4 to 5 hurricane — impacted Guam, a US territory in the Western Pacific. Guam is roughly 30 miles long. It is one mile to almost nine miles wide (roughly the same total area as Columbus, Ohio). About 170,000 people reside on the island. Guam is located almost 4000 miles west of Hawaii, over 6000 miles west of Los Angeles, and 1600 miles south of Tokyo and east of Manila.

Typhoon Mawar approached Guam from the southeast with sustained winds of about 150 mph (see maps below). Matson’s container ship, Maunawili (departed Long Beach on May 11) was scheduled to dock on Tuesday but maintained a safe distance until the typhoon passed. (Matson service to Guam from Long Beach generally takes 13 to 14 days.) As the typhoon approached, three US flag cargo vessels were scheduled to arrive at Guam before the end of the month:

Maunawili (Matson, US Flag) scheduled GUAM ETA 2023-05-23 15:00 LT (UTC +11) DELAYED

Herodote (CMA CGM, US Flag) scheduled GUAM ETA 2023-05-26 12:30 LT (UTC +11)

Manoa (Matson, US flag ) scheduled GUAM ETA 2023-05-30 17:00 LT (UTC +11)

There were also two non-US flag fuel tankers scheduled to arrive Guam: LPG Tanker Epic St. Kitts (ETA 5/26) and Oil Products Tanker Topaz Express (ETA: 5/29).

This line-up suggests ordinary flow (volume and velocity) providing food and other crucial freight to residents.

On Wednesday, May 24 Mawar’s large eye skirted Guam’s northern tip basically battering the island — especially the northside — for over 24 hours. The Guam Daily Post reported the gradual loss of grid power and public water services over the day and into the night. By Wednesday afternoon all but 1000 customers had lost power. Boil Water Advisories were released.

Strong winds and heavy rain continued on Thursday morning impeding response and recovery actions (more). By Thursday afternoon winds had receded enough that some grocery and fuel outlets reopened, all reported doing cash-only transactions because of the loss of grid power, telecommunications, and point-of-sale (POS) technology. Travel was complicated by debris, but most roads were passable.

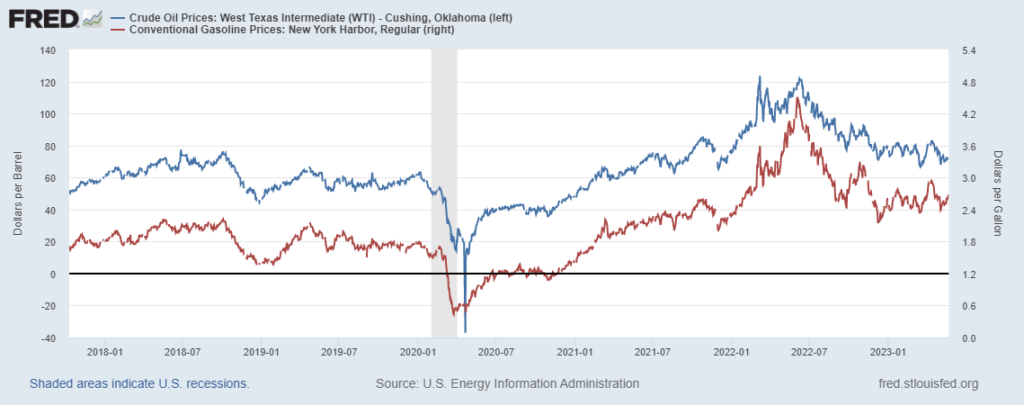

Thursday afternoon saw the start of sustained grid and water system restoration. Guam Power Authority (GPA) “critical restoration priorities include hospitals, critical water well and wastewater facilities, critical infrastructure facilities, schools/designated shelters, public safety/health facilities, and ports of entry.” With the grid down, use of private generators increased demand for fuel, but many fuel retail stations remained closed because of lack of grid power, lack of staff, and inability to operate digital POS transaction devices. Telecommunications restoration started. The airport was capable of handling limited emergency cargo flights.

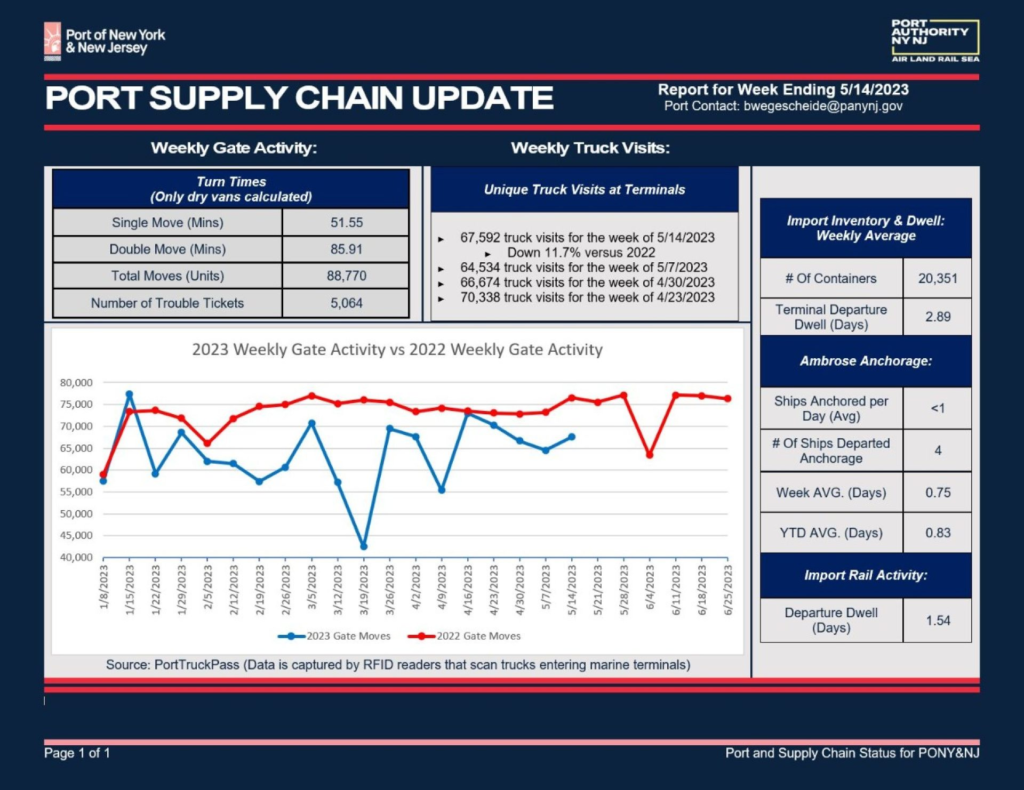

By Friday, May 26 the Joint Information Center reported less than five percent of grid customers were reconnected. About 40 percent of electrical substations had been reenergized. The Guam Water Authority reported that the water system was operating “normally” but at 50 percent capacity. Boil Water Notices continued. According to the JIC, “The Port Authority of Guam (PAG) has received clearance from the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) to begin major recovery efforts dockside. PAG weathered Typhoon Mawar with visible damage to Piers F3, F4, F5 and F6, particularly the Bull Rail. Portions of the Fender System also are damaged or broken off. The storm also caused damage to the Agat and Agana Marinas. PAG continues assessments on their wharves, docks, cranes, and facilities…”

On Friday and Saturday long lines were reported at the comparatively few operating retail fuel stations and strong demand exceeded tanker truck refilling capacity (more and more). There was plenty of fuel at the terminal/racks, but tankers available to distribute the fuel could not keep up with demand. [Please see June 4 update below maps.] Repairs continued at the port where damaged cranes were a particular problem.

On Sunday, May 28 according to the Joint Information Center, water authority crews worked to restore non-operating wells. More than 30 percent of wells needed power or minor repairs. Almost one-fifth of wells required pump motor replacements. The JIC also reported that by Sunday afternoon:

- 16.2% of the System Load (Customer Demand) has been restored.

- 65.4% of GPA’s Substation Energization has been restored.

- 27.0% of GPA’s feeders/ circuits have been energized/restored.

The Guam Daily Post reported continued strong demand — and mile long lines — for fuel. Velocity of demand, especially as a result of FOMO and increased demand to fill private generators remained significantly beyond the velocity of existing distribution capacity. Actual on-island supplies of fuel products remained adequate to fulfill demand.

The port reopened on Sunday and the Maunawili was unloaded. Over 450 containers were discharged. CMA-CGN Herodote also discharged cargo. The Yasa Albatross oil tanker docked. The Topaz Express arrived. Ships scheduled to arrive by May 31 include Matson’s Manoa, the LPG tanker Epic St. Kitts, CMA-CGN Dakar, and the container ship Kota-Ratu. (More.)

The airport reopened for regular flight operations on Monday afternoon.

Ongoing updates are available from the Joint Information Center and ReliefWeb and The Guam Daily Post.

The quick recovery of maritime port operations has been fundamental. Especially with the grid gone and disrupted public water, it has been crucial that food and bottled water flows persist. I am inclined to treat the Maunawili as a leading indicator. The typhoon delayed unloading for 48-plus hours. Recovering port operations required another 48-plus hours. With the port reopened food, fuel, and other flows could resume and catch-up with ordinary volumes and velocity. If anything had caused the port to be unable to resume operations, the population would have become more vulnerable with each passing day.

This is consistent with most contemporary supply chains: when concentrated capacity (the planned bottleneck) survives, supply chains may be delayed and constrained (such as by fuel distribution cycle times) but surviving bottlenecks can support creative and resilient flows. When bottlenecks become time-extended chokepoints, a realistic and well-exercised Plan B better be competently deployed sooner instead of later.

+++

June 4 Update: It is now confirmed by credible folks who should know that some of the fuel racks at the port were inoperable in the days after Mawar’s May 24 transit. I don’t know if these shut-downs were related to loss-of-grid, flooding, mechanical failure or whatever. I have seen only one especially vague written report. We will eventually find out. Disrupted supply plus surging demand equals manifest frustration (and worse). This, too, is a recurring classic of hardest hitting force-on-target events. I visited my first fuel rack the second morning after Superstorm Sandy’s 2012 visit to NYC and nearby. In that case with the grid gone, pumps to fill tanker trucks would not work. There were millions of gallons of refined products still sitting a few feet away, but nary a drop for tanker trucks nor, therefore, for cars or generators. Back then fuel racks (like food distribution nodes) never appeared on priority restoration lists. This remains unusual today. I can, however, report that every fuel rack I have visited along the US Gulf Coast now has an emergency generator to keep the pumps pushing.