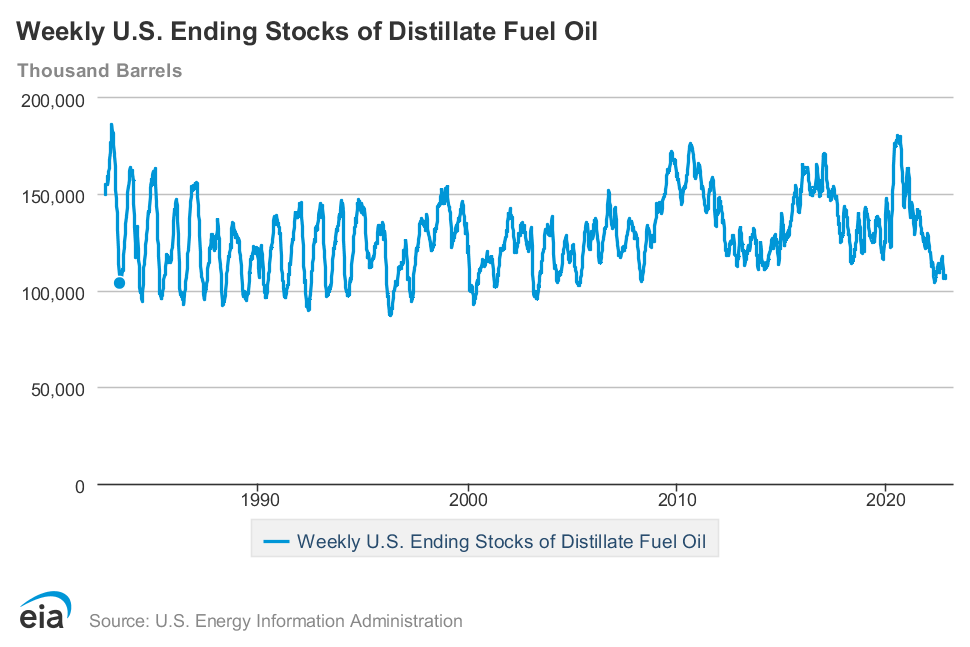

In the United Kingdom eggs are in short supply. Culling flocks due to avian flu has reduced upstream production. There are social and regulatory constraints on imports (more and more). Avian flu has also reduced stocks of broilers and egg laying hens on the continent (France and Netherlands (US too)). Constrained supply and higher production/transportation costs (often energy-related) have caused prices to increase by half since earlier this year, discombobulating demand in a manner that disrupts supply. It is complicated.

This is not, however, as bad as some were predicting last Spring. At that point the scope and scale of the European energy crisis plus drought projections plus the risk of a wider war prompted some plausible worst-case thinking of wide-spread cuts in core food production, processing, and freight movement. Brexit-related frictions were expected to amplify British consequences (as they have).

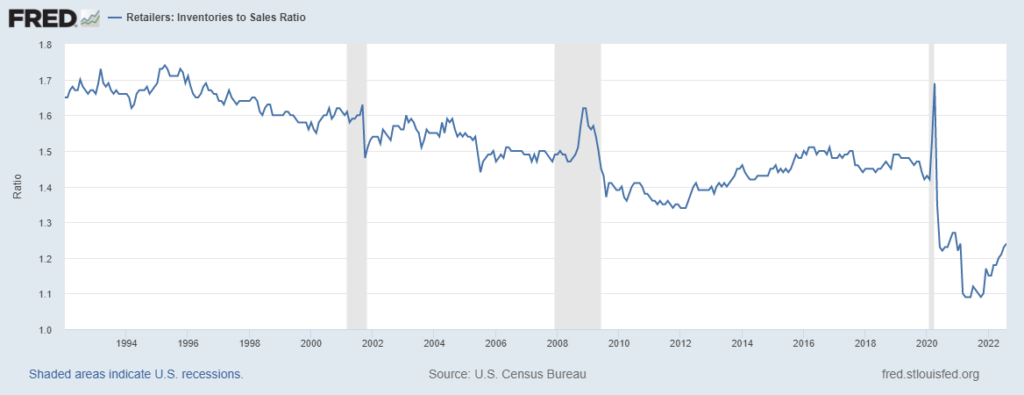

While far from a best case, over the last six months adaptations in European energy flows have achieved higher inventories and much more flexible (effective) velocity than I expected. Agricultural production has been uneven, more costly, and bulk transport often delayed, but European food resources are diverse and imports have been available to fill gaps. Freight players and processors have — so far — demonstrated considerable agility. Volumes have been sufficient to fulfill European food demand in the vast majority of places for the vast majority of products, the vast majority of the time.

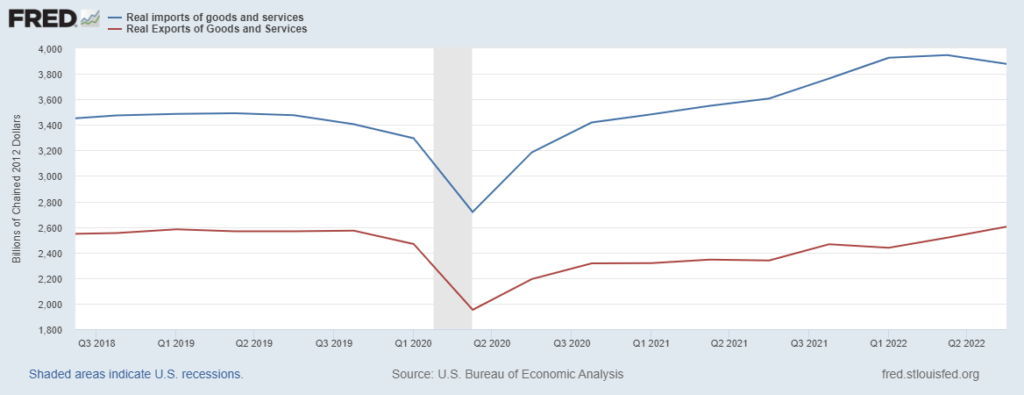

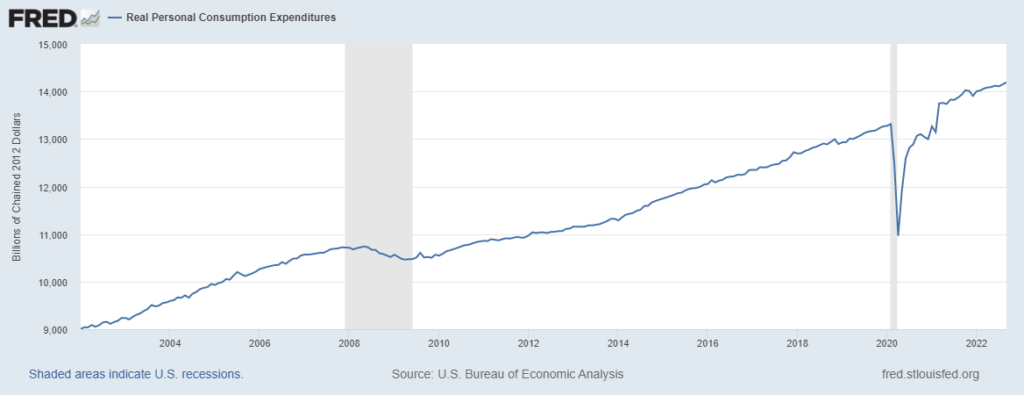

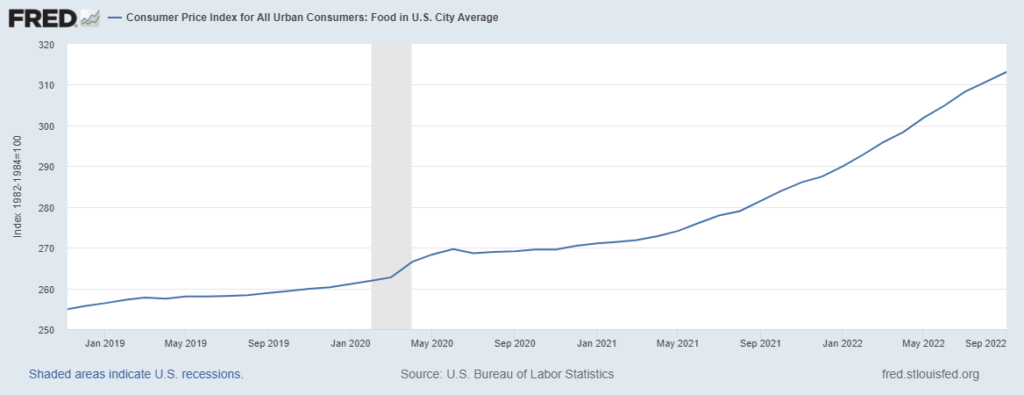

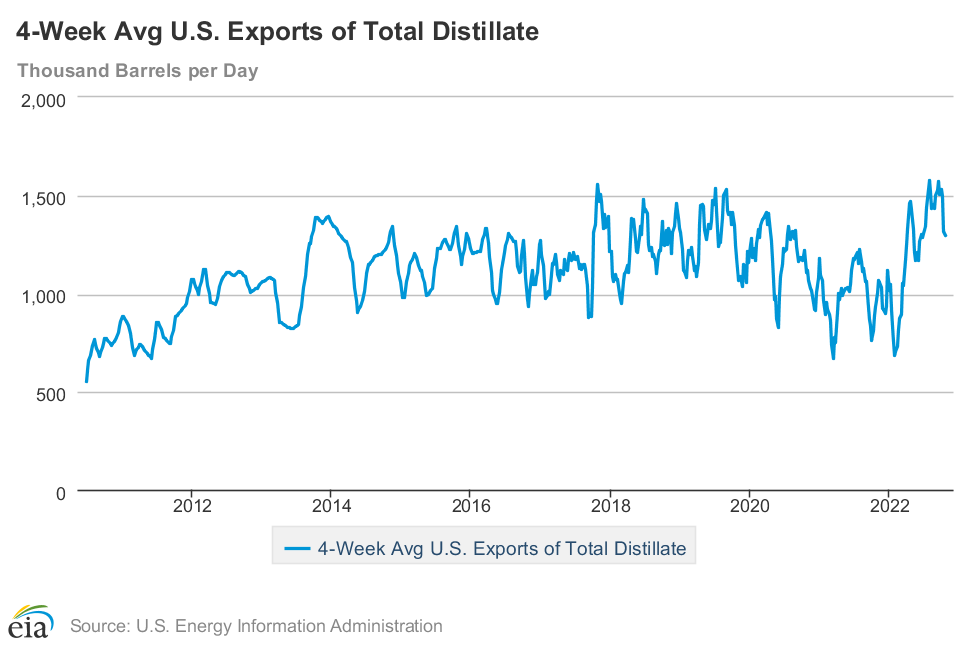

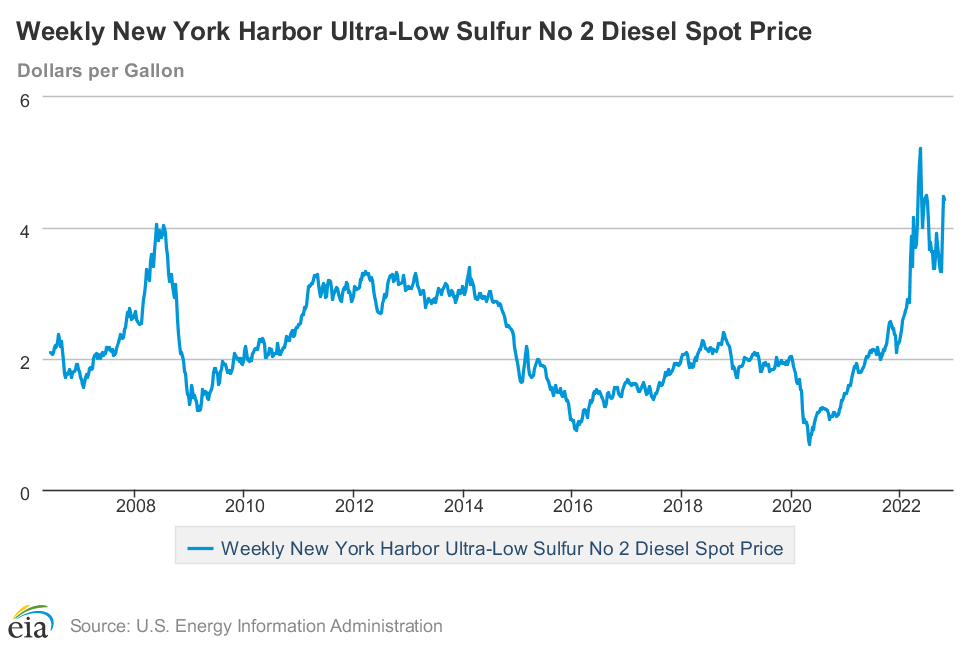

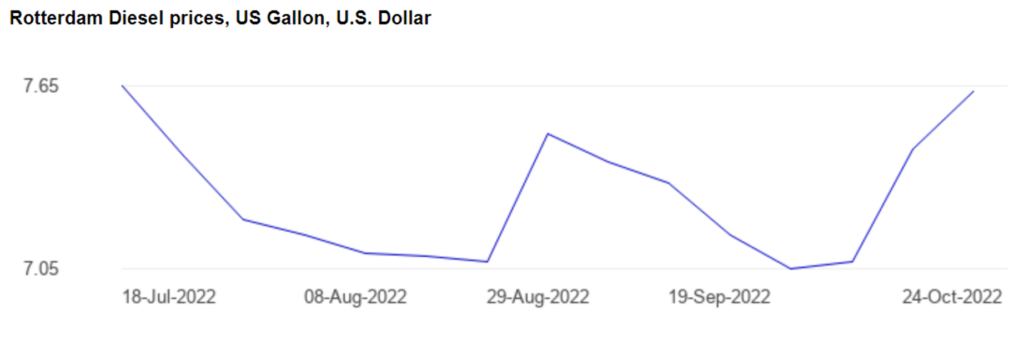

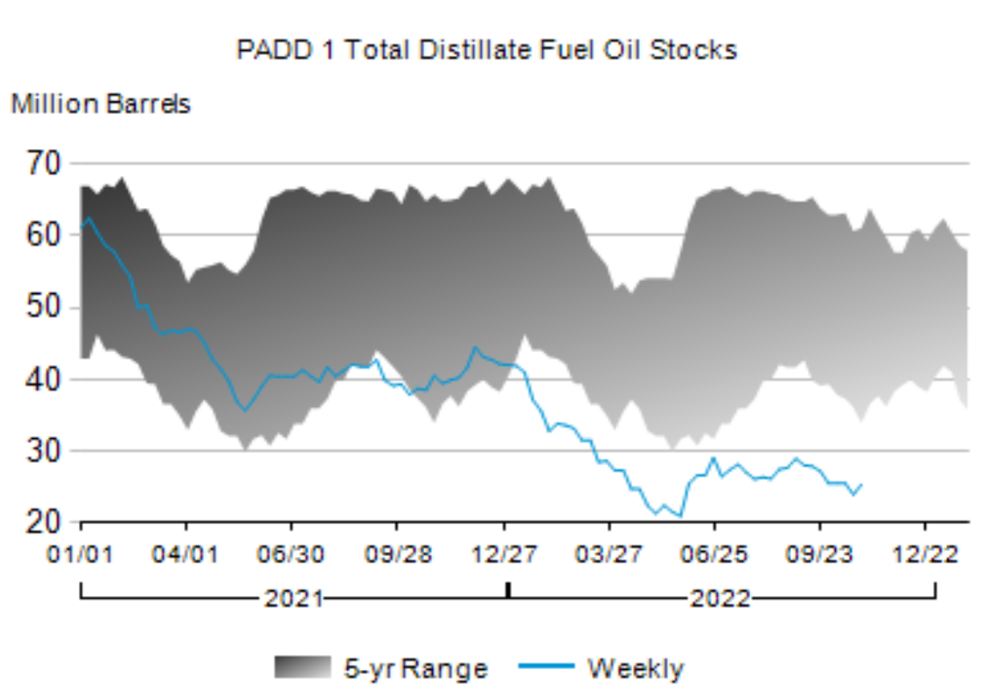

As usual, this success has many sources. But demand pull and open flows have been fundamental. If these two factors had not been available or more seriously constrained, other sources could not have delivered the energy and food needed by 700 million plus Europeans. Spending on energy has soared (here and here and here and here). EU household utility costs are up almost 40 percent compared to decade-plus averages. In October the EU-wide inflation rate for food was over 17 percent (core inflation was just under 6 percent). Through September 2022 LNG imports to the EU already equaled more than the previous full-year record in 2019. During the first half of 2022 total EU food imports increased by one-third. Increased pull has motivated increased push.

+++

In December 2016 I participated in a global consultation on mass care in case of catastrophe — or at least near-catastrophes. The consultation was hosted in Berlin and focused on food flows. One of the principal discoveries was wide-spread lack of understanding related to midstream aspects of the food supply chain. Expertise was readily available for upstream food production, imports, and exports. There was also considerable shared familiarity with consumer-facing retail. But flows in-between were often a mystery.

Nonetheless, after the Berlin consultation I wrote my German hosts, “Given the structure of European food flows and the character of your risk vectors, the only catastrophic potential I recognize is the intentional targeted destruction of war.” This was not a prediction. It was, in fact, supposed to be reassuring.

In February 2019 there was a loosely related Copenhagen consultation on post-Brexit food flows for (mostly) Northern Europe. The lack of midstream awareness persisted, but there was much more sensitivity to how regulatory constraints (e.g., customs processes) can create physical chokepoints. One of our Dutch colleagues noted, “given volumes required, very marginal constraints on flow can have enormous market consequences for volume, velocity and price, spontaneously generating unwanted chokepoints.”

Late this Spring some of the same folks and many new colleagues gathered around Zoom screens to think through European food flows for the soon to arrive war-torn winter. Despite (or perhaps because of) the earlier work, there was considerable anxiety. But by late September when we gathered face-to-face there was much more confidence. Our Dutch colleague was now hosting. His closing remarks included, “perhaps we now better understand the limitations of our understanding and share a deeper appreciation for the ‘invisible hand’ of market pricing to prioritize what is really needed.”

It remains a hypothesis requiring more testing — I can still imagine proving the null hypothesis. We are still a long ways from a proven theory. But there is accumulating evidence for a principle of good practice that gives priority to facilitating pull.